Fanfare

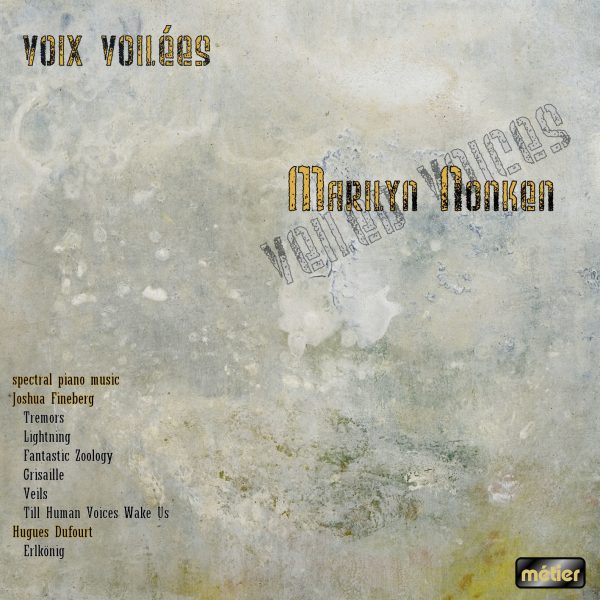

Marilyn Nonken has previously released the complete piano works of Tristan Murail for Métier (as well as recording for other labels: a CRI disc of music by Finnissy, Babbitt, and others looks fascinating, CD877). Murail’s use of spectral procedures is, along with that of Gérard Grisey, “first generation.” Joshua Fineberg (born 1969) wrote Tremors in 1997. Music of extreme contrasts, the super-quiet vies with violent, craggy chordal shocks. Written six years earlier, Lightning is cast in 14 “phrases” that interact with each other, gathering thickness of texture and velocity. The composer attempts to capture “after-images” of the violence via having the pianist raise and lower the dampers as soon as possible after each phrase’s final attack. The effect can be heard clearly on this recording.

It was the Schumann of Carnaval that inspired the set of pieces Fantastic Zoology (2009): “Papillons,” “Coquette,” and “Réplique,” while the title refers to Luis Borges’ Anthology of Fantastic Zoology. The opening is like Schumann behind a veil, perhaps, although soon the chosen gesture takes on a new, almost electric, life of its own. These three pieces are of Webernian brevity (the longest is 1:37). “Coquette” is remarkably dark, the lines slithering in a shadowy space; “Réplique” similarly morphs the original into a nightmarish area. Nonken’s performance is remarkable in that she seems so intimately attuned to Fineberg’s mode of discourse.

The work Grisaille (2011) takes as its starting point a type of monochrome painting that could serve also as an underpainting. In that sense, there is an underlying idea here that plays with what we hear at the surface level of hearing. This is a fascinating piece, its repetitions far from these of Minimalism; instead, it is as if the composer is turning the notes in his hands, trying to look at the same object from different angles. There is more taking a basic underlying idea that is obscured in Veils of 2001, this time the Tibetan Buddhist idea of reality being concealed by a set of veils. Recordings of Tibetan ritual have shaped this work’s sense of proportion, while Fineberg invokes Tibetan gongs and other percussion instruments during the course of the work. This is a stunning piece, in fact, beautiful and transcendent. Nonken has, touchingly, dedicated this recording to the much-missed composer Jonathan Harvey, a composer whose resonance with Buddhist ideas and practice is well documented. The trills of the central section have a vibrancy all of their own.

Another departed composer inspired Till Human Voices Wake Us of 1995, this time Dominique Troncin. The title comes from T. S. Eliot (“The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”; the line actually is completed by “… and we drown”). The piece is brief (just over two minutes) and comprises a diminuendo, interrupted regularly by dyads. Nonken says it better than I could: “It is a single breath, in the course of which we become attuned to the life and death of the sound.”

Half the disc’s playing time is taken up by Hughes Dufourt’s 2006 Erlkönig, one of four “meditations” on Schubert by that composer. While Schubert sought to imply the terror (and horror) of Goethe’s poem via repeated triplets on the piano and ever-rising cries from the child, Dufourt’s expansion takes everything to extremes. This includes technically, for the demands are huge. But there is tenderness aplenty here, too, an emphasis on the starry beauty of the quietly disjunct. The pianism here is terrific: Nonken’s finger strength in the loud passages in particular is massively impressive. That said, she treats many of the quieter passages with an attention to texture and touch that one might more readily associate with a sensitive interpreter of the French Impressionists.

Nonken, in her perceptive booklet notes, refers to the distinguishing factor of these composers (and of Spectral music as a whole) as “the embrace of the liminal space, that of openness, ambiguity, and becoming.” Perhaps for all the complexities of understanding spectral music and its techniques, one should hold this statement in mind above all.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

We noticed you're visiting from Latvia. We've updated our prices to Euro for your shopping convenience. Use Pound sterling instead. Dismiss