Fanfare

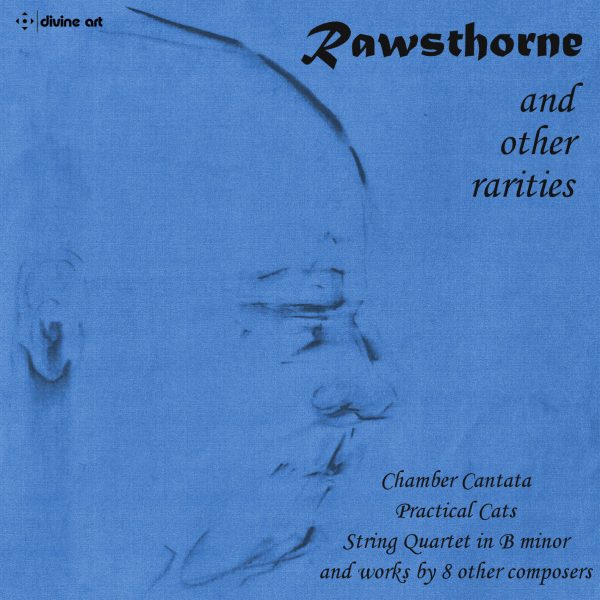

The rather odd title of this Divine Art collection—Rawsthorne and Other Rarities—is explained by the fact that in addition to three recording premieres of music by Alan Rawsthorne (1905-1971), there are also brief works by eight other composers with increasingly tenuous connections to him, by far the best being the five-and-a-half minute Sonata Piacevole by the American composer Halsey Stevens (1908-1989), charmingly performed by recorderist John Turner and harpsichordist Harvey Davies. (Turner was searching through the list of Stevens’s manuscripts at the Congress in the hope of finding other works written for his instrument when he stumbled on the manuscript of Rawsthorne’s Chamber Cantata, long thought to be lost.) The other works—tiny songs by Vaughan Williams, Arthur Bliss, and Basil Dean and recorder pieces by Karel Janovicky, Donald Waxman, Malcolm Lipkin, and David Ellis—are largely ephemera that add little to value of the album, which as it turns out is considerable.

The Chamber Cantata from 1939 is one of Rawsthorne’s minor masterpieces, a 12-minute setting of three anonymous Medieval poems (all in Middle English) and “The Night is near gone” by the Elizabethan Scottish poet Alexander Montgomerie (c. 1544-1610). The songs range from the austere and gravely beautiful (“Of a Rose is al myn song”) to the charming and whimsical (Montgomerie’s rollicking contribution), while “Winter Wakeneth al my Care” suggests a religious dimension rare in this composer’s output. The performance seems nearly ideal, with mezzo-soprano Clare Wilkinson negotiating the ancient texts as though they were her native language and harpsichordist Harvey Davies and the Solem String Quartet reveling in the work’s unique and appealing sound world. (As long as they were devoting nearly a half hour to non-Rawsthorne pieces, we could have used a much-needed new version of Lester Trimble’s Four Fragments from the Canterbury Tales, which is a close American cousin of the Chamber Cantata.)

Practical Cats is not, strictly speaking, a recording premiere, given that the orchestral version has been done several times, most notably in the performance featuring Simon Callow on Dutton (currently available as an iTunes download only). What is new is the piano arrangement by Peter Dickinson, which not only misses little of the original’s color but actually works even better as a kind of daffy Sprechstimme Lieder recital, not far removed from the Walton/Sitwell Façade. If not quite as masterfully ham-on-rye as Callow, then Mark Rowlinson delivers T. S. Eliot’s celebrated verses with a droll, stiff-upper-lip seriousness, with pianist Peter Lawson laying down the perfect musical bed. Even confirmed dog-lovers will find it difficult not to respond.

The major discovery here is the early String Quartet in B Minor, written in 1932 or 1933 when the composer was still in his mid-20s. Well received at its London premiere but eventually withdrawn because the composer came to feel that the lovely second movement didn’t quite jell with the darkly menacing opening fugue and the hell-bent-for-leather finale, it’s a hugely accomplished work for such a late-blooming composer and is full of hints of things to come, not the least of which is Rawsthorne’s chronic aversion to wasting a second of the listener’s time. It’s a work crowded with incident, intelligence, and personality, and the Solem String Quartet obviously relishes each of its scant fifteen minutes. For anyone interested in 20th century British music this is an extremely desirable introduction to one of its still-neglected masters; for Rawsthorne fans, it’s an absolute must.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978