Fanfare

The development of Spectral music arose in France in the early 1970s through works by such composers as Gérard Grisey and Tristan Murail. In this music, timbre is brought to the forefront, such that sound itself is in a sense “composed.” To effect this, composers using this system have employed computers to analyze sound patterns, and have also engaged in the study of human perception of sound. These composers have sought to motivate the listener to engage in what has been called “the eroticism of hearing” to induce pleasure through what Grisey has seen as “the result of a perfectly parallel relation between the perceiving body and the conceiving spirit.” I heard him give a lecture on the subject, in fact, about 20 years ago at a pre-concert lecture for a work of his that was being performed by the Los Angeles Philharmonic. The main thing I remember about the piece itself is that he completely reshuffled the seating of the orchestra—if I recall correctly, one of the bassoons was sitting where the concertmaster normally sits, for instance. All of this was done, presumably, to enhance or modify the sonorous constructs in his piece (which I did enjoy, incidentally).

This might all sound arcane to some readers, and I suppose if I were omniscient I would be able to hear some of you thinking, “Well, that’s all well and good, but how can an essentially monochromatic piano play a piece devoted to timbre?” That’s a good question, and I think the answer could be better heard than explained, so if you want to really understand what Spectral piano music is, a few minutes of listening will be far more valuable than my attempted explanation in this review. If one picture is worth a thousand words, sometimes a few phrases of music can also easily be worth that many.

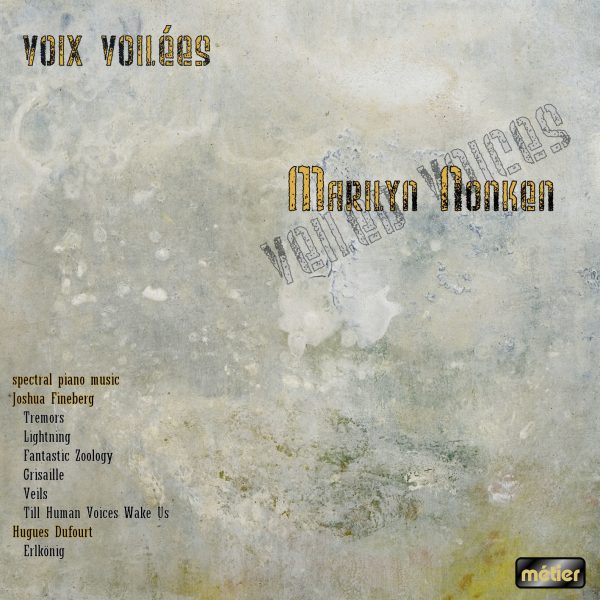

Nevertheless, realizing that few readers will want to purchase a CD just to find out what a reviewer is talking about on some technical matter, I’ll plow forward. Most of the works on this CD have been composed by Joshua Fineberg (b. 1969), an American composer who studied with Murail in France and Moshe Cotel in the U.S. His first work, Tremors, explores sound through punctuated rather dissonant chords and the natural acoustic decay that results when the sustaining pedal is kept down. Lightning, on the other hand, is a 10-minute work that builds up to its climax much in the way a thunderstorm builds up. In this case, there are 14 musical phrases through which the building up is accomplished. Some fancy footwork on the part of the pianist is required in this work to raise and lower the dampers at just the right time to create the effect the composer is seeking here, and I also note that a pedal point, centered on an upper G and its semitone neighbors, permeates the piece.

Fantastic Zoology draws its inspiration from three movements (“Papillons,” “Coquette,” and “Réplique”) from Schumann’s Carnaval. Fineberg’s treatment of this material is described in the booklet as “whimsical and macabre.” Maybe, but whatever it is, I doubt you’ll recognize the original works in this any more than I did. There are lots of tone clusters in the upper register of the piano in the first movement, while the second covers a good bit of the keyboard in a fashion seemingly designed to obfuscate any formal structure, and the piece closes with a brief movement that incorporates seemingly random gestures into dense textures. In Grisaille, one encounters Fineberg at his most virtuosic. The title comes from the monochromatic painting style of certain Renaissance painters (although Picasso also utilized it in his Guernica). Fineberg actually draws upon about as many colors as the piano is capable of in this work, intending to represent the melding and transforming colors on a painting’s surface over its monochromatic underpainting. I found this work to be among the most interesting and engaging in the recital, given its coloristic effects and overt virtuosity. The latter seems to be used structurally in the piece, and is not included just for its own sake.

In Veils, Fineberg is seeking to represent the veils that according to Tibetan Buddhist belief obscure reality from the unenlightened. (I was unaware of this concept in Buddhism, which has a similar one in Christianity, spoken of in the fourth chapter of II Corinthians). In his exploration of this metaphor from perspectives of philosophy and form, Fineberg has drawn upon the proportions and pacing of recordings from Tibetan rituals. The effect is quite evocative of a world far removed from our own fast-paced American society. The final work herein by Fineberg is Till Human Voices Wake Us, which was written in memory of French composer Dominique Troncin, himself also a pupil of Murail. His life and death are suggested by the life and death of the sounds of the piano, where a long decrescendo is punctuated by two-note intervals.

The CD concludes with the half-hour-long Erlkönig of Hugues Dufourt, also well known in French avant-garde circles. Death also plays a significant role in this work, just as it does in the Schubert Lied that serves as its inspiration. Here the writing is often far more aggressive than even the relentless driving rhythms found in Schubert’s masterpiece, such that the pianist is confronted with seemingly endless pages of black notes and virtuosity. The notes refer to the listener’s perception of strain and exhaustion on the part of the performer. True enough, but I feel exhausted just listening to Nonken play all those notes! It’s a good exhaustion, however, similar to that of the runner who has just won the Boston Marathon.

Marilyn Nonken negotiates the immense technical and musical challenges of these works in remarkable fashion. Her ability to get inside these demanding works has undoubtedly been developed through her study with David Burge, himself a pianist specializing in new music. This well recorded disc is self-recommending to readers who will know from this review whether they will be receptive to music of this sort. However self-recommending it may be, though, I recommend it too.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978