Fanfare

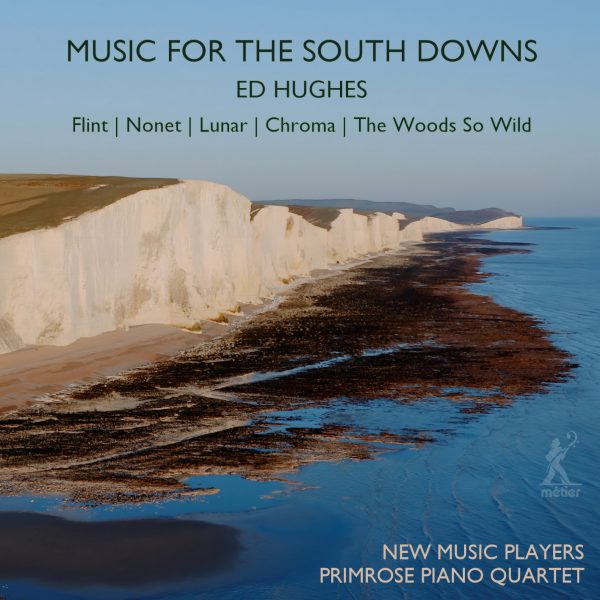

The music of Ed Hughes rarely fails to impress. A Métier disc of his music reviewed in 2020 (Fanfare 43:6) served to confirm impressions of a twofer reviewed in Fanfare 36:2. Here, Hughes uses his “lovingly patterned” music (Judith Weir, quoted at the outset of the booklet) to create an affectionate portrait in sound of the South Downs, a range of chalk hills extending to around 260 miles of south-east England. Hughes was commissioned by the South Downs National Park Authority to write a score to a film by Sam Moore, South Downs: A Celebration, marking the National Park’s 10th anniversary.

Beauty and affection are present in bucketloads here. Hughes’s musical vocabulary is wide, and while musical responses to countryside might conjure up images of the English Pastoralists, Hughes very much has his own voice, as the first piece, Flint, attests. Written in 2019 and scored for string orchestra, it is intended to evoke the chalk downs of the Sussex countryside with its sudden verticals and “cuts” (such as quarries, or where land meets sea). We hear the contrasts most obviously in the first movement, as well as elements of the idea of patterns undergoing process. The slow movement paraphrases an English folk tune collected by George Butterworth in 1912. Hints of Pastoralism are continually undercut and disturbed, adding a sense of disquiet before the finale brings it all together: a solo violin sings above a texture based on the song from the slow movement.

The Nonet dates from 2020 and was written for the present performers, the New Music Players. If one goes to Ed Hughes’s website, one can see the film. It’s highly recommended: the celebration of Nature and its changes is sensitively and beautifully done. Listening without images, though, puts the spotlight on Hughes’s processes. Edward Maxwell’s trumpet is notable for his accuracy over disjunct yet lyrical passages. Hughes speaks of the second movement as “like a walk in Winter sunlight,” referring to the more objective feel and the glistening textures; meditative, its influence is reflected in the finale, which in some ways hearkens back to the first movement but with a lighter textural and sonic feel, one that approaches joy.

Unsurprisingly the music turns inwards for the nocturnal world of Lunar, two studies for a quartet comprising flute, violin, cello, and piano. Inspired by an art exhibition at the Barbican Art Gallery in London by Isamu Noguchi that included wall-mounted sculptures entitled “Lunars,” Hughes’s piece takes the idea of objects that are simultaneously luminous and evocative of (strange) landscapes. The piece is actually a contrasting pair of movements, inner for the first then radiant for “Lunar 2.” The performance here is particularly noteworthy: The ensemble captures Hughes’s individual way with texture perfectly in the first movement before “Lunar 2” dances. There is a real sense of affection embedded in this performance, and the superb recording supports maximal detail.

Written somewhat earlier, in 1997, Chroma for 11 strings uses a layering technique applied to tempo, pulse, and rhythm that ensures a shifting surface, with a string quartet of solo players who act as a “center” with melodic elaborations all around. It is very much a shifting mass of sound; but the “mass” itself feels quite light.

Scored for piano quartet, The Woods So Wild (2020–21) was written for and dedicated to the present performers. Again, Hughes uses “found” material from England, this time the tune Will Yow Walke the Woods soe Wylde, possibly sung by King Henry VIII. It is interesting how Hughes dislocates the tune both metrically and harmonically, his own language contrasting with the song’s modal basis. The Primrose Piano Quartet players form a spectacular unit; their understanding of Hughes’s vocabulary is impeccable, as is their performance. A short second movement re-introduces the old tune before its end; the mood overall strikes me as crepuscular before the final movement grows towards an apotheosis. The composer himself points to his methodology here as using “cross-rhythms and weaving polyphony like the intertwining roots, branches, moss and leaves of a sunlit wood.” It works brilliantly.

More proof then, if proof were needed, of Hughes’s stature as a composer, all held in fine performances; this is a superb disc.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978