Fanfare

Rodney Lister has had a handful of his works reviewed in these pages, most notably to date an Arsis CD that was favorably covered in successive issues by Paul Ingram (28:6) and John Story (29:1). Since few biographical details were included in these, I’ll mention that he was born in 1951, received his early musical training at the Blair School of Music (Nashville, TN), and attended the New England Conservatory of Music for his BM degree. From there he went on to graduate school at Brandeis University, where he was awarded his Master of Fine Arts degree in 1977 and his DM in 2000. His composition teachers included Peter Maxwell Davies, Donald Martino, Harold Shapero, Arthur Berger, and Virgil Thomson, and he also became an accomplished pianist, working with Enid Katahn, David Hagan, Robert Helps, and Patricia Zander. His music has been widely performed by many notable musicians and ensembles, among which are the Fires of London (a new music group that Maxwell Davies co-directed) and individual performers including Michael Finnissy, JoelSmirnoff, and Phyllis Curtin. He has received commissions, grants, and fellowships from the Berkshire Music Center, the Fromm Foundation, and the Koussevitzky Music Foundation, among others. He is currently on the composition and theory faculty of Boston University, and directs its new music ensemble, Time’s Arrow.

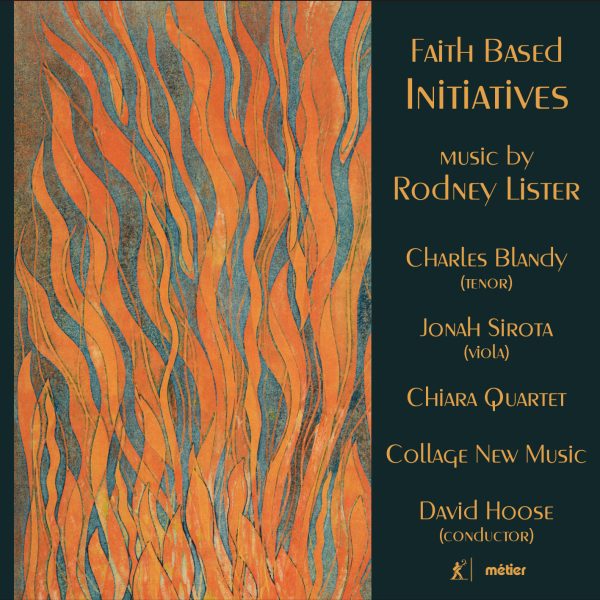

The title of the CD under review is Faith-Based Initiatives (purloined also for the title of this feature), after the first work presented, itself drawn from the world of politics and, in the composer’s words, a “reference to the governmental program which is one of the means by which the Bush administration attempted to obliterate the separation of church and state. In this sense, the logic of the piece is an encoding of the process of taking something putatively simple and pure and turning it into something grotesque.” This five-section work is based on the well-known hymn “Come, Thou Font of Every Blessing,” also notably used by Charles Ives in his String Quartet No. 1. The most obvious references to the tune come in the odd-numbered movements, while the other two make obeisance to it much more obliquely. Indeed, the opening of the piece contains a complete statement of the hymn, albeit subtly reharmonized. After this initial iteration, however, the traditional harmonies and melodic contours are transformed into something rather unrecognizable as to their source. Irregular figures in some of the instruments are punctuated by pizzicato in highly syncopated fashion in the other instruments, a very effective device. The tune does return from time to time in recognizable form, although never in its original overt tonality until the very end of the work. The Chiara Quartet has crafted a seemingly definitive rendition of the work.

Lasting almost a half hour, Complicated Grief forms one of the most extended works for solo viola I can think of. Its title was brought to the composer’s mind by a radio program he heard and refers to a type of grief so debilitating that it inhibits quotidian activity. While this sort of grief didn’t overcome Lister, who had lost his father around the time he was beginning the work, the term caused him to reflect on his father and his passing. Like its predecessor in this recital, the composer has drawn material from a number of hymns, this time using primarily deconstructed fragments of them. The work’s quiet and somber beginning is rudely interrupted a minute into its first movement (of three), producing a jarring, albeit effective, diversion. Other sorts of tempestuous outbursts continue to interrupt the soothing lines, the former utilizing glissandos, sul ponticello, harmonics, or other special effects, and often embroiled in immediate proximity to each other. Lister proves himself a master, not only in the flow of his musical ideas, but also in exploring the manifold colors that this alto member of the string family can produce. The work ends with a kind of quodlibet comprising a string of unrelated tunes. Violists looking for an alternative to Britten’s oft-performed Lachrymae would do well to investigate this challenging yet rewarding work. Violist Jonah Sirota, who requested the work from Lister and a member of the Chiara Quartet, provides a breathtaking performance.

Friendly Fire remembers events in various bellicose conflicts ranging from the Civil War up through that in Iraq. It was inspired by Lister’s having watched Ken Burns’s excellent and gripping Civil War film, which coincidentally I’d watched not more than two months prior to my writing these words. Various aspects of these conflicts are suggested even by the titles of the 10 movements, some of which include “Ode to the Confederate Dead,” The Fury of Aerial Bombardment,” “Women, Children, Cows, Cats,” and “A Box Comes Home.” It lasts almost 40 minutes, and the composer chose texts that connected these events across time, albeit in non-chronological order (the last movement is entitled “For the Union Dead,” forming a bookend to the first). One unifying device the composer employs in poetry by such diverse poets as Herman Melville, John Ciardi, and Robert Lowell, is the declarative way the text is set. Tenor Charles Blandy with the support of conductor David Hoose and the Collage New Music of the New England Conservatory in Boston, superbly capture the pathos and anguish of the texts before them. Blandy must have an exceptional ear in order to hit the almost-atonal lines he must contend with so squarely on pitch. He must also be possessed of more than average endurance, given the almost continual flow of sounds he is required to produce. The ensemble is masterfully held together by conductor Hoose, no small feat given the music’s seeming absence of metrical regularity. The hornist in this ensemble has an especially demanding part, and so I single him or her out for extra praise.

This is a challenging work to experience, both on the grounds of the poems and Lister’s setting of them, but there are plenty of rewards awaiting the listener who approaches the work with an open mind. Particularly gripping was his setting of Randall Jarrell’s poem, Losses, a first-hand account of the poet’s war experiences. The ghost of Ives hovers over Melville’s “March into Virginia,” to the point of containing a very Ivesian martial tune, and a mirroring of his use of a concatenation of civil war tunes akin to those the iconic American composer employs in his In Flanders Field. In all three of the works presented here, Lister proves he has a distinctive and secure compositional voice, one that is one well worth exploring by those who are seeking new and arresting music. For that select group, this disc receives my firm recommendation.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978