The New Listener

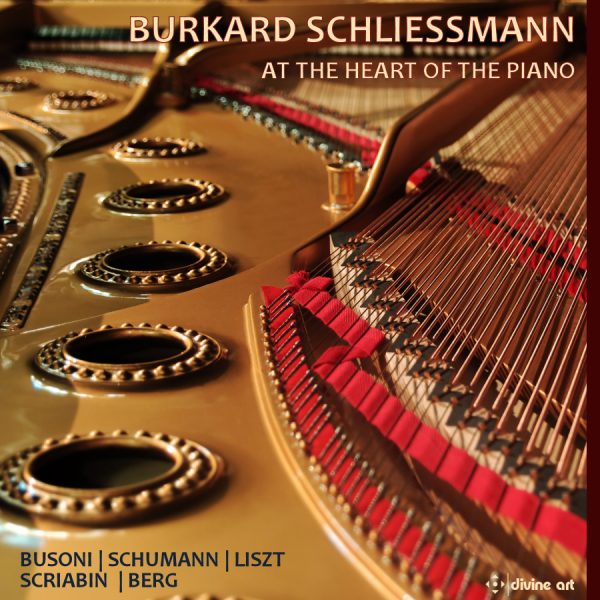

After his 3-CD box set “Chronological Chopin”, which was released in 2016 and was highly acclaimed by the media, Burkard Schliessmann is now presenting a new collection of three CDs on Divine Art, entitled “At the Heart of the Piano”. It is an attempt to approach the piano as an instrument and to wring one’s deepest emotions from it. The title addresses the philosophical question of whether the piano, a first glance the most non-physical of all instruments, consisting largely of wood and metal, which produces a perfect tone by simply pressing a button without physical effort, can convey and express feelings at all, has a heart. Burkard Schliessmann wants to prove this with a very intimate repertoire that means a great deal to him and that brings together various aspects of the piano literature on three CDs). These are exclusively older recordings from the years 1990 (Scriabin), 1994 (Bach/Busoni and Berg), 1999 (Schumann Fantasy and Liszt) and 2000 (Schumann Etudes), which have either never been made or only in a small edition and regionally restricted have appeared, and they shine with new mastering in fresh splendor, so that they are now given the soundworld they deserve. Schliessmann used his own grand piano for all recordings; as a Steinway Artist this is a Steinway Piano D Concert Grand.

Burkard Schliessmann describes himself in his detailed accompanying text for the triple CD, which reveals both facts and personal views on the pieces, as a representative of the “great romantic tradition”. “Technical mastery is of course important, but my interpretations remain essentially intuitive. I don’t think about it and I don’t worry about the implementation of my interpretation.” Although this may certainly be true for the moment of the performance, he is thereby concealing the immense work that he had previously – must have had – with the works. Because it is unmistakable that Schliessmann has thought carefully about what he wants to say with the works and how his personal voice should flow into the notes. In the recordings he shows himself to be a pianist with a strong character who knows how to shape the works according to his ideas and thus tailor them to him. Schliessmann interprets the famous Chaconne in D minor by Johann Sebastian Bach in the virtuoso transcription of Ferruccio Busoni as an attempt to synthesize a baroque and an early modern style of playing. He saves the tempo rubato for special moments in order to maximize expression there.

Schumann is played by Burkard Schliessmann truly appassionato, taking the fantasy in a comparatively more classical way in order to be able to make the symphonic etudes all the more romantic and lively – but this impression may also be partly due to the different reverberation, because here the ambience is more apparent in the etudes (while on the other hand the acoustics flatter the piano sound very clearly and clearly in the other recordings). In both pieces, the pianist uses clear tempo contrasts and rubato for a strong effect, separates individual passages from each other and thus gives the music a vivid, spontaneous, almost improvisational aspect. He plays with the reverberation of the pedal to develop orchestral sonority, although I would argue that he does not see the “symphonic” nature of the etudes in the imitation of certain orchestral instruments, but purely in relation to the differentiated tonal colors of the piano. Schliessmann also experiments with the relationship between the voices, which is clearly evident in variations four and sixteen: the melody remains clear, but always has to assert itself against the seething secondary voices, which makes for extremely exciting listening.

Franz Liszt’s daring Sonata in B minor, which was only recognized late by the public, presents Burkard Schliessmann in a quite aggressive manner; he lets the sound soar to unimagined heights and even takes the liberty to present some highlights violently – probably just like the great virtuoso and showman Liszt might have played it at the time to more deeply polarize the effect. But the fact that this is not Schliessmann’s top priority is shown by the deeply musical development of the themes and their modifications in the course of the piece, whereby he lends the main theme in particular an eerie, oppressive presence. In this way, he succeeds in creating an overall impression of a sophisticated psychological nature that appears to be unified and consistent in itself.

In the works by Alexander Scriabin, Burkard Schliessmann presents a program across all the composer’s creative periods, from the Etudes opp. 2 and 8 and the Préludes op. 11 to the Sonata in F sharp minor op. 23, which shows more individual writing, to the late Dances op. 73 and Préludes op. 74, which appear absolutely independent in the history of music in their spiritual appearance and the complex extended harmony. The flowing, freely presumptuous forms are in the instinctive playing of the pianist, who brings the individual moments to bloom while knowing how to hold the overall form together. The rhythmic polyphony between the hands or their individual voices spurs him on to maintain a high degree of delicacy, even in grandly triumphant passages. Schliessmann pushes the contrasts to extremes and thus shows even the early Scriabin as a modern, progressive composer.

The program closes with Alban Berg’s Sonata op. 1, a showpiece of early modernism and especially of free tonality, which however always reveals tonal relationships. Schliessmann creates a bridge between the second Viennese school and the ecstatic Scriabin, brings out a certain volume in Berg too and allows himself tempo-related liberties in order to underline the density of the polyphony. In this way, this stylistically uniform and yet versatile presentation of Schliessmann’s pianistic work succeeds, which, through the pianist’s highly personal views, brings us closer to masterpieces from different eras in a very human way and invites us to explore them.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

We noticed you're visiting from Latvia. We've updated our prices to Euro for your shopping convenience. Use Pound sterling instead. Dismiss

![🎧 Listen now to the @purcellsingers' first single from their upcoming album, #ASpotlessRose! ➡️ listn.fm/aspotlessrose [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/642752592_1424641949105789_8815810652567824072_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=106&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=1oI-Pe3rGJ4Q7kNvwGTCquZ&_nc_oc=Adnyk0Vd3LjOuhKABRozm7KzfFOFBMD2rkRtxI9QokJxZryQOnhe2pO-WJNFFPudfGR9xVXpYMO5F8ODTa03k2rF&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=a3ey-IZ3dysqq1fkm-ge2g&_nc_tpa=Q5bMBQFBF_WeaipwLi-ek54xChrsl2n-TmLOasm25h-7CsYkaAA4fzNRFj7IsHafg1_AZ7hmITILCVCw7A&oh=00_AfttwPpwe29Bg7Z5SolU5hdODVYPSMugP8AWyxTYKAtNng&oe=69A95641)