Fanfare

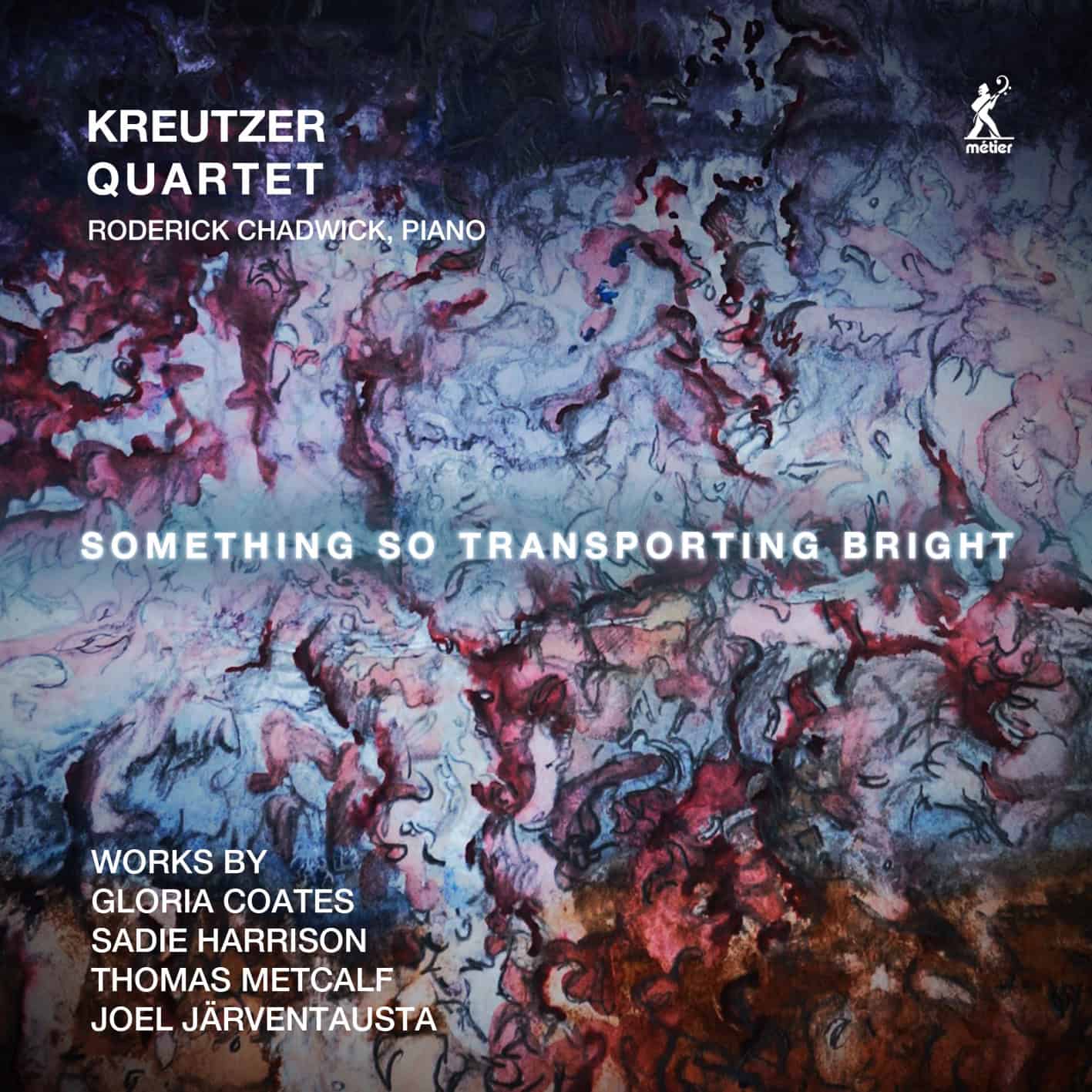

All of the composers on this disc have strong links to Peter Sheppard Skærved and the Kreutzer Quartet; the success of each work in its own individual terms is testament of the fine work of the ensemble in its work with living composers.

This is Thomas Metcalf’s first appearance in the Fanfare Archive. Not to be confused with John Metcalf, Thomas offers here his longest and most introspective work, hewn through difficult personal circumstances and resulting in a work also shot through with “lamentation, rage, anxiety, and obsession.” The idea behind the piece is a question: could a representation of the twisty River Thames be “pixelated” into a sonic representation? A digital graphic of the Thames was used to generate harmonies as well as melodies; a series of cadenzas (solo studies) act as “river-stations.” Each line has its own character here, melding into a fluid whole. The booklet notes speak of discussions about notation during the creation of the work; it would certainly be interesting to see the score. But how wonderful is the river journey here; particularly memorable are the pianissimos, spectacularly sustained. There’s even an emergency services siren in imitation.

Sadie Harrison’s work, 10,000 Black Men Named George: The Multiple Burdens of Injustice was written in an evening as a visceral, angry, and upset response to the murder of George Floyd. It is prayer-like, a meditation upon Martin Luther King, Jr.’s favorite hymn, Precious Lord, Take My Hand. King’s last words were that that hymn be sung at a Mass he was to attend that night (4/4/1968). After an initial transformation into lament, the hymn tune is interspersed with fragments of the famous Shaker hymn Simple Gifts before a final “Lullaby” returns the hymn to its initial state (on viola), inspired by an emotional outpouring by Clinton Harrison. Harrison’s score begins with notated silence (the first two beats of a 3/4 bar as rests, with a fermata above them). The hymn with its characteristic harmonies is heard at a flowing quarter note, superbly voiced here. As the harmonies escalate in complexity, one notices how supremely calibrated they are, and how maskings of the found material never quite obliterate the original. A passage marked “Hope (with simple joy, ever rushed)” finds Neil Heyde’s cello skipping like a post-tonal schoolboy under ever more ecstatic activity; the contrast with the ensuing “Lullaby” means we hear the original hymn reframed (a telescoped Goldberg effect, really). Again, a notated measure of silence (measured, no fermata this time) allows the music to resonate on.

Joel Järventausta makes his Fanfare debut with On Blue. Water, as in Metcalf’s piece, is a prime mover of inspiration here. Inspired also by the works of Turner (particularly that painter’s Studies of Sea), keening gestures inform Järventausta’s own canvas, his music becoming increasingly animated before a sudden hiatus and the emergence of a single line like a glinting on water. Solo lines can take on an almost folk-like slant; the close is inconclusive, the silence stretching out afterwards invitingly.

This is the present performers’ second release of Gloria Coates’s Piano Quintet: a performance in Munich from 2015 appeared on a Naxos release (coupled with Coates’s 10th Symphony, “Drones of Druids on Celtic Ruins”). In the booklet notes, Peter Sheppard Skærved acknowledges the importance of the Naxos recording while also ushering in the idea of a deeper performance, one taken at a remove from that premiere. This is that very later account, recorded live at St John’s, Smith Square, London in October 2018. Coates has half of the quartet tune a quarter-tone away from the rest, resulting in expressive “beats” where there is a notated unison.

The work is inspired by the poetry of Emily Dickinson, each movement headed by her words (the final panel’s title is that of the disc as a whole). The music shimmers, but in an unsettling way; it is timeless, but in a sometimes impatient way. Music of contradictions, therefore, perhaps contradictions enwrapped, or perhaps encoded, within the quarter-tone separation. The performance here is of phenomenal control: of the performers’ instruments, but also of time. Roderick Chadwick is an incredibly musical pianist, and he brings all of that quality to his contribution here; he is also clearly a fine chamber musician, for his playing is completely integrated into the Kreutzer Quartet’s reading. Raymond Tuttle reviewed the Naxos release in Fanfare 42:2; what a privilege for a living composer to have multiple recordings of this challenging piece! The two performances do complement each other; here is a touch more feeling of excitement of living on the edge with the Naxos performance (understandably so, given the newborn status of the music). The Métier recording is a touch more immediate, too; but really, both should be heard.

The documentation is exemplary. Sheppard Skærved’s detailed notes are a model of their kind, while the recordings are superb. This whole release screams fervent advocacy of the new. Unhesitatingly recommended.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978