Planet Hugill

A metaphysical meditation on the art of transformation, White’s latest opera is a dazzling tour-de-force for just two performers

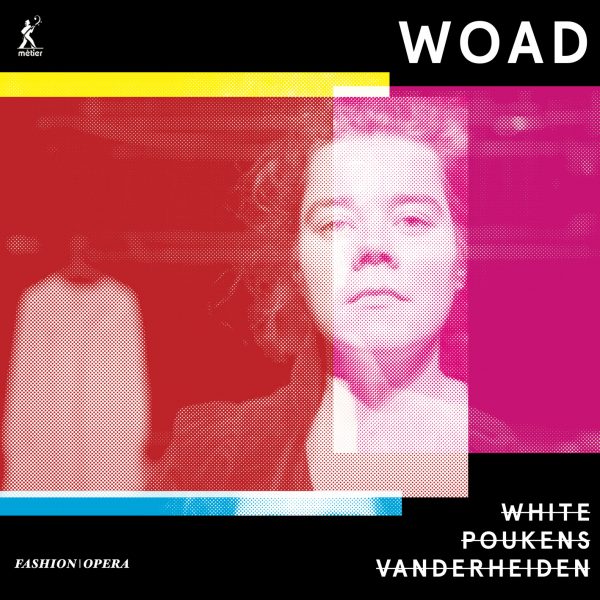

Alastair White’s Woad is the third in his fashion|opera cycle, following Wear and Rune.

In the medieval Scottish Borders, a young boy is bewitched – into the form of an ape, an adder, a speck of dust. But is it his shape that twists and churns, or that of the world around him? These are the questions considered by Woad. The piece is inspired by the Scottish Border ballad Tam Lin a tale as much about the idea of transformation whilst retaining one’s true qualities. It is this aspect of the ballad that White has picked up on. In dramatising Tam Lin, he boils the idea of opera down to its essentials, just a voice and an instrument.

Soprano Kelly Poukens does not play a particular character, instead White’s seven scenes (the libretto is his own) are a meditation on different aspects of transformation.

He uses the story to contemplate worlds of co-incident possibilities, and his texts for the seven scenes are profoundly poetic in their own right. The final scene, ‘The Transformation of Tam Lin‘ features a text that is laid out in a way that makes it a work of art in its own right; the multiple columns of White’s text reflecting the multiple possibilities of his imagined universe.

His writing for both soprano and saxophone is challenging, and often Poukens’ vocal line is highly instrumental, the two weaving together like two instruments. Musically the work is dazzling in that way that White mines the combination of the two in so many different ways. Throughout the writing is complex and challenging, yet in each of the scenes White reflects musically on different aspects of the story. If you are interested, you can analyse the various compositional strategies that White uses, but you can also stand back and simply enjoy the sheer variety on offer here.

Poukens and Vanderheiden impress with their performances, both the technical grasp of the music and their sense of White’s idiom (Poukens performed in White’s two previous operas). If I have a moan, it is the single point that to follow the text you very definitely need the printed libretto in front of you.

Technically complex, dazzling in its confidence at writing for just soprano and saxophone, philosophically deep this is a work that eludes definition. Almost like Tam Lin himself, Woad slips through the fingers, is it an opera, a song-cycle, a cantata, a piece of music theatre, all four or none? So, whilst White is ostensibly meditating on the art of transformation via a mythical man who was transformed by turns into a variety of different forms, he is also contemplating what it is to write opera in the 21st century. And the work becomes particularly apt as it was recorded in January 2021 (and performed live later that year), so a work for just two performers fits very much into the ethos of boiling down performance to its essentials that has happened since March 2020. In a way, White’s Woad is a 21st century metaphysical twin to Judith Weir’s King Harald’s Saga, her ten minute grand opera performed by a single soprano.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

![🎧 Listen now to the @purcellsingers' first single from their upcoming album, #ASpotlessRose! ➡️ listn.fm/aspotlessrose [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/642752592_1424641949105789_8815810652567824072_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=106&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=aY1NGfNpOoYQ7kNvwGEkRhR&_nc_oc=AdnVMkFfl73eIpyXf4AQvx7wVfy0l6iYiWX1xZ1czHURCUKG2_ilwXDyqQAkVlnjrPk&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=HuiV8kkP6XC3mCQB_B7vjg&_nc_tpa=Q5bMBQFrtg9Efcb4WqRbQ89UMtMK-ydVU7_pnVa46nfNeusGrMatfoYlByFbFoZkCH4AMV3w0LOkzSM1jw&oh=00_AfzlGFx-tNYAoYXg40zg6x251arrcQ5GibnQVnGtxkedLA&oe=69AFEDC1)