Fanfare

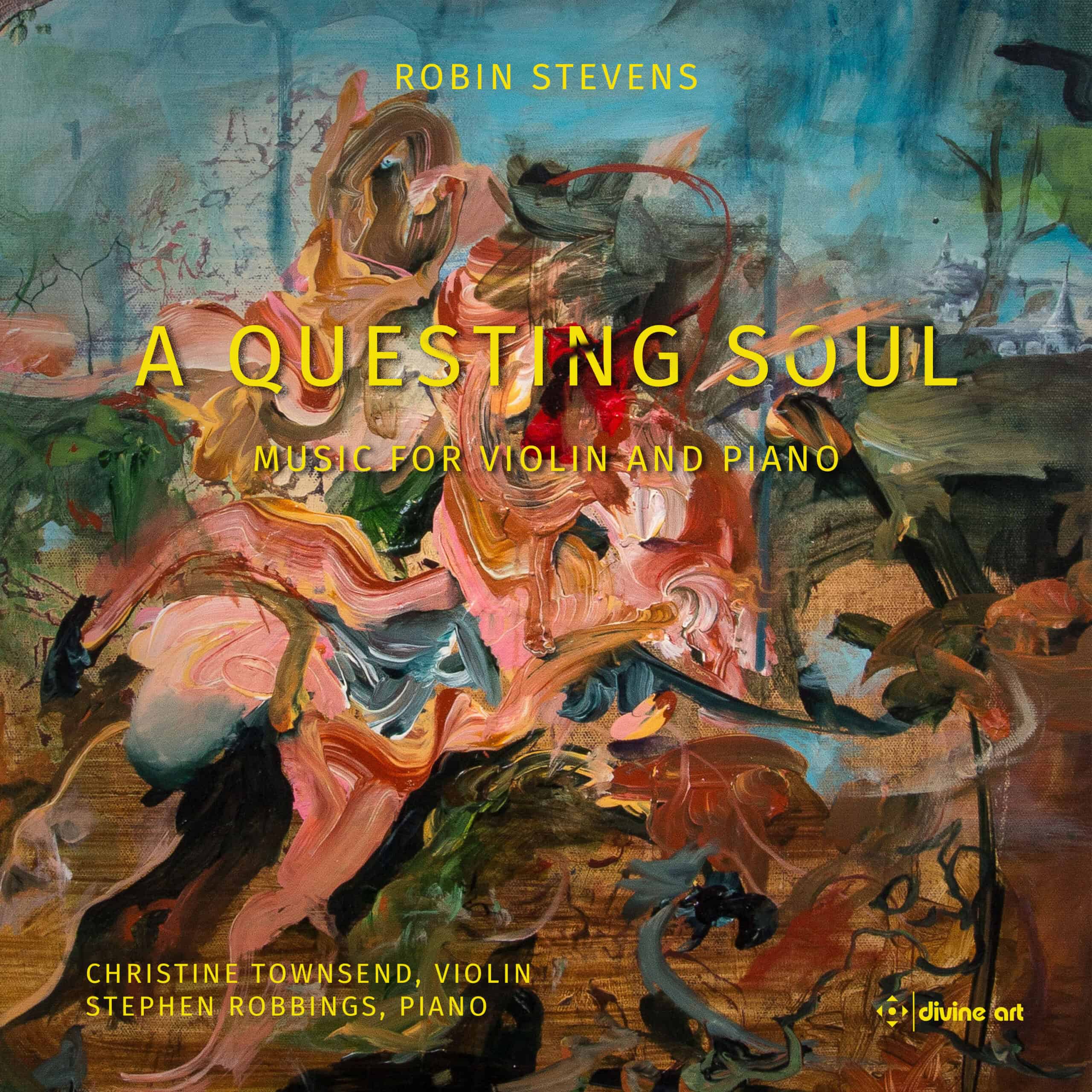

I took great pleasure from a disc of Robin Stevens’s chamber music in Fanfare 46:6. The present release (a twofer that extends just over a single disc’s playing time), entitled A Questing Soul, concentrates on Stevens’s music for violin and/or piano. The performers, Christine Townsend and Stephen Robbings, have been in a duo for decades, and it shows; this is a true chamber music partnership.

Something of a musical chameleon, Stevens’s music is richly expressive. It certainly is in the one-movement Fantasy-Sonata, along with the Sonata Tempesta both the longest and earliest music here. The Fantasy-Sonata is multicolored, often octatonically-based, and often beautiful. Christine Townsend plays beautifully, flexible when required and staunchly determined elsewhere; Stephen Robbings is the perfect partner, and both are caught in a fine recording.

The Toccata (for solo piano) is exactly that, a study in touch comprising a fast-moving line brilliantly, sparklingly delivered by Robbings. Stevens’s harmonic language is individual and clear; this would make a fantastic encore. The short Cri de coeur demands huge control from the violinist in the highest register, and Townsend is superb. The music floats, as if in suspended grief, with piano flurries indicating spikes of emotional pain; tonal, or quasi-tonal, passages seem to offer a potential way through. In this context, the solo violin scamperings of Stratospheric! seem to act as a prolongation to Cri de coeur, which includes another toccata, balancing the piano offering, that is flawlessly performed by Townsend.

Balancing all that angst is the rather more relaxed Scherzo in Blue for violin and piano, a blues progression meeting Stevens’s own mode of utterance, with passages of some dissonance vying with more consonant areas. The piano piece Reconciliation? that concludes the first disc is, as the booklet notes suggest, a mini-tone poem. Clusters (especially clusters that echo on) make a powerful effect, while Stevens plays with his various forms of material (lyric and consonant; angular and dissonant; a march) with some mastery. Robbings’ performance is clearly one of much preparation; it exudes understanding, so that consonant arrivals feel structurally right.

As was the case with the first disc, the second opens with an extended work: Sonata Tempesta. It does live up to its name, its stormy passages heard against moments of great lyricism; one particular melody for violin in the first movement is positively inspired. The feeble intensity of the Scherzo is perfectly captured here. This is a multi-hued scherzo, fiery and fleeing, its final enigma sustained in the lovely Andante tranquillo (ma non tanto). Here, harmonic consonance has a poignant part to play, so that this movement’s “cri de coeur” moment cuts deep. The finale is a nicely edgy rondo. It does require split-second responses between the players, and the razor-sharp playing here is very much integral to the performance’s success. Only a musical partnership of the caliber of Townsend and Robbings could negotiate the tricky metrical play of this movement with such aplomb and bring them to success. A fine performance of a work that buzzes with energy.

The solo piano piece from which the disc takes its name, A Questing Soul, is only about four minutes long. A sequence of abrupt juxtapositions, it makes maximal effect under Robbings’ fingers; spiky staccato chords perhaps indicate a sinister aspect. Balancing that solo piano piece is one for solo violin, Tom and Jerry. The piece is a tribute to Scott Bradley, the composer of music to the Hanna-Barbera cartoons, and a finely judged one at that.

It is a nice idea to present two sets of three pieces separated by a lovely piece called An Interrupted Waltz, especially as the central waltz changes scoring (from flanking solo piano to duo). There are other connections: “Beethoven through the Looking Glass” and “Master of the Rocking Horse,” the first and third of the Vignettes respectively, inhabit something of the same world as Tom and Jerry. The Bagatelles are earlier music, typical of the composer’s dissonant early pieces; Robbings finds the right sense of background dance to Tempo di Valse.

Written for a friend in the midst of a difficult pregnancy, Say Yes to Life combines play (and children’s phrases) with some real compositional grit. Finally, we have the solo-piano Soliloquy, which acts as a sort of partner piece to A Questing Soul.

Divine Art continues its valuable documentation of the music of Robin Stevens in style. Townsend and Robbings are a brilliant duo. Recommended.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

Search

Newsletter

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978