Fanfare

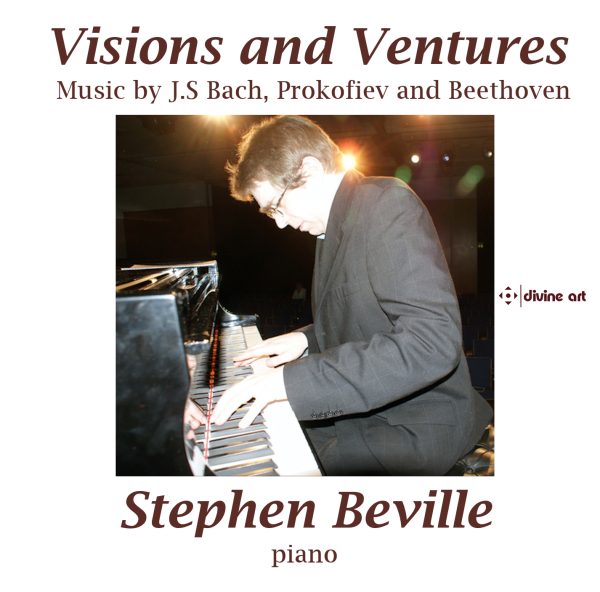

In his liner notes to this collection, Visions and Ventures, British pianist Stephen Beville claims he seeks “Visions both utopian and evasive … ventures towards and away from … forays and escapades [that] broadly characterize the keyboard music featured on this recording.” Beville opens with the Prelude and Fugue in E Major from WTC II, a work that integrates a sense of piety into a strong, improvisatory prelude in binary form, whose polyphonic texture gravitates to the dominant, in seamless motion in four parts. Under Beville’s hands, the stately fugue assumes a poised nobility of line, again conveying a poignant, reverential affect akin to the spirit of the B-Minor Mass.

Beville proceeds to the 20 pieces of Sergei Prokofiev composed c. 1914–16 under the title of Visions Fugitives, after the lines from the poet Konstantin Balmont: “In every fleeting vision I see worlds / Filled with the fickle play of rainbows.” Composition instructor Anatoly Liadov felt that the young Prokofiev had become “tainted by Modernism” in this work, written in a laconic, often witty or sarcastic mood as miniatures or character-pieces. The assemblage, not often played as a unit, reveal some common characteristics within their essential, ternary structure: disjunctive melodies that do not necessarily end emphatically; thirds and seventh chords that destabilize the harmony; chromatic melodies that abruptly shift to distant tonalities; dramatic dynamic contrasts; the use of the tritone; homophony in the bass reminiscent of a lyrical nocturne; free counterpoint. Beville identifies four as “quintessentially Prokofievian”: No. 1 (Lentemente), No. 8 (Commodo), No. 11 (Con vivacità), and No. 16 (Feroce). I would add No. 10 (Ridicolosamente) for its kinship to the op. 17 Sarcasms. Those experimental and rife with harmonic dissonances, as well as rhythmically percussive, are No. 14 (Assai moderato), No. 15 (Allegretto), No. 17 (Inquieto), No. 19 (Poetico), and No. 20 (Lento irrealmente). The tenor of the works seems coldly clinical, as in No. 2 (Andante), with its tolling figure. The pieces emerge as acutely acerbic studies in touch, compressed toccatas whose character might possess allure or uneasy intrigue, as required. A brief piece like No. 5 (Molto giocoso), lasting a mere 23 seconds, makes potent demands on Beville’s wrist articulation. The glistening sonority of No. 7 (Pittoresco “Arpa”) compels Beville to accord it special attention in his notes. Simultaneously enchanting and unnerving, these pieces reveal the mental and musical vigor of their creator.

Beville sees what he terms “revolutionary optimism” in the 1796 “Grand Sonata” of Beethoven, a work which received a 1972 recording of extraordinary breadth from Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli (DG 2530197). This Sonata No. 4 in E flat Major already projects the “heroic” impulse we find in later works, especially in the “Eroica” Variations and “Eroica” Symphony. Always seeking to resolve a dramatic conflict, Beethoven in his first movement Allegro molto e con brio, pits the tonic against the dominant B flat Major. Beville makes splendid, often jabbing, colors in his realization, imposing a strong sense of formal outline for the sonata form. The swirl of eighth notes makes its own impression as to Beethoven’s capacity for virtuoso technique. No less apparent are the bold procedures, such as harmonic wanderings or what commentators term “circuitous routes” in the passing harmonies in Beethoven’s development section. The playing of the coda projects a robust vitality.

The emotional heart of the work lies in its broadly expansive Largo, con gran espressione in C, as close to an operatic scene as Beethoven might compose later for Fidelio. Dramatic pathos collides with pregnant silences, only to emerge with fragments and compressed gestures in sometimes explosive dynamics, typical of Sturm und Drang sensibility. One might imagine the music to juxtapose moments of defiance against moments of religious or pious contemplation, anticipating the tension in his op. 13 “Pathétique” Sonata, where the chromaticism of Beethoven’s pain confronts the diatonicism of his will. Good spirits return with impelling force in the ensuing Allegro third movement, a humorous minuet and Trio whose discourse becomes increasingly animated, interrupted only briefly by the Minore Trio section that, again, bristles with a sense of impassioned revolt. For his last movement, Rondo: Poco allegretto e grazioso, Beethoven returns to the dynamic tension between E flat Major and B flat Major. But a potent, third motif in C Minor adds once more a sense of Beethoven’s future explorations in both sonata and symphonic expression. The last surprise lies in an excursion into E Major that eventually makes its way to the security of the tonic key. This is a stylish, adventurous recital, well balanced and technically impressive.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

We noticed you're visiting from Latvia. We've updated our prices to Euro for your shopping convenience. Use Pound sterling instead. Dismiss

![🎧 Listen now to the @purcellsingers' first single from their upcoming album, #ASpotlessRose! ➡️ listn.fm/aspotlessrose [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/642752592_1424641949105789_8815810652567824072_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=106&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=1oI-Pe3rGJ4Q7kNvwGTCquZ&_nc_oc=Adnyk0Vd3LjOuhKABRozm7KzfFOFBMD2rkRtxI9QokJxZryQOnhe2pO-WJNFFPudfGR9xVXpYMO5F8ODTa03k2rF&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=a3ey-IZ3dysqq1fkm-ge2g&_nc_tpa=Q5bMBQFBF_WeaipwLi-ek54xChrsl2n-TmLOasm25h-7CsYkaAA4fzNRFj7IsHafg1_AZ7hmITILCVCw7A&oh=00_AfttwPpwe29Bg7Z5SolU5hdODVYPSMugP8AWyxTYKAtNng&oe=69A95641)