Fanfare

One of the more interesting features of the New Virtuosity movement is that instruments long out of fashion or relegated to history were revived, with new music being written for the soundscape that these provide. One of the earliest of these was the harpsichord, which found new expression in the music of, for example, György Ligeti. But everything from this keyboard to Renaissance consorts were reinvented to contribute their unique sounds to contemporary music. Of course, this was not entirely new; one only needs to be reminded of Paul Hindemith composing for the viola d’amore in 1922, but this was an anomaly until relatively recently. Fusionist composers today feel free to use whatever instruments are available, old or new, borrowed or blue, acoustic or electric, to expand their own sound worlds.

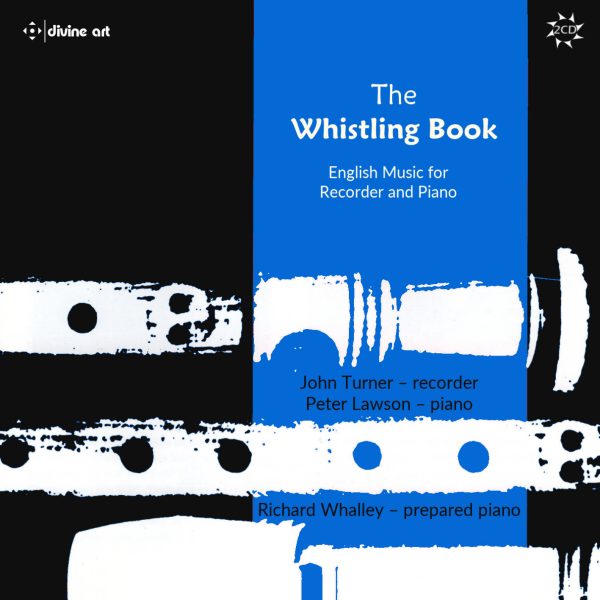

The Whistling Book focuses on just one of these revived early instruments, the recorder (orrather recorder family), taken from a series of pieces by Geoffrey Poole written to “amuse the composer’s young son,” as the booklet notes state. This apparently inspired a number of English composers to reconsider the facility of this early instrument, writing new music to accommodate its unique sound qualities. In 1988, the first version of this disc was recorded by John Turner and Peter Lawson. Its revival in 2022 by Divine Art needed some extra pieces to fill out the set, and so they added Richard Whalley’s prepared piano for his Kokopelli from 2017, as well as John Addison’s Spring Dances and Robin Walker’s Her Rapture last year. The result is, as they say, about two hours of neatly entertaining works that show that the recorder has a future as a chamber instrument in modern times; i.e., not just an anachronistic pretty, if soft, sound.

In keeping with more modem aesthetics, the various pieces have eclectic names. For example, Alan Bullard’s Recipes from 1989 seems inspired by a gastronomic journey, beginning with a musical breakfast of coffee and croissants, a light and sort of circus-like tune with folk ancestry. There is something plaintive about the second movement, when a barbecue fire goes out, and here one gets a sort of jazzy moment, and of course nothing could be more English than the finale, entitled “Fish and Chips,” with light flutter-tonguing and a trippy little tune, sounding like it ought to be a sound-track to a silent film. Alan Rawsthorne’s more conventional suite originally dates from 1939 but was rediscovered only in 1992. The opening Sarabande is quite Impressionist, with hints of Ravel, while the Fantasia is a sort of Minimalist throwback to Renaissance times, and the Jig that concludes it is really frothy. Robin Walker’s A Book of Song and Dance from 1994 has a series of movements or songs. The first, for solo recorder, sounds Celtic or perhaps a bit from a Hobbit movie. The remainder do have a plaintive and even nostalgic sound, with a folk element in the background. Walter Leigh’s Air is quite old-fashioned, even perhaps a bit Elizabethan-sounding (the first Elizabeth) in its meandering modal theme. Anthony Gilbert’s Farings, on the other hand, are highly original, using both instruments for sound quality rather than for identifiable tunes. The opening “Mr. Pitfield’s Pibroch” has sounds like a steam whistle, while the “Eighty for William Alwyn” is a sort of Minimalist John Cage. This is followed by the recorder doing what sound like bird imitations (“Arbor Avium Canentium”), and so it goes right up to the final “Chant-au-Clair,” which suddenly turns to a folk round dance above a drone, very Celtic and actually quite the opposite of the remainder of the movements. Turner himself has a four-movement suite, containing a lively waltz and a final manic hornpipe. Contrasts abound between the John Golland Suite with its slightly Neoclassical dances and his New World Dances, which take the recorder into the realm of modem ragtime, blues, and finally a trippy bossa nova. The Whalley work, Kokopelli, named for a famed Hopi figure, uses a prepared piano, where the sound is a bit otherworldly, with a haunting recorder counterpoint. The performance by Turner and Lawson is uniformly excellent, allowing for the blend of the two instruments to complement each other, and even Whalley’s homage to John Cage is quite accessible. If you wish to know how an early instrument can fit into the sound world of contemporary music, this is the disc; entertaining, eclectic, and fully expressive of the possibilities of the recorder and piano. Highly recommended.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978