MusicWeb International

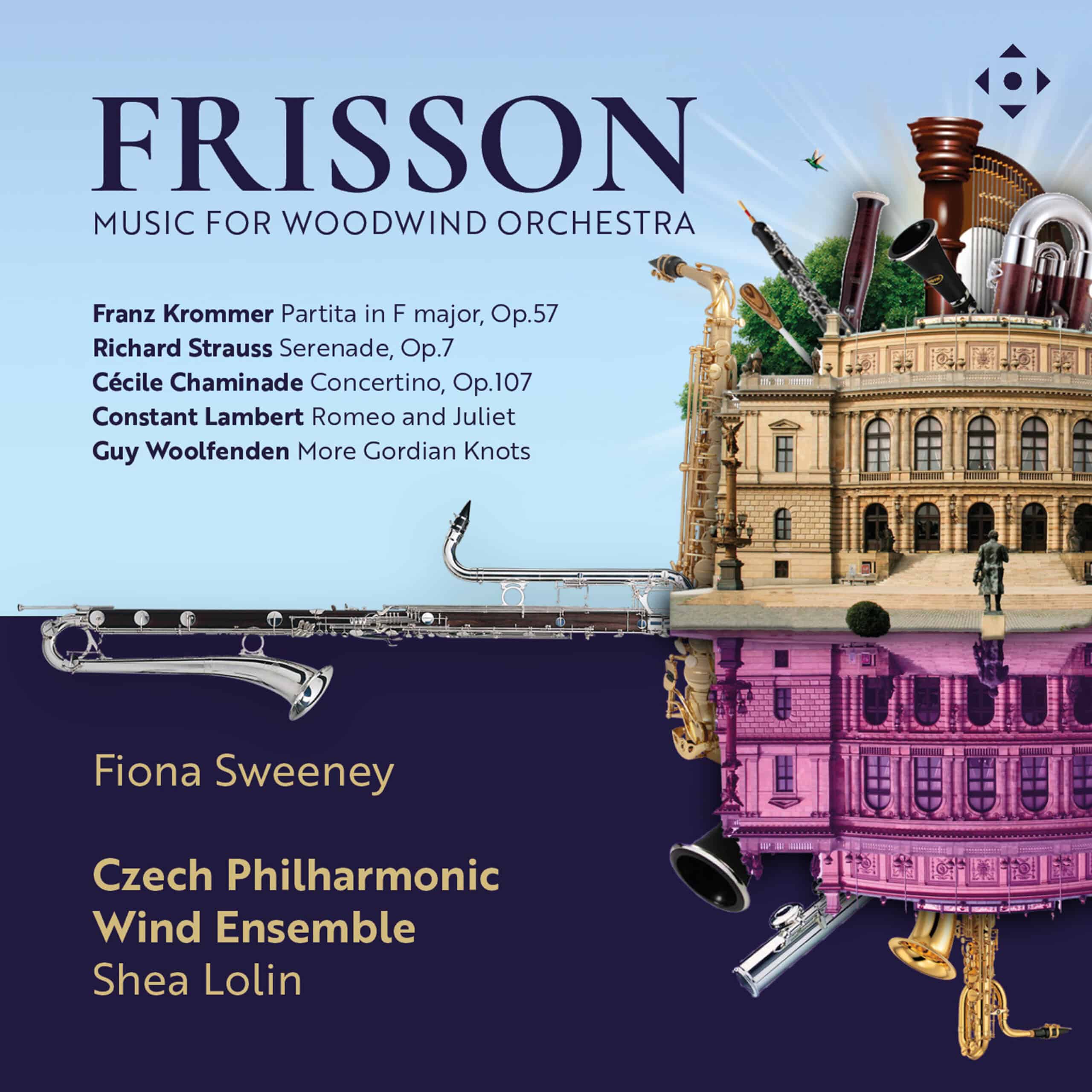

This is a thoroughly enjoyable disc. The brainchild – indeed passion – of conductor/arranger Shea Lolin, it is presented as a modern expansion of the 18th Century Harmoniemusik ensemble. In a preface to the liner, Lolin briefly explains the historical development of this small woodwind group from a sextet of players in the court of Emperor Joseph II, expanding to eight, then ten players, adding flutes, contrabassoon and combining clarinets with oboes. As Lolin writes, the result was a richer fuller timbre and the repertoire for such ensembles ballooned by the 1830s to include over 10,000 works. To quote Lolin with regard to this new disc; “My aim is to showcase the woodwind orchestra as a contemporary evolution of Harmoniemusik, challenging the misconception that it is merely a scaled-down version of a full wind orchestra”.

To achieve this, the works performed here are all new arrangements by Lolin of scores that existed for different ensembles – the exception is Guy Woolfenden’s More Gordian Knots. The liner lists 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 6 clarinets (although one is marked as “Woolfenden only”), bass clarinet, contrabass clarinet, 2 alto saxophones, tenor saxophone, baritone saxophone, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon and harp (Chaminade only). Most notable here is the absence of any horns which were an early addition to the original Harmoniemusik ensemble. It is not clear whether this complete line-up play in every work but the collective sound is every bit as sonorous and rich as you would hope. Add to that more than a hint of the unmistakable ‘woodiness’ that Czech/Slovak and Central European orchestras and their wind sections used to have as their trademark sound and the result is a delight.

Franz Krommer’s Octet-Partita opens the disc. Although his dates are close to Beethoven’s Krommer’s musical style harks back to Mozart. From the opening bars the rich and full sound of the Czech Philharmonic Wind Ensemble impresses – I really like the discreet presence of the saxophones (in lieu of the horns, perhaps?) warming the middle textures while the bass instruments give a powerful foundation to the timbral mix. Solos are played with real elegance and sensitivity. The recording was made in the famous Dvořák Hall of the Rudolfinum in Prague. Engineers can sometimes struggle in this acoustic with full or large orchestras but here Producer Mikel Toms and Engineer Vitek Kral have produced genuinely excellent results with plenty of detail but a pleasingly warm and supportive overall acoustic. The closing Alla polacca embodies the good-natured spirit of the work and the collaborative skill of the playing. I do not know the original work at all but to my inexpert (not a woodwind player!) ear this transcription sounds effective, idiomatic and thoroughly enjoyable to play.

Richard Strauss’ early Serenade Op.7 is a much more familiar work. It was scored for pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinet and bassoons with four horns and a contra-bassoon completing the line-up. In its own right this new performance/version is very beautiful with wonderfully unaffected phrasing and immaculate ensemble playing. Again, the saxophones deputise for the horns – I would be lying to say I do not miss them but the ear soon adjusts and enjoys the music-making rather than fretting over the scoring. The inclusion of Cécile Chaminade’s Flute Concertino Op.107 is perhaps rather unexpected but delightful. In the liner Lolin does not explain why he chose to arrange this piece but that said it receives another very appealing performance from the Czech players accompanying British flautist Fiona Sweeney. Again, the engineering is very successful at allowing the solo part prominence within the all-wind sound picture with sounding inflated. The smaller scale of the whole ensemble brings the sound stage closer to the listener than is often the case in the full orchestral version with Sweeney proving to be an ideal combination of lyrical and virtuosic as required.

Constant Lambert was one of those rare musicians of ferocious talent across a wide range of musical disciplines. As the liner notes, his enduring legacy has proved to be his major role in the creation of a world class British national ballet company – the Vic-Wells ballet becoming Sadler’s Wells Ballet which ultimately spawned the Royal Ballet Company. Lolin’s choice of five movements from his ballet Romeo and Juliet is again as inspired as it is unexpected. It is still astonishing to consider that this ballet was commissioned by Diaghilev for his world-famous Ballets Russes when Lambert was barely twenty years old! Along with a Lord Berners score these were the only two works written for Diaghilev by British composers. The story of the initial meeting bears brief repetition. Lambert went along with William Walton to meet the impresario as moral/practical support as Walton was in line for a Ballet Russes commission. Walton’s piano playing of his proposed work was so clumsy and his natural reticence left Diaghilev distinctly underwhelmed in direct comparison to the articulate and literally brilliant Lambert – who got the commission instead. Lolin has followed Lambert’s own suggestion extracting a five-movement suite from the complete (albeit brief) ballet. The style of the original score translates very well to wind orchestra both in the manner of the original neo-baroque titles; Sinfonia, Siciliana, Sonatina, Adagietto and Finale but also the musical idiom itself. Lambert blends textural clarity with jazz-like syncopations and piquant harmony all of which sound particularly effective in this ensemble. The fourth movement Death of Juliet is a striking contrast with plaintive quite austere solo lines again beautifully poised and phrased. It is in music like this that the sheer talent of Lambert – even at such a young age – is fully apparent. As a composer if his enduring fame still rests on the novelty of The Rio Grande, which to my ear has dated quite badly, the music performed here shows how effective and fluent a composer he could be. I imagine this was completely unknown to the Czech musicians before the sessions but they clearly relish the buoyant textures and bustling energy of the arrangement here. I would go as far to say that I think this is quite possibly more effective in this version that the full orchestral original.

Guy Woolfenden’s More Gordian Knots that completes the programme was inspired by a study of Henry Purcell’s theatre music specifically his score for The Gordian Knot Unty’d (1691). Woolfenden wrote this score in 2010 and as mentioned before, this is the only work presented here not arranged by Shea Lolin. The three movements are Air, Chaconne and Jig and are a modern reworking of the Purcell original by Woolfenden – as an aside the same Purcell work was arranged by Holst. The tempo of Woolfenden’s Air is distinctly stately compared to what might be considered a more ‘historically aware’ approach but this does allow some of the new scrunchier harmonies and textures to register effectively. The closing Jig is witty and light-hearted conclusion to the disc, although I do wonder if the Lambert selection might have made for a more telling culmination of this genuinely effective programme.

This is a very well presented, well played, beautifully engineered and skilfully arranged programme. Quite why “Frisson” was chosen as the umbrella title escapes me, but that is my only very minor quibble. It is a recital well worth investigating by the simply curious or woodwind aficionados alike.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

![🎧 Listen now to the @purcellsingers' first single from their upcoming album, #ASpotlessRose! ➡️ listn.fm/aspotlessrose [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/642752592_1424641949105789_8815810652567824072_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=106&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=aY1NGfNpOoYQ7kNvwG97Dxr&_nc_oc=Adn5peUdrqmvdK4ifJdU7OimsPpAZrc-0vhiYJQzsqC8GCkIfBMzP-pVJFoHmPMPMaA&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=1-kTd01oea1X-rpO1Oaedw&_nc_tpa=Q5bMBQG4Migw-I4Ddjz5j5V_0jADm5LQ-qvE4-LkVcT3DIe7tT7ENeVi5LaR4H79cxFX0XiDZHdRn2-Vjg&oh=00_AfwNXW-1EjESLSo_dP_6GmBR5MzkLqLsJKq1TE-hqBZD5g&oe=69B10701)