Fanfare

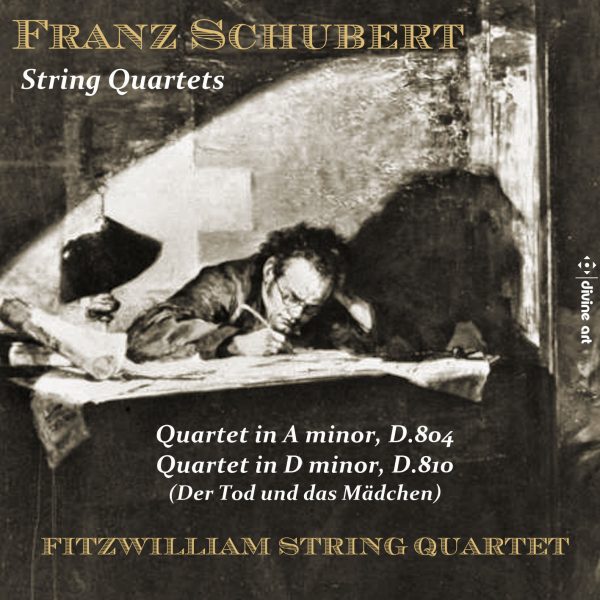

Despite the familiarity of Schubert’s “Rosamunde” and “Death and the Maiden” Quartets, there’s room for new discoveries, as abundantly proved by this thought-provoking release. The veteran Fitzwilliam Quartet had been out of sight and out of mind in my listening for a long time. Now they almost erupt into view, so striking and original is the music-making on this disc. Everything about the two scores has been rethought to the smallest detail, as described at length in the well-written, cogent program notes by violist Alan George. There’s too much to summarize here, but I can give the most salient points, which when taken en masse produce a very different sounding performance.

Heard in person the Fitzwilliams play with a big tone and a forceful presentation, phrasing broadly rather than in minute detail. That’s the baseline in these two Schubert quartets as well, but I was surprised by the unusual sonority being produced, until I read that the group was using gut strings. There is some degree of added mellowness to the overall sound, but what is perhaps more notable is that the violin’s E-string is softer, less prominent and bright, which affects the balance one is used to with a wire string.

If you prefer brilliance of sound to mellowness, it takes a little adaptation listening to the Fitzwilliam’s Schubert. Personally, I enjoyed the atypical sonority combined with interpretations that exude emotional warmth. Following historical precedent, vibrato has been excluded except for rare expressive effects. This adds to the pungency of the sound. Most HIP string quartets adopt a Baroque model for tempos and accents, but the Fitzwilliam pored over the best research into Schubert’s notation, which turned out to be more dramatic, contrasted, and sharply accented than modern practice, and certainly HIP routine, comprehended. The notes have a lot to say about accenting and dynamics in particular, pointing out that Schubert’s notation went to an extreme that was unprecedented except for Beethoven.

Many more points are covered, all of them intriguing and interesting, but the upshot is a forceful, highly expressive style, filled with variety and color, that also employs HIP understanding in the most precise sense, as applied to Schubert specifically. Not only are we faced with a surprising sound world, but the interpretations are so musical that I’d have to reach back to the Busch, Budapest, and Alban Berg Quartets for comparison.

It took over four decades, we are told, before the Fitzwilliam played these two staples of the quartet repertoire, their principal focus being on less familiar music. To provide a bit of background, the group was founded in 1968 by four undergraduates at Cambridge University (Fitzwilliam is the name of one of the University’s 31 colleges). More than 50 years later, one founding member remains, violist Alan George. First violin Lucy Russell is next senor, with 32 years in her position. After study at the Royal Academy of Music, the original group got their big break when Decca signed them to record a complete cycle of the Shostakovich quartets. On a visit to England Shostakovich had heard them play at York University, and he was impressed enough to entrust the Fitzwilliams with the Western premieres of his last three quartets. Almost serendipitously and existing in youthful obscurity, they became the first ensemble in the world to play and record all 15 Shostakovich quartets. (The complete cycle received the very first Gramophone Award for chamber music in 1977.)

Famous as they were for their dedication to Shostakovich—Quartet No. 8 was on the first public program they played outside Cambridge in 1969—it’s fair to say that on this side of the Atlantic the Fitzwilliam Quartet fell out of sight in other repertoire. But I like their Schubert far more than their Shostakovich, actually. Every movement has been rethought for tempo, phrasing, and sound. The quoted “Rosamunde” and “Death and the Maiden” themes in the Andantes are taken fairly quickly. Schubert didn’t take up using the metronome, but he happened to give a metronome marking for the song version of “Death and the Maiden,” which is adopted here. Particularly unusual is the folk-dance treatment of the finale of Quartet No. 13 and the accenting of the tarantella finale of No. 14. That’s not to minimize how mature and satisfying these performances are as a whole. However improbable it might seem when I compare them to the Busch and Budapest Quartets, online sampling will allow you to judge for yourself.

A final thought: In his program notes George brings up some intriguing autobiographical issues about Schubert. He makes the point that creative genius doesn’t depend on the life a composer happens to be living. Both of these quartet masterpieces were composed in February/March 1824. Schubert was 27 and had been diagnosed with syphilis two years before. In a letter to a close friend, Leopold Kupelwieser, dated March 15, 1824, he was in a gloomy mood, quoting a line of Goethe’s that appears in the Lied Gretchen am Spinnrade: “My peace is gone, my heart is heavy; never, never again will I find rest.”

If we commit the fallacy of mistaking the personality for the artist, the two string quartets from that same month should be equally gloomy affairs, which they certainly aren’t. Schubert would live with his dreadful diagnosis for another four and a half years. Much joyful music emerged during that period. The noted musicologist Jack Westrup commented that the first three movements of the “Rosamunde” Quartet are perhaps the most songful of any Schubert quartet. Speaking to the temptation to equate life with art, Alan George reminds us that “such speculations can be treacherous: remember that ‘Gretchen am Spinnrade’ was composed by a lad of seventeen, whereas the gloriously sunny B-flat trio appeared right after Winterreise itself, when [Schubert’s] demise was all too near at hand.”

We should celebrate the difference between the artist and his life, not scrape the bottom of the barrel looking for the roots of misery, discord, and disease. If disease and distress determined the output of a genius, literally every note of late Beethoven wouldn’t exist. His physical and mental travails were horrendous, and we know much more about them than we do about the relatively obscure Schubert. Many other examples could be put forward, which baffles those of us who are not geniuses. But the point is beyond dispute.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978