Fanfare

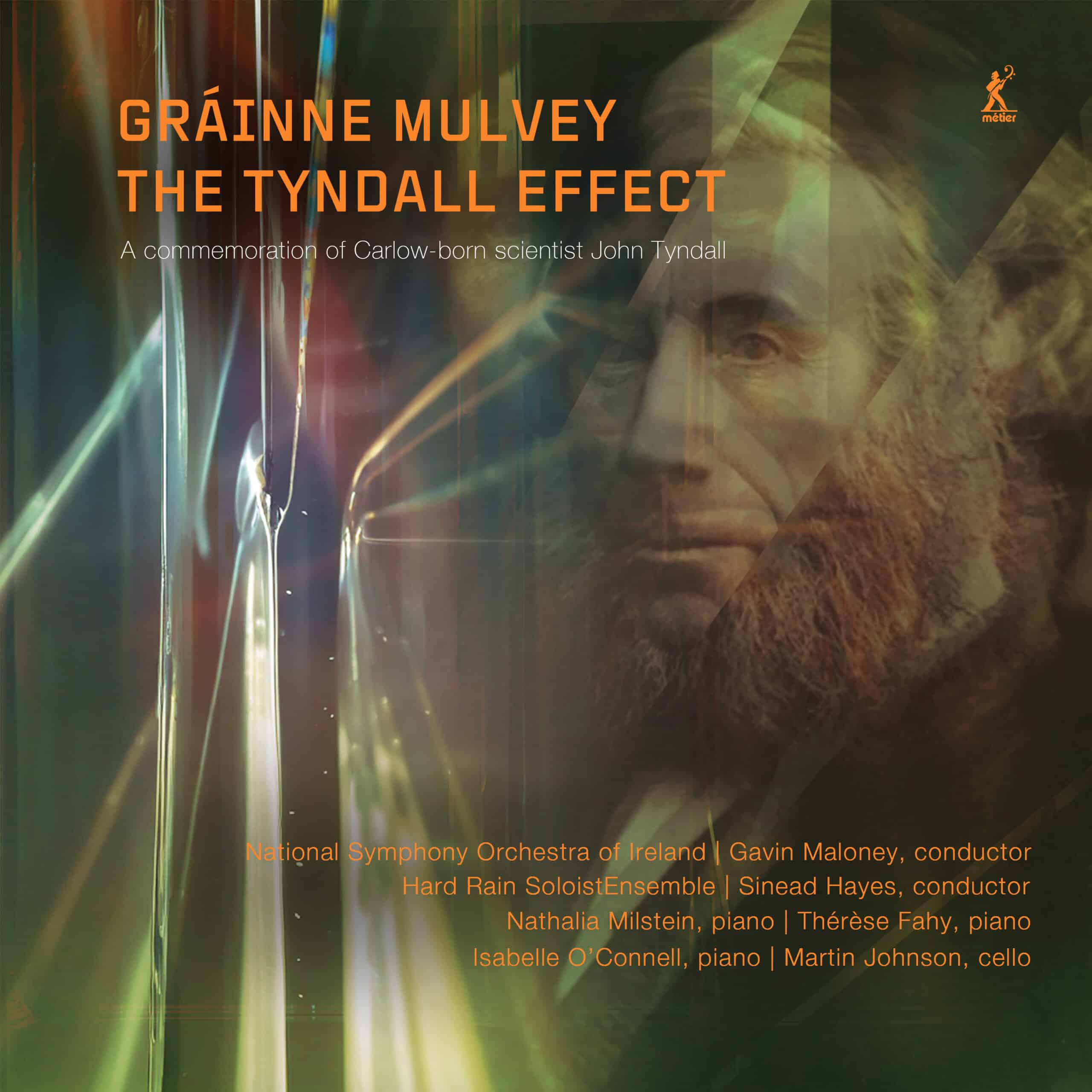

Interestingly, this is not the only recent release from the Divine Art stable where music and physics meet. Edward Cowie’s Rutheford’s Lights is similarly inspired; there is even common ground in the form of the Irish scientist Thomas Preston (1860–1900). Both Preston and Rutherford were fascinated by the diffractions and refractions of light. It was John Tyndall’s lectures on sound and light that inspired Gráinne Mulvey’s wild orchestral piece Diffractions (2014). Vast sound masses and glowering dissonances all characterize the soundscape that is Diffractions, played in absolutely uncompromising fashion here by the National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland under Gavin Maloney. It is only at the very close of the piece that we “hear” bright light (as the general pitch level rises, too), as if something comes into focus. John Tyndall (1820–1893), a devotee of both Faraday and Darwin, had a fascinating life of broad and varied experiences. At one point he studied under Robert Bunsen (he of Bunsen burner fame). Tyndall’s work with light is a major component of a life that encompassed both science and the arts.

The next piece, Interference Patterns of 2014, is for solo piano. Commissioned by the 2015 Dublin International PianoCompetition, it is inspired by Tyndall’s research into diffraction. All three finalists had to play Mulvey’s piece, and the recording we have here is by the winner, Nathalia Milstein. It is easy to hear why she gained the laurels: Her playing is characterized by the understanding of someone who specializes in contemporary music (whether she does so or not). From her icy attacks to melting phrases, the latter angular but shaped like a Bellini melody, Milstein seems to have the complete measure of the piece.

The interconnectedness of all life due to an original generating “ancestor” forms the basis of LUCA. Underlying this, I would posit, is Mulvey’s sonic representation of the beauty within this process. Part of this seems to entail an “unbearable lightness of becoming,” if I may indulge in a misquote. Even when multiphonics from winds are requested, there is only an enhancement of this basic state (all credit is due here to the Hard Rain ensemble players); so it is that the explosions of activity manifest themselves as energy as opposed to emotional, Angst-filled outbursts.

The fine pianist for the 2013 piece Coalescence is Thérèse Fahy. The title refers to a theory of the way that matter absorbs infrared light and emits visible light instead. The theory is not now accepted, but Mulvey took the idea both to honor Tyndall and also as a vehicle for musical process: The almost late-Lisztian diablerie of the pounding of the piano’s very lowest register at the opening is deliberately muddied, only to blossom later into melodic/harmonic material that then is able to inhabit the piano’s complete range. There is an almost Minimalist aspect to the repetitions, but this is dirty Minimalism, gritty and edgy. Insistently repeated treblechords pitted against deep bass activity takes the music to what sounds like the breaking point (manically repeated chords right at the top before a frenzy of glissandos) near the halfway point. It must be mightily satisfying to play. Moving to relative consonance creates a post-apocalypse plateau of (again, relative) calm.

In addition to his scientific activities, Tyndall was known as a mountaineer and as a poet. It is in the latter capacity that he inspired Mulvey’s 2020 piece Sun of Orient Crimson with Excess of Light, itself a line from Tyndall’s poem A Morning on Alp Lusgen. The piano (played by the superb Milstein again) is joined by electronics, consisting of samples of the piano sound, extended electronically. The two “planes” (acoustic piano and electronics) seem to coexist, reacting to each other. Again, though, it is beauty that is the defining factor, here a beauty mirroring that of Tyndall’s poem (the quotation is contextualized in the booklet). I would suggest using headphones to listen to this piece, as that offers a more immersive experience. But however it is heard, this is a fine, inventive work that sustains its 10-minute duration perfectly.

And so we move from the poetic side of Tyndall to the mountaineering one: the Cello Concerto, “Excursions and Ascents” (from 2015, according to her publishers; this is the one work that is not dated in the disc documentation). The title here comes from Tyndall’s 1860 book The Glaciers of the Alps, Being a Narrative of Excursions and Ascents, an Account of the Origin and Phenomena of Glaciers and an Exposition of the Physical Principles to Which They Are Related—a bit of a mouthful. The actual direct inspiration is Tyndall’s illustrations (he was also an expert draftsman). Although performed as one span, the piece is tripartite, and only the first part is programmatic: A solo adventurer, the mountaineer (cellist), is set against the terrain of Nature (orchestra). Certainly, the sense of danger is explicit in the first section. The cellist here, Martin Johnson, is exemplary, while the orchestra constructs myriad colors, particularly in the second panel, which portrays the play of light on ice.

Tyndall’s illustrations of the frozen ice formations of the mer de glace (sea of ice) were apparently most impressive, and it is as if Mulvey sets out to find the special element within them and translate that into sound. In addition to the “glacial” scoring of orchestra, the cello is asked to create some noteworthy, possibly unique, sonorities. An invocation of the icy landscape closes the concerto, in all of its beauty, but in all of its violence too. Nature can be cruel, Mulvey seems to be saying, and that implicit violence brings with it an awesome (in the non-American sense) grandeur.

Gráinne Mulvey is a major composer; these works only confirm that impression. Performances are superb, as is the recording. Recommended.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978