Fanfare

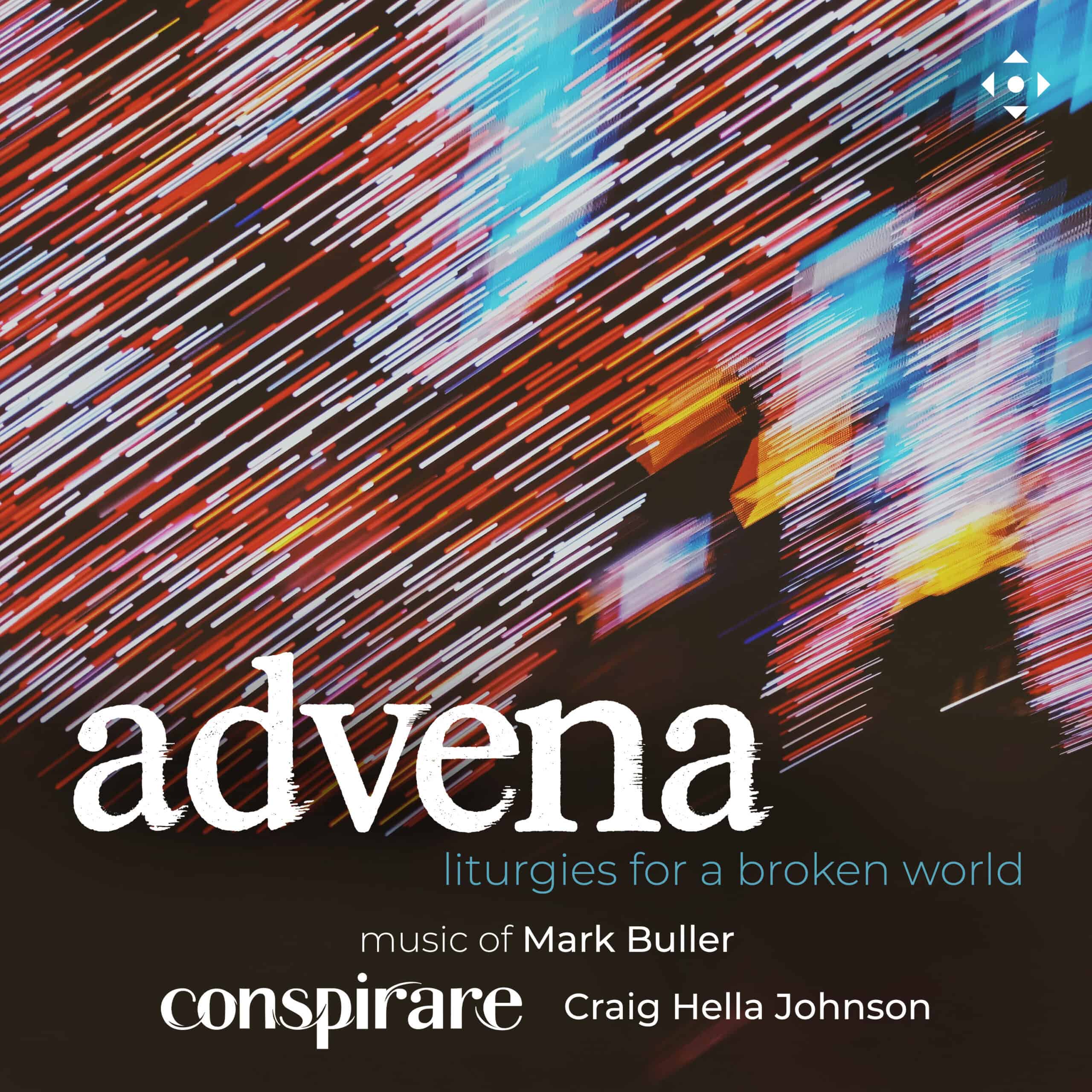

Although two librettists and four pieces of music by Mark Buller are involved here, they make a coherent whole. Introit: Fruit of Your Heart is to a libretto by Euan Tait; the larger Mass in Exile and Requiem in the Light have words by Leah Lax; and the final Communion: A Questioning brings us back to Tait.

The search for the light is a thread that winds through many religious systems. “Advena” is the Latin word for “stranger,” or “foreigner.” We are, posits Buller, living in a fractured world: distanced from ourselves and each other, and from the natural world. Introit is for choir and guitar; with the guitar performed here by Marc Garvin, who plays with a lovely sense of clarity. It is an “entering” into the two principal works and is clearly influenced by Plainchant (with guitar “commentary”). There is also a sense of questioning from the guitar, with the choir offering its response.

Mass in Exile came about as a response from the composer to the intermingling of religion and politics, and the amplification of that nexus. Mass in Exile again features a solo instrumentalist, this time violinist Patrice Calixte. The solo baritone represents the composer himself. It begins, though, with choral cries for “Mercy” against active, emotionally destabilized strings in the first movement, “For want of refuge (Miserere).” The text asks, “Where, is He, where is God?” Simon Broad is the fine singer here, burnished of voice; in contrast, “Credo in Exile” begins gently, on guitar. This is music of great beauty, exemplifying the dissonance of the invitation to pray and the world around us. Michael Hawes has a light edge to the upper part of his voice that works perfectly here, almost as if there is an edge of desperation. The choir acts as a massed invitation to the perceived solution (prayer). Buller has a very varied palette, and he uses it intelligently: from filmic to liturgical, the music’s trajectory is never in doubt. The choir, Conspirare, is simply superb (multiply reviewed in the pages of Fanfare, just never previously by myself).

The Gloria is entitled “Peaceable Kingdom” and opens with another gentle guitar solo. The text is a beautiful, erotic love song, Conspirare offing honeyed sound (appropriately, given the text). Buller achieves a sense of heart-centred music without tipping over into sentimentality. Calixte and percussion open “As water flows way (Prayer for the Government)” in highly contrastive fashion, with the percussive sounds indicative of prison bars; and then, at last, “Kyrie,” with its thought-provoking twist: “If I have no mercy, who am I? … if not now, then when?”

The “Earth Sanctus,” beginning with a closely-scored choral cry on the word “Kadosh” (holy), features bass Simon Barrad, offering a lovely, rounded voice. But it is Buller’s harmonies, so luminous, that are most impressive here: they glow with an inner reverence. The word “kadosh” also opens the Benedictus, “When all else falls away” (the text later quotes poet Yehuda Amichai). The Benedictus is clearly a place of peace, Hawes blanched at “When world and words fall away”; the music turns star-encrusted at the final entreaty for “peace without words.”

The Requiem in the Light pulls us absolutely into the present, but asks us to consider our past in “Lacrymosa for the Murdered.” The final words reference Jesus’s crucifixion, “perhaps the ultimate child murdered by the state,” as the booklet notes put it. There is an urgency here as the choir sings “Where did you go?” the pulsings possibly redolent of a fibrillating, anxious heartbeat. The “Confutatis: Morning Light” finds repeating string figures holding a kind of vibrancy against the long choral lines.

“Prayer to the Body: Domine Jesu” is a cry for freedom, and after that initial cri de coeur, the music cascades out until out of silence emerges a fine cello solo, lachrymose itself, by Doulas Harvey. All of the music so far has been expressive, and within a large envelope: but none has been expressive in the way of say, Verdi’s Requiem. So how will Buller set the “Dies irae”? Even Fauré’s Requiem has a measure of assertiveness here with those syncopated horn octaves. Buller’s response is the most (for this listener) touching moment of the entire disc. The text talks of our “shattered earth,” “receptacle of our poisons / and our rage.” The text clearly plays on an unyieldingness of spirit (“I will not yield”) and the giving up of the corporeal shell at death (“But when I yield” is the very next line, “Please / hold me. / Enfold me”). It is great writing, and Buller sets it beautifully, segueing into the final “Requiem (Agnus Dei)”: “This life / will be / a requiem / for an /unfinished song.” The setting of “song” is glorious, blazing with light.

And so to the epilogue to the disc; “Communion: Questioning,” and back to Tait’s text. A solo female voice opens. The words are beautiful, offering up the “risk of loving and being loved.” Interestingly, during the storm of life, love answers “softly / Not with rage or Dies irae”; which links rather interestingly to the previous piece.

A very moving album, well performed, recorded, and annotated. More, Buller’s music reaffirms music’s crucial role in reminding us who we are, and what is important. Recommended.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

We noticed you're visiting from United States (US). We've updated our prices to United States (US) dollar for your shopping convenience. Use Pound sterling instead. Dismiss

![🎧 Listen now to the @purcellsingers' first single from their upcoming album, #ASpotlessRose! ➡️ listn.fm/aspotlessrose [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/642752592_1424641949105789_8815810652567824072_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=106&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=iGIrDXgtiUoQ7kNvwG_aZR7&_nc_oc=AdlYFiaoBGValH-FIPy0pA8pHFJt8eQHmAUitzsVdQheo7aHgvc8LWz4CXKpwE8qKXc&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=fQYQ8Kv3XHjCQwbUcjTusw&_nc_tpa=Q5bMBQEYcdgv8S5MGYNmkdF6eOPouiE_dEJcd1gj1QNSkd7HlYuv-Gb62PNSeEhuHM1EV_pBNWBAnAAgwg&oh=00_Afw8_cyjhN5Cje_M6NoMA2wqA_njkJoF7HPcfr-2yiZVgg&oe=69B4FB81)