Infodad

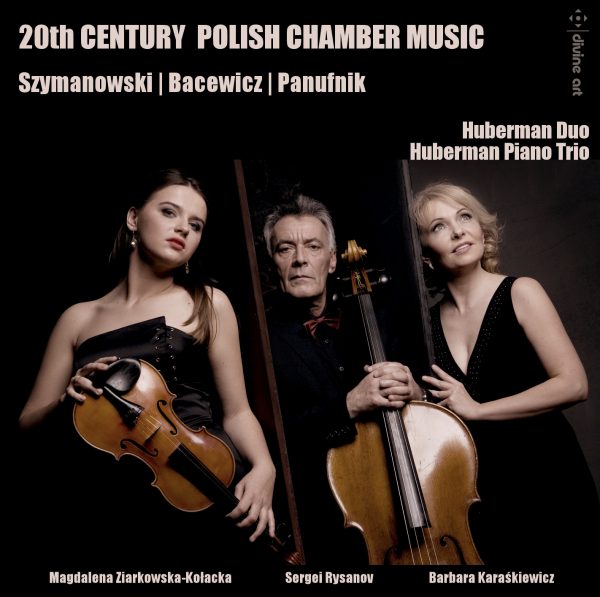

Listeners can hear a new Divine Art recording featuring chamber works by three prominent Polish composers, performed by two or all three members of the Huberman Piano Trio. The best-known composer here is Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937), represented by his D Minor Sonata for Violin and Piano of 1904 – a work as youthful in its way as Mozart’s violin concertos are in theirs. The Szymanowski way in this earliest of his chamber compositions is clearly in the process of abandoning Romanticism and almost escaping traditional tonality. Cast in the traditional three movements (the second combining slow-movement and Scherzo elements), the sonata is front-weighted, the opening Allegro moderato full of violin expressiveness that never quite allows lyricism to enter the sound world. However, in the Andantino tranquillo e dolce, which begins in much the same mood in which the first movement concludes, there is a certain amount of genuine tranquility and perhaps even sweetness – although the chromaticism gives the material an edge, as do the pizzicato passages that are well-contrasted in this recording with the legato ones. The finale has some characteristics of perpetuum mobile and a variety of nervous-sounding tremolo effects that highlight the violin’s thorough dominance of the material – the piano is distinctly subsidiary in this sonata, although it often helps ground the violin, allowing it to produce flights of fancy.

Three decades separate this sonata from the 1934 Piano Trio, Op. 1 by Andrzrej Panufnik (1914-1991), but this trio too is a work of its composer’s youth. Panufnik revised the work in 1977, and the Huberman Piano Trio uses that version, but the compositional explorations of a young man still come through clearly. The trio takes some of the elements of Szymanowski’s approach a good deal further, lying easily within what had by the 1930s become standard forms of modernism. But it actually seems more comfortable with old-style Romanticism than Szymanowski does in his sonata, as if the clear break from that tradition is now so firmly ensconced in music that it is acceptable to return to it to produce a certain number of effects. Panufnik’s trio is also strongly influenced by jazz, which throughout the 1920s and into the 1930s was such a significant element of classical composition. The piano riffs in the Presto finale, for example, show the jazz influence quite clearly, as does the trio’s overall rhythmic fluidity, which sometimes makes the music sound improvisational even though there is nothing aleatoric in it. The flourish at the work’s very end seems entirely in character for the piece as a whole.

Also on this well-played CD is the highly interesting Sonata No. 4 for Violin and Piano by Grażyna Bacewīcz (1909-1969). This is a four-movement work from 1949 that incorporates mid-20th-century notions of tonality, rhythm, and instrumental contrast, but does so in a context that, like that of Panufnik’s trio, is not averse to looking back at the Romantic era. That is especially evident in the second movement, an Andante ma non troppo that sounds both emotional and expansive in this recording and that is then very nicely contrasted with the Scherzo: Molto vivo that follows. That movement is almost Mendelssohnian in its lightness and scurrying, although scarcely so in its harmonic palette. The finale of this sonata balances the first movement effectively – this is the only work on the CD that does not have a dominant opening movement – and the concluding movement’s Con passione marking is taken seriously here, lending the finish a degree of intensity that would not be out of place in Romanticism, even though the actual sound of the material is very much of its time.

Whether interested in Polish music, 20th-century chamber pieces or simply in very fine small-ensemble playing, listeners will find much to enjoy here, including a presentation in which violin, cello and piano are all handled with a very high level of skill and a great deal of involvement in the music.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978