Infodad

Composers have many reasons for choosing specific instruments or ensembles for their works, a primary one being the belief that particular instruments or groups are best-suited to communicate whatever a composer wants to express to an audience. In addition, composers who are also performers frequently create works that show their own abilities in the best possible light.

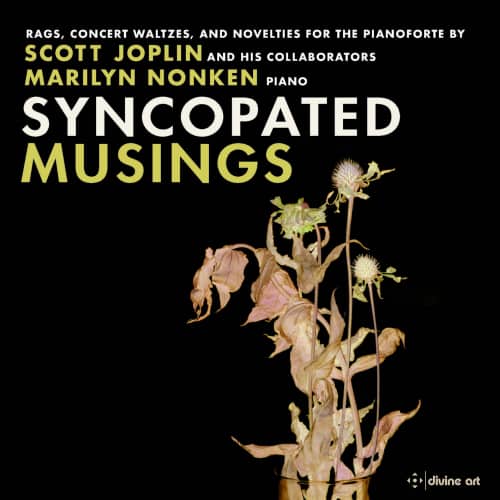

Both of those factors were at play in the early 20th century among creators of the proto-jazz form of ragtime, which is fascinatingly explored on a Divine Art CD by pianist Marilyn Nonken. Interestingly, the best-known ragtime composer, Scott Joplin (1868-1917), played the violin and cornet – and was a singer. He was a capable enough pianist, but the piano was not his primary instrument. Yet it clearly fit what he was trying to do in his many rags, waltzes and other short character pieces. Other composers working on similar music sometimes collaborated with Joplin or sometimes had their works arranged by him, and Nonken’s disc provides an unusual opportunity to hear some of those collaborations and arrangements. Of the 17 works on the CD, nine are by Joplin himself: Eugenia, Stoptime Rag, Magnetic Rag, Binks’ Waltz, Bethena—A Concert Waltz, Pleasant Moments—Ragtime Waltz, Antoinette—March and Two-Step, Solace—A Mexican Serenade, and Reflection Rag—Syncopated Musings.

The eight other pieces combine Joplin’s creativity what that of four other composers: Louis Chauvin (1882-1908), Scott Hayden (1882-1915), Joseph Lamb (1887-1960), and Arthur Marshall (1881-1968). All the pieces here date to the early 20th century, having been written between 1901 and 1917 (the ragtime era was essentially over by 1920); and all share similar sensibilities and a similar approach to melody and rhythm. What Nonken does so well in her performances is to differentiate the individual pieces, giving each its own character and distinctiveness. With most of the works cut from essentially the same mold, this is by no means easy to do; and there is little sense of genuinely different compositional styles among the composers here – everything that is not by Joplin sounds distinctly, well, Joplinesque. But this is by no means a bad thing. It underlines the collaborative nature of this type of music in this time period, and it shows quite well that rags, two-steps, waltzes and marches communicate their sentiments, from joie de vivre to melancholy, very effectively on the piano, which had never been used quite this way before – and which was soon to become the anchor of jazz when that form developed, in part, from works like those heard here.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978