Fanfare

When Henry James referred to the “complex fate” of being an American, he could have been referring to this collection of chamber works by Rodney Lister. One work, a solo viola piece titled Complicated Grief, captures the drift of the entire program, because the complex fate being addressed revolves around American wars, from the Civil War to the Iraq War. Grief is necessarily part of the aftermath of war, but Lister is looking deeper into the American psyche, pondering how a nation whose self-image is one of peace somehow never escapes the next war.

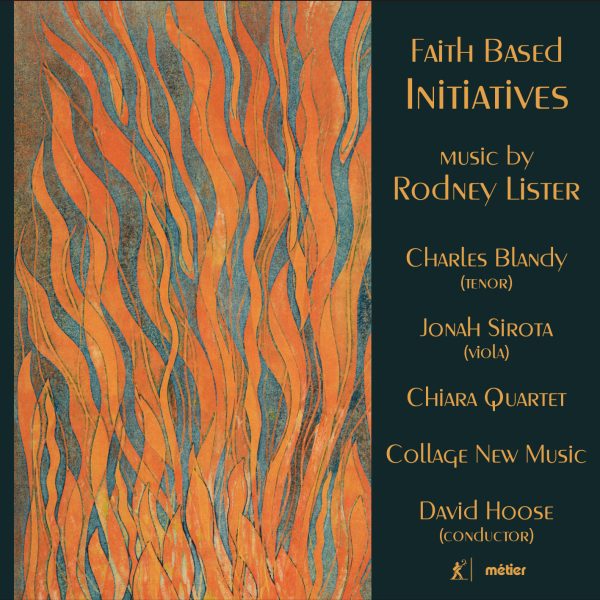

Musically a strain of Americana is strong throughout—the string quartet Faith-Based Initiatives (which gives the album its name) is based on a hymn tune that appears in Charles Ives’s String Quartet No. 1. Lister, himself an articulate writer as well as composer, teacher, and pianist, refers to Ives several times in his program notes. The lineage looking back to Ives wends its way through Copland, Harris, Cowell, Schuman, Rorem, and more. All took American folk roots seriously as an entry point before going on to unfold their own personal styles.

Lister’s quartet comes the closest to being in a direct line with nostalgic Americana. The tune he quotes appears in various hymns; his notes cite the one that begins, “Come, thou font of every blessing.” The melody undergoes inventive development over the score’s nine-minute length and five brief sections, peering into dissonance occasionally but otherwise keeping close at hand the invocation of a hymn. The performance by the Chiara Quartet seems ideal, and the recorded sound is excellent.

At 24 minutes Complicated Grief is an ambitious challenge for an unaccompanied viola piece. Lister takes advantage of the superb technique of the commissioner, Jonah Sirota, founding violist of the Chiara Quartet. The title derives from a clinical psychiatric diagnosis: complicated grief describes an overwhelming state that is paralyzing, making ordinary life impossible. This provides a clue to the intrusion of shocking dissonance, shrieking, and screeching from the viola that makes the forward motion of the music impossible. Sirota expressly wanted Lister not to write an elegy (one of the default modes of the viola), yet there is an elegiac background that makes itself felt in Complicated Grief.

One might easily miss that Lister based his thematic material on pop gospel songs (he calls them “tacky”) that he heard, and secretly loved, growing up in Tennessee; prime examples include I Come to the Garden Alone, How Great Thou Art, and Softly and Tenderly Jesus is Calling. These tunes function as found objects that Lister deconstructs into their constituent elements. There isn’t a direct quotation of any tune, so from the listener’s perspective the hymnal quality of the melodies is lost entirely. By no means does Complicated Grief come across as Americana.

Fortunately, on its own terms the music is arresting and absorbing. As you’d expect, there is a nod to Bach’s unaccompanied Sonatas and Partitas, but not in terms of Baroque gestures. Rather, Lister finds ways, as Bach did, to suggest harmony and counterpoint through double- and triple-stops and the separation of voices. The last technique is particularly striking when Sirota plays one melodic line in the viola’s low register alternating with a second melody higher up. The strength of this piece lies in its continual, bar-to-bar interest and imagination. Sirota gives an altogether virtuoso reading.

The longest work, at 40 minutes, is the settings of 10 poems gathered together as a song cycle for tenor titled Friendly Fire. Lister tells us that he pondered such a work for several decades, back to the Gulf War, before he decided on a rough structure. The work would begin with Allen Tate’s “To the Confederate Dead” and end with Robert Lowell’s “To the Union Dead.” In between would be Herman Melville’s poem on the first battle of Bull Run, “The March into Virginia.” The intention was to insert two shorter war poems on either side of Melville, but eventually Lister found more selections he wanted to set, including a poem by the Iraq War veteran Brian Turner. For accompaniment he chose a small mixed chamber ensemble, represented here by Collage New Music conducted expertly by David Hoose.

As an inveterate reader of American poetry from Whitman onward, I welcome Lister’s project. The core of the thematic material was situated in the long Melville setting. In Ivesian fashion Lister mixed the old patriotic songs that run as a subcurrent in every American’s mind, such as “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean” and “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Fragments of these tunes are deconstructed, making the source essentially unrecognizable, after which they are repeated and varied throughout the entire cycle.

As a result, Friendly Fire is complex, dense, and overall a tough listen; I wasn’t able to follow Lister’s ideas by ear. However, there’s no doubt that this is very skillfully wrought, heartfelt music. Boston is Lister’s milieu, and I think of Friendly Fire as extending the line of American poetry settings by John Harbison. History remains inescapable in New England, and for decades artists have returned in imagination to its bloodied, hallowed ground. Friendly Fire is a deeply conceived work in that lineage. Lyric tenor Charles Blandy copes effortlessly with the music’s atonal vocal line, never losing pitch. I wish, however, that his delivery was more dramatic and varied, in order to make the 10 poets more distinctive and the emotional weather stormier. It was intelligent to arrange the program from the most accessible music to the most challenging. I’d advise absorbing each piece one at a time before taking a deeper dive into the next one. This release deserves a recommendation to general listeners with adventurous ears, but in particular I think that anyone fascinated by Ives, American history, and our complex fate will find the music a rewarding experience.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978