Fanfare

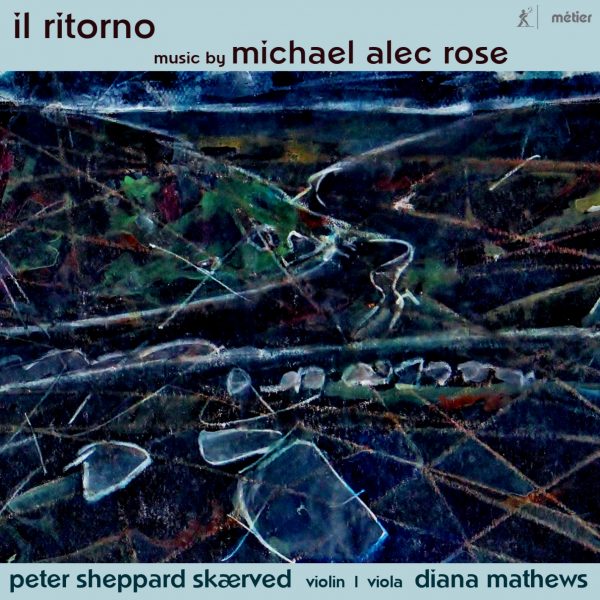

Michael Alec Rose is one of about a dozen composers with the surname Rose in the Fanfare Archive, and a Toccata Classics disc of his music, reviewed by Colin Clarke in 37:3, was issued some years ago by the indefatigable Martin Anderson. Clarke’s positive review included some biographical material, so readers interested in such details may easily consult it. Having not heard that CD or any of Rose’s music elsewhere, I put the present Metier disc into my player with the anticipation of a child about to embark on his first experience on a Ferris wheel, and indeed, Rose’s music provided a most enjoyable ride. The Toccata CD featured works for string quartet, as well as duos for violin with cello or double bass, and the CD in hand continues to explore Rose’s string music presenting a pair of solo violin works and another pair of duos for violin and viola. Also as in the Toccata disc, violinist Peter Sheppard Skaerved is featured. He is a marvelous exponent of the instrument, so I am happy to be¬come acquainted with his artistry, along with that of violist Diana Mathews.

Rose’s musical aesthetic is tonally based, but is far afield from anything resembling traditional functional harmony. The composer has developed his own harmonic language, and I find his musical idiom both innovative and pleasing. The opening work, Unturned Stones, is cast in three movements, the first featuring flurries of figuration, while the second allows both violin and viola to sing their own “songs” in imaginative counterpoint. The tempo picks up once again in the final movement, albeit with greater syncopation than is heard previously, and Rose again demonstrates his mastery of counterpoint in this movement. The piece’s title is drawn from the phrase “to leave no stone unturned,” and the implication is that in this work the composer not only desired to explore the sonic possibilities of the two instruments employed, but to consider epistemologically the dialogue between them. Skaerved and Mathews play together with impeccable precision and skill.

Lasting more than a half hour, Ritorno is the major work in the recital, being a six-movement suite for solo violin, and finding many moods in its movements, “Preamble,” “Bearings,” “Silence,” “Water,” “Stone,” and “Song.” The subtitle of the work is “Perambulation for Solo Violin,” and describes in musical fashion the composer’s peregrinations in Dartmoor, an area of moorland in southern Devon, England. Dartmoor’s scenery, including the exposed granite hilltops known as tors, so profoundly affected Rose upon his initial trip to the region in 1991, that he considers it as a “defining epoch of [his] life.” The program notes, in fact, go into considerable detail about his experiences in this haunting place. He further states that he feels “not so much obsessed by the place, as redeemed by it.” Thus the title of the present work is not intended to convey the idea of returns to some musical idea in the piece (although such do occur), but refers to the composer’s return to Dartmoor at least 17 times since his initial visit. He seems to consider each visit as a kind of homecoming, even imagining that his Jewish ancestors may have smelted tin at the King’s Oven there. How much of this place may be heard in the music may be debatable, but I do perceive a restless quality in the music, and a mysterious element of solitude that whispers something of a place that doesn’t quickly reveal its secrets. Skaerved skillfully brings out these elements as though he had been to Dartmoor himself, which in fact he has on at least two occasions. I do not know if Rose plays the violin himself, but he writes well for the instrument, employing double-stops and pizzicato in idiomatic fashion. Most of the work is slow to moderate in tempo, but the “Water” movement picks up in velocity considerably, and has a few sequences of notes that hearken back to Bach’s Chaconne. A real surprise in this movement comes when the soloist is called upon to sing a few notes. The mystery of the piece reaches its zenith, however, in the penultimate “Stone” movement, in which the violinist plays quick arpeggiated figuration in its highest register pianissimo, and the movement ends with a glissando over a sung low Bb by the violinist.

The two concluding works on the disc are both brief, being each under four minutes in duration. Mornington Caprice is a work inspired by the Frank Auerbach painting, Mornington Crescent – Early Morning. The work is more subdued that what one might normally expect with the title Caprice (especially if one is thinking “Paganini”), but the interplay between the violin and viola in this work is adroitly done. Diaphony for solo violin concludes the recital, and provides a rather lively adventure for the soloist, although it also has interspersed moments of reflection in its episodic construction. The piece was written at the request of Skaerved, who asked simply that it reflect something about Alexander the Great, and it provides a most effective close to this fascinating recital. Both Skaerved and Mathews are masters of their instruments, and apart from the inspired music heard herein, are well worth hearing in their own right. As Shakespeare almost said, the music of Rose, by any other name, would be just as sweet.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

![🎧 Listen now to the @purcellsingers' first single from their upcoming album, #ASpotlessRose! ➡️ listn.fm/aspotlessrose [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/642752592_1424641949105789_8815810652567824072_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=106&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=49FisD1EbHcQ7kNvwGTG_S5&_nc_oc=AdnMCIQHKqf0lhT_TEPyGVlF5eW1j-_3wtRLJQ4iLHwxSt7P-IwIPStoJXelYqvTs20&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=XfbSU8xLC8x2zdiM43sLJg&_nc_tpa=Q5bMBQHfIoib3d4r1e8Gw98O1ogCfed7JUbkQbye9l-B3SYEjq4Z4fCsIaXkO0f2J72Np1eKFN0z34aKtQ&oh=00_Afzstq-RQX2_cF_Dceg7Xj3MqeCf4trEzQDMVzZi8nWNiQ&oe=69B64D01)