Plant Hugill

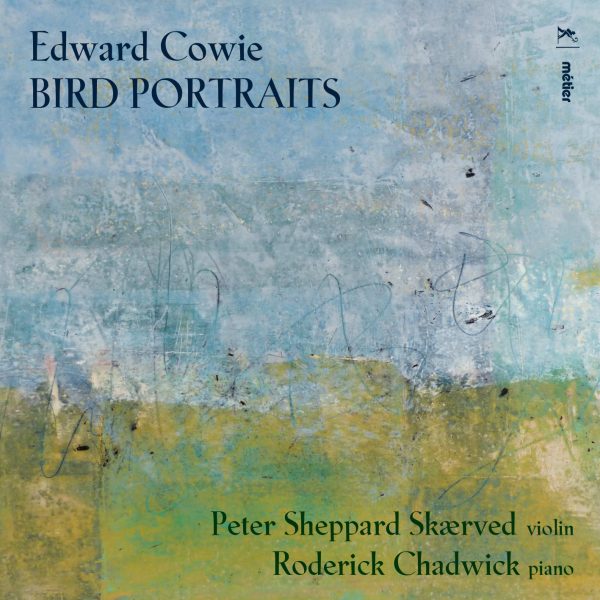

This new disc from violinist Peter Sheppard Skaerved and pianist Roderick Chadwick on Metier features composer Edward Cowie‘s new 24 movement work, Bird Portraits, a work which arose directly out of lockdown.

When we think of birds in music, then we immediately think of Olivier Messiaen but Cowie explains in his introductory article that his approach to combining music and birdsong is somewhat different. The music started from the notebooks that Cowie kept on his walks with his wife last year. They live in South Cumbria and one of the benefits of lockdown was the discovery of the large amount of bird life in and around their house. In his article, Cowie describes himself as a patterner, incessantly drawing patterns out of nature, both bird song and the natural background, the habitat.

Whereas, in Messiaen, the birdsong is the musical starting point for complex musical development, here Cowie is much more like Schumann in using the notated music as the core of a character piece. Each of the 24 movements is an independent piece, but they form a cycle and there are conscious and unconscious links between the movements and a sense of dramatic flow. The number 24 has significance for Cowie, he has written several other pieces of music in 24 movements, and birdsong too has occurred before; he reckons that around a quarter of his catalogue is birdsong based.

The birds are divided into four books of six, Water, Field, Wood/Garden, Sea birds, though you don’t have to know this and the results appeal simply as music. Similarly with the musical material, I have very little knowledge of birdsong and cannot comment on how close Cowie’s notated patterns come to the originals (bearing in mind that the songs of birds are both enormously complex and not intended as what we think of as music). But what counts is that the cycle creates a surprisingly satisfying musical whole.

The movements are quite short, and each is distinct and intense. The music can, at times, feel descriptive yet there is always a recognisable musical voice and whilst a lot of the material is spiky and tonally free, Cowie certainly does not shy away from tonality and lyricism. The piano does not strictly accompany, its role is to provide the background, the habitat which means that the piano takes on a distinct musical role in each piece, sometimes participating and sometimes providing a more slow-moving backdrop to the more mobile violin. The results can, at times, be remarkably visual and there are moments when the backdrop becomes more important than the foreground.

The performances from Peter Sheppard Skaerved and Roderick Chadwick are exemplary, sympathetic and committed, lyrical and virtuoso.

The CD booklet not only includes a long article by Cowie, but also shorter meditations by Sheppard Skaerved and Chadwick, written as thoughts about playing and recording the music. The result is a highly poetic contemplation of the creative process, and this is complemented by the disc’s cover image which is a painting by the composer’s artist wife, Heather Cowie.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

![🎧 Listen now to the @purcellsingers' first single from their upcoming album, #ASpotlessRose! ➡️ listn.fm/aspotlessrose [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/642752592_1424641949105789_8815810652567824072_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=106&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=iGIrDXgtiUoQ7kNvwHXsvX8&_nc_oc=Adn_HU665KIpQ8mH9kT5oGvpwQwSYeyaZdiK6y120drWTAvKs3DxjoTPt8xLgYgvPgo&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=ryySXiDHibQqRCyG8SHkvw&_nc_tpa=Q5bMBQFuR8cOk24lx2LL1CbHBWwdupHSbi-8eC9p6fjuge8fsUNDMx_C5gqu0rWNjAX70gl2SyJQDfZRpw&oh=00_AfxH00l3cUFj6FQpS_FI5eHZFFVVBk8Dp4hrltmvisSWuQ&oe=69B13F41)