The Consort

Terence Charlston is surely one of England’s most modest virtuosi, whose reputation among his fellow musicians is extremely high. Over the last few years he has explored, and offered us recordings of, less familiar repertoire, performing on a range of copies of old instruments, two being clavichords of early design. Terence admits to having been drawn increasingly towards the clavichord, pointing out that it offers subtleties of expression unique among keyboard instruments. This, together with the difficulty involved in playing it well, led it, like the lute in seventeenth-century France, to be considered among the greatest of all instruments. I am reminded of another fine player from a different age: between the two World Wars, Violet Gordon Woodhouse also moved from harpsichord performance to a preference for the clavichord, finally using it almost exclusively for early repertoire.

Charlston’s recording of early – some very early – French music, using a clavichord built by Peter Bavington, to a design based on an illustration from a French treatise by Mersenne dating from the first half of the seventeenth century, was highly praised. Bavington’s clavichord, which had an unusually deep case and several separate bridges, produced an extremely satisfying sound, akin to that of a lute. Considering the date and provenance of that model, it may be at first surprising that the same clavichord did not appear again on this new CD. The historical match, and its soulful and often beautiful sound would arguably have suited the music of Froberger (1616-67) very well, but the repertoire is in fact very different. This CD contains exclusively contrapuntal music from Froberger’s second book of 1649. These pieces, unlike his works inspired by contact with French musicians during a stay in Paris, owe more to his time studying with Frescobaldi in Rome, not long before that master’s death in 1643.

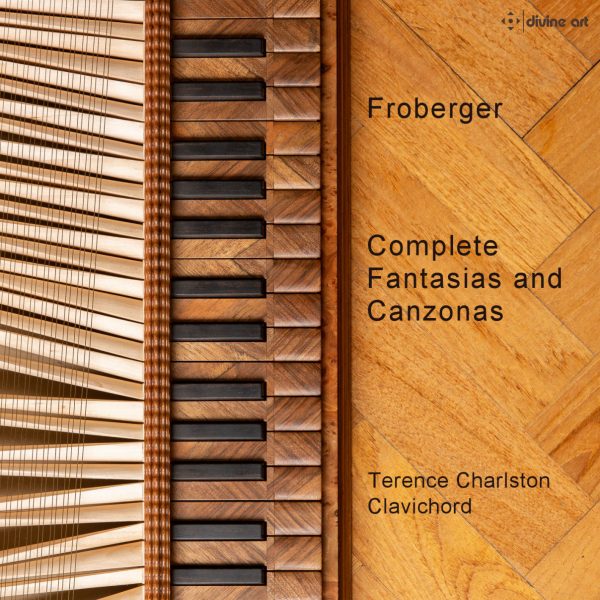

Charlston therefore employs a very different clavichord for this CD. The German maker Andreas Hermert has taken an original unplayable instrument in the Berlin collection and reconstructed it to its original design, omitting later changes (including the fitting of extra treble frets to allow easier articulation). The ‘copy’ is a very handsome instrument, which the maker believes to be from the late seventeenth century – but with ‘features of older building traditions’. The most telling of these may be two triangular cut-offs within the rectangular case, at each rear corner. Possibly a coincidence, and certainly adding elegance, these result in a marked similarity to the plan of the Mersenne clavichord mentioned above.

Apart from this, though, the new instrument (the original is thought to be south-German) is radically different: the case is very shallow; there is a single bridge, which has a possibly unique severe ‘hook’ to the bass end (assuming this is not a whim of the maker). For a fretted clavichord, the case is unusually extended to the right of the keys, reminiscent of less severely fretted instruments by Hubert, around a century later. This allows for particularly long bass strings and a larger than normal soundboard.

The compass is chromatic C to c”’, minus bottom C sharp, although I suspect the tuning was revised to give a short octave from C/E, since some points within the recorded repertoire are unplayable on a chromatic bass. Taking these factors into account, I wonder whether, although the pitch of the copy is a = 466, the instrument might date from as late as the early eighteenth century. In the Germanic countries, as the Museum of Musical Instruments of Leipzig university dramatically illustrates, this type of clavichord was very popular for at least a hundred years, disappearing only shortly before 1800.

Musically, the contrast between the two clavichords is dramatic. The clarity and variety of tone from the different areas of the compass and, as Charlston points out, the unusual dynamic flexibility, are undeniable. His own response was that the instrument cried out for the performance of Froberger. This is an instrument well worth hearing, and these qualities are all exploited by the player – at times almost to excess, if one has any pre-conceived ideas about how contrapuntal pieces should sound. But for those who enjoy the effect of contrapuntal lines overlapping and weaving a sonorous texture, the lack of sustain sound from this clavichord will be a problem.

Players can see (or imagine) the score, so that a note which has physically ‘died’ can still be heard in the head. For those who are simply listeners, the effect of hearing, for the most part, only the start of a note, can be frustrating. The treble of the instrument (as is normal) is particularly short-lived. In brief, this is an instrument which is difficult to play, and which requires effort too, on the part of the listener, except when the music is heard in small quantities which, with this restricted repertoire, is surely appropriate.

For anyone attracted to this CD, the towering figure of Jacob Froberger needs no introduction. Froberger designed his three books to contain balanced sets of every type of keyboard music popular in his day, and the booklet provides an informative introduction to his life and work. More useful to the student and even the seasoned professional is an essay on the music selected. This is deep and well-researched, concerned with sources, compositional techniques and styles; it includes a detailed commentary on each piece. Especially for those who play this music (and I can vouch for how enjoyable and satisfying this is), these scholarly insights can enhance understanding, and reveal not only the depth of scholarship possessed by Charlston himself, but what extra unnoticed pleasures this music has to offer.

Some of the Fantasias, which are played first, in order, display an entertaining feature shared with composers such as Orlando Gibbons, of beginning with grave, slow music which accelerates to an exciting conclusion through a reduction in note-values. The canzonas which follow are livelier pieces which incorporate toccata-like free material; they anticipate the praeludia of Buxtehude, and the early toccatas of J. S. Bach. In general, I found the canzonas more satisfying: they employ, on the whole, a livelier pace and shorter note values than the fantasias, and the decay of the instrument’s sound seemed to match more naturally the space which the brain was expecting each note to occupy.

Playing counterpoint on a clavichord is much more difficult than on a harpsichord. On a fretted instrument it is harder again, as only some suspensions are possible. This obliges players to avoid legato: any emphasis of a line or gesture that employs legato is impossible. A good player can, nevertheless, achieve a clean, disciplined presentation of contrapuntal textures. I vividly remember the late Christopher Kite performing Bach’s Well-tempered Clavier on a fretted clavichord. The technical achievement was remarkable but, inevitably, the effect was more academic than emotionally rewarding.

In this case, Charlston’s approach is seldom neutral. He is an expressive player, keen to communicate more than the intellectual satisfaction of neat counterpoint. He is therefore ready to exploit the dynamic capacity of this little instrument by, for example, diminuendos at cadences, subtle accents, and even an instinctive dynamic reinforcement of fugal entries, akin to that which today’s audience has come to expect from pianists playing Bach, but seldom from early keyboard specialists playing seventeenth-century counterpoint. It is, as Terence Charlston observes, possible with the clavichord, to hear this music in new and refreshing ways.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978