Fanfare

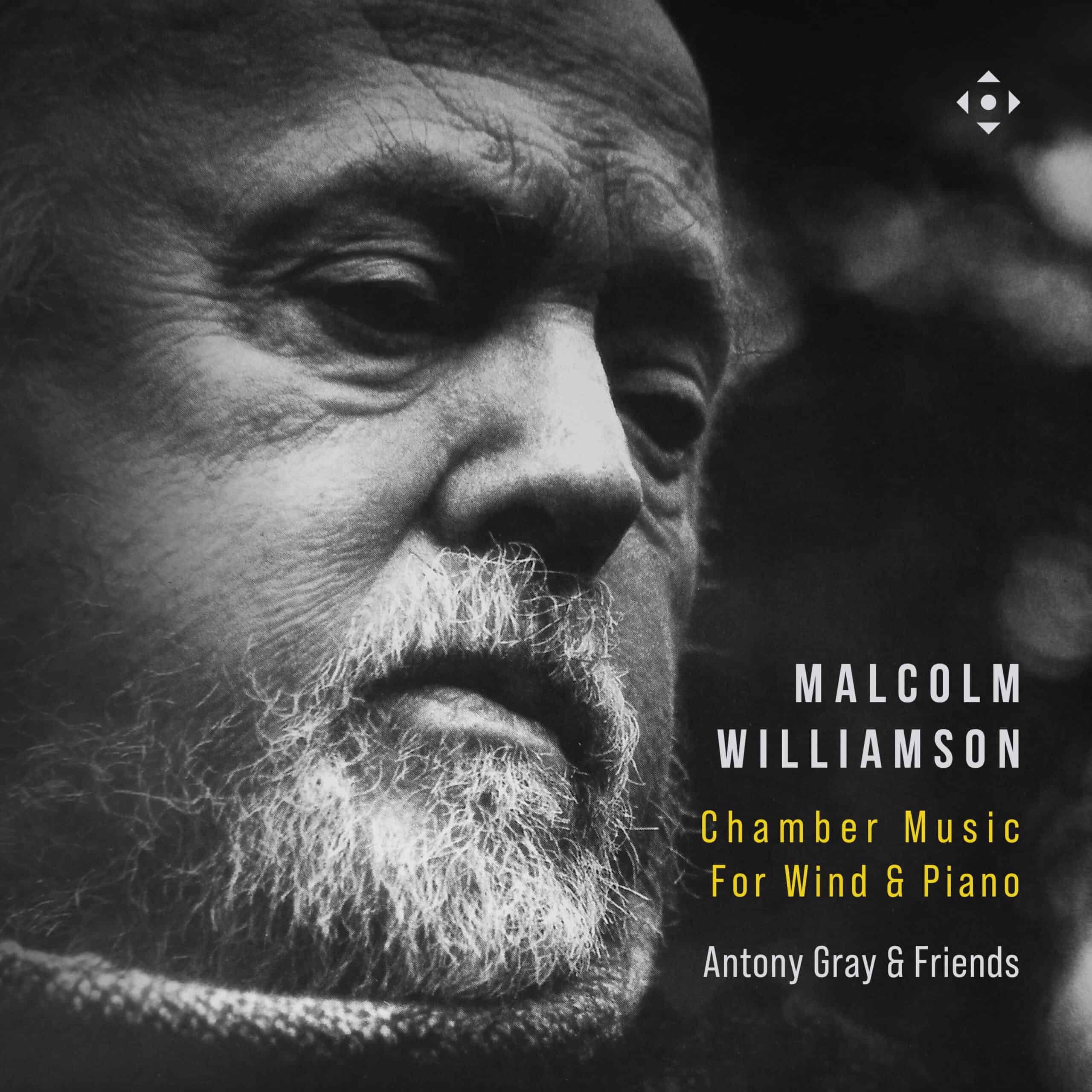

Since I am known—if I am known at all in reviewing circles—as one who sticks to Mussorgsky’s Pictures and first recordings of contemporary music, it may surprise the reader to see my name appended to the end of a review of the music of one of the best-known British (well, Australian, to be picky) composers of the century just past. The answer to this enigma is the fact that most of the works on this well-filled disc of this former Master of the Queen’s Music are first recordings, despite the dozens if not hundreds of LPs and CDs that contain other works by him. Being a decades-long fan of his music, the receipt of the disc from Fanfare Central was most welcome. These “unknown” works by the master span the gamut of his compositional style and career.

I shall consider together one group of works, the eight Gallery works which are scattered about in this recital, and for a good reason: they are all very brief (all under 50 seconds, and most less than half that length) and bear significant resemblance to each other. These are products from 1966 and constitute music that Williamson wrote for an eponymous British television show. Thus, these vignettes were for opening or closing music or transitions between scenes. The majority of them provide the last word in “mechanical music” and are highly rhythmic and propulsive, the type of music that would have worked perfectly as underscoring for the machinery in Chaplin’s iconic film Modern Times. Each is scored for the unusual combination of six trumpets, two pianos, and percussion.

The remaining longer works I’ll address more or less in program order. The first of these is Pas de quatre, written the following year after the Gallery pieces, for wind quartet and piano. The suite is cast in six contrasting movements, a very busy and exuberant Allegro vivace that is followed by two variations, a pas de trois, a pas de deux, and a coda. And, yes, this is music that could be danced to with considerable success, despite some occasional irregular meters. Some of the movements (such as Variation B, restricted to two woodwinds and seemingly the composer’s take on Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks) confine themselves to subsets of the entire ensemble with considerable success. Despite the composer’s sometimes prickly and curmudgeonly personality, this is music that is nothing short of delightful.

The two Vocalises, both for clarinet and piano, are created with lovely lines in the solo instrument decorated with gentle figuration in the piano. Sandwiched in between these is another work for the same forces, the “December” movement from the composer’s cycle Year of Birds, thought by scholars to have been intended by him as a stand-alone piece. It indeed nestles comfortably between its two bookends and impresses the listener as essentially a third Vocalise. Willamson’s brief two-movement Trio adds a cello to the instrumentation of the preceding three works. The opening Poco Lento is a quiet movement in which the cello carries most of the tunes with the clarinet and piano often providing birdlike figuration as commentary. The second section speeds up the proceedings by several degrees, but continues the employment of long lines—again often in the cello—complemented by the other two instruments. It’s a most effective and ingratiating work that I wish had gone on a good bit longer, given my captivation by it.

Williamson had a special affection for Scandinavia and even knew Swedish well enough to translate some texts in that language into English in order to set them to music. In Pietà, however, he foregoes the translation and sets Pär Lagerkvist’s text in its original Swedish. The 1973 song cycle was commissioned by the Athenaeum Ensemble and is a good bit more austere than most of the works gathered together on the present CD. The cycle, a meditation on the Virgin Mary, reflects its composer’s conversion to Catholicism some years prior. Its somber nature as she reflects upon her crucified Son may have been consciously applied by Williams to his musical setting here. The addition of oboe and bassoon to the usual piano accompaniment of song cycles lends a certain piquancy to the sound.

Music for Solo Horn receives no discussion in the booklet, but may have been one of the numerous works the composer wrote for various musician friends. The work is quite lively as horn works go, and includes a fair number of quickly repeated notes. An interior panel slows down the pace, although I doubt it gives the soloist much time to catch his breath before the lively activity resumes. The following Concerto Fragment reverts to (and even exceeds) the austere sonorities of Pietà. Again there is no information given about this minute-and-a-half snippet of an unfinished work for three pianos.

The program concludes with its longest work, the 24-minute Concerto for Wind Quintet and Two Pianos (Eight Hands), a combination possibly unique in the history of music despite its being confined to conventional instruments. After a slow wind intro, the eight hands on the two pianos burst into the heretofore serene lines with a fusillade of fortissimo tremolos guaranteed to instantly rouse any listener whose eyelids may have become heavy. The near-equal disposition of parts between wind players and pianists’ hands produces a sound unlike that of any other work I’ve ever encountered, and I suspect that few of Williamson’s many fans would recognize this work as his if they did not already know it. The Concerto was one of numerous commissions the composer received upon the successful premiere of his opera Our Man in Havana, and was intended to honor British composer Alan Rawsthorne on the occasion of his 60th birthday.

The first three movements are more or less quite laid-back, with some long passages in which the piano ensemble is silent, but the final one, containing far more notes than those preceding it combined, is busy, dynamic, and loud throughout, making a stunning closer for the recital.

Performances of this outstanding composer’s “chips from the workbench” are uniformly fine, and this unknown music should take its place proudly alongside the many masterpieces produced by Malcom Williamson. My usual high recommendation, as befits any composer whose music I admire.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978