The Art Music Lounge

Edward Cowie is one of the most instinctively and naturally talented people I know of. We now have a pleasant interaction occasionally on Facebook, but only because I started from a position of being in awe of his music in earlier reviews and he has responded to those kindly and modestly. In addition to being, as he is known in his native England, the finest living composer who bases his music on the sounds of nature, he is also an extraordinarily gifted and natural visual artist who has graced the otherwise vapid content of that social media site.

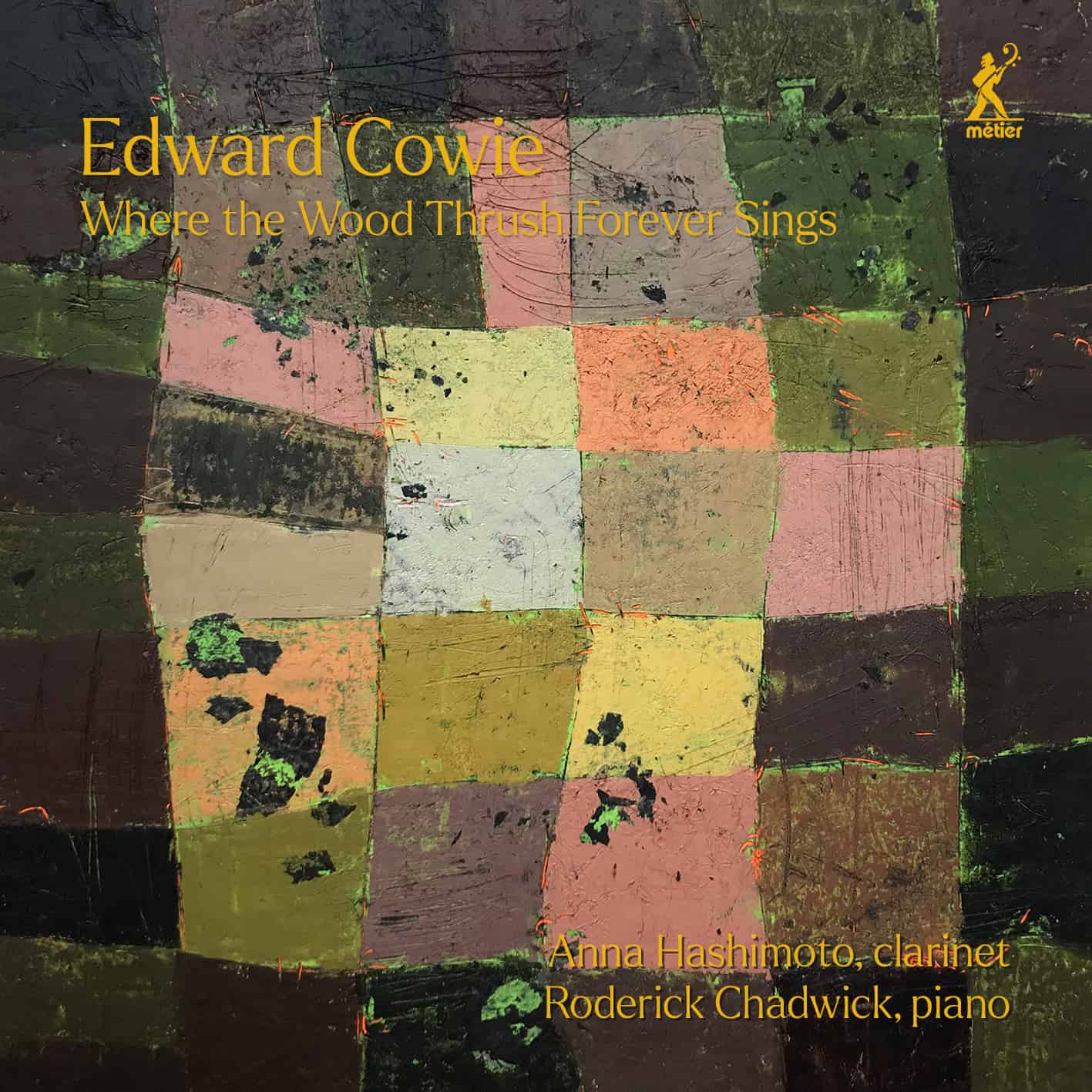

Incidentally, the artwork on the cover of this album was made by his wife, who is also a talented artist. In this new collection, his musical sketches concentrate on aural impressions of American birds, which for me, at least, is good because I’ve seen many of them in real life. (And believe me, sometimes I wish we could get rid of the blue jays in my neighborhood because they are the NOISIEST damn birds in the world!)

Delicately scored for just two instruments, this music typifies Cowie’s approach. His music is tonal and consonant when the bird calls he is emulating are so, but as we all know, birds do not follow the well-tempered tonal system so they are often quite outré harmonically. His portrait of the American Fish Crow which opens this album is a typical mixture of tonal and atonal, simply by following the utterances of this bird. It is to her credit that clarinetist Anna Hashimoto really gets into the spirit of the music, doing her best to make her instrument “speak” like a bird, which is amazing when you realize that she is an urban woman who has lived her entire life in London. Pianist Roderick Chadwick also does his best to get into the spirit of this music. As he put it in the liner notes:

being good at musical detail and the big picture) included performing three musical lines at once – a melody and two rhythms – and Anna was renowned for her ability to do these often without fault. This, allied with her questing mind when it came to exploring new repertoire and new sounds, and her generosity, focus and calm in the recording studio, made her an ideal partner for setting down this latest 24…

It was no surprise that, at the first rehearsal, our ‘inner metronomes’ were well in sync. If anything it became a matter of loosening the laces of the ensemble because, as Ted Hughes put it in ‘Pibroch’: This is neither a bad variant nor a tryout. Nature doesn’t rehearse.

Trying to describe this music in words produces, for me at least, a paralyzing effect. The closest I can come is to urge the reader to listen to some of Olivier Messiaen’s bird music, and he wrote a great deal of it because he considered birds to be almost mystical creatures, closer to the God of creation than humans. I don’t know if Edward feels the same way, but his ear is as keen as his skill in painting with watercolors (I speak from personal experience, one of the most difficult mediums to work in), and the end result is simply mesmerizing.

Another thing that struck me is that, if you simply put the recording on, sit back and take it all in without checking things, these various bird call imitations blend into one another. Of course this wouldn’t be possible if one were listening to tapes of the actual birds, since each one makes its own distinctive sound, but as transferred to the clarinet (Anna mostly plays the Eb instrument because she feels it has the greatest range of expression) the only clue one has of a “change of bird” are the luftpausen between tracks. Although this is a 2-CD set, the playing time is just seven minute too long to fit onto one CD, running a shade over 89 minutes, so it’s not a terribly long journey through the panorama of American birds.

Chadwick, as I say, also does his best, but since bird calls are a vocal sound and the piano is not an instrument that can simulate vocal sounds of any kind, he has a natural barrier between him and his intent. (The same thing is true in Messiaen’s piano music; being a percussion instrument, the piano can only do so much, although a few isolated geniuses like Paderewski, Cortot and George Shearing could get more out of a piano’s sound than anyone else.)

I was a bit surprised when Hashimoto simply blew air through her instrument in various places during her performance of “Broad tailed and Blue throated humming birds,” but to be honest, hummingbirds are rather rare in my neighborhood and so I very rarely see them—and almost never hear them, so I’ll take Cowie’s word for it. Then, during the course of “White Winged Dove,” Chadwick knocks around the inside of the piano frame. It’s all quite mesmerizing in its own low-key way. And I can assure you that Cowie captured the sounds of the Blue Jay. Mockingbird and Northern Cardinal exactly right. I’ve never seen or heard a Northern Goshawk, but this bird apparently has a very atonal and syncopated call to judge by the music, particularly the piano part which is the most rhythmically active in the set.

In a way, however—and this is hard to put into words—this is music that I liked hearing once, in the moment, as if I were attending it in a concert hall, the same way I would enjoy hearing the actual birds themselves, but not the kind of music I would listen to again for a year or two. Perhaps Cowie did his job too well, reproducing the sounds of these birds so well that they will surely appeal to those who do not hear most of them on a daily basis but not to those who do. As a tour-de-force for the musicians involved, however, I highly recommend it. I don’t think it is possible to sound as much like birds captured in the sheet music any better that Hashimoto has done.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978