Fanfare

I’ve only had the pleasure of reviewing a work or two by Naji Hakim previous to this release, having done so for his Rhapsody for Organ eight-hands/four-feet back in 41:4, as well as a short Christmas piece. Those were terrific works, so I was pleasantly surprised to receive a full disc of his music for the present review cycle. Hakim is of Lebanese birth (1955), having studied organ with Jean Langlais, harmony with Roger Boutry, fugue with Marcel Bitsch, analysis with Jacques Casterede, and orchestration with Serge Nigg. I find it interesting that each of these teachers is (or was) a gifted composer. It is no surprise, either, that Hakim’s music is characterized by a pronounced French style.

The opening Salve Regina for violin and organ is prefaced by a tenor’s rendition of the original plain song upon which Hakim’s setting is based. While interesting, it is so different from Hakim’s style that it seems anomalous to me. Never mind, though, because the following work was so supremely beautiful that I found myself reveling in its beauty. The subsequent Capriccio is as lively as the Salve was reflective, and could almost be a movement from a concerto for violin and organ. Its themes are not as profound as those in the preceding work, and some auditors might even consider them a little trite. I found the piece to be a good bit of fun, and most listeners will enjoy it if they don’t take it too seriously. The Gallic influence cannot be missed here, although in this work it leans towards the lighter style of Bitsch than the more serious aesthetic of Langlais (whose influence in Salve is pronounced). Violinist Benedict Holland plays with confidence and accuracy in these two works, but I found myself wishing that he had been a little more closely miked. The organ overwhelms him in several places, and he needs to be more prominent even in the places where he can be heard.

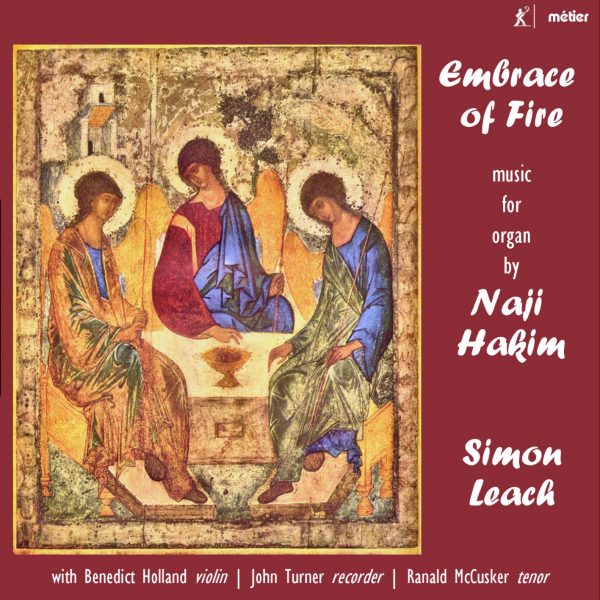

The Embrace of Fire is a three-movement organ work with sung plainsong introductions preceding the first and third movements. For some reason, these did not seem to be out of place as their inclusion was in Salve Regina. This exciting and virtuosic work was awarded first prize in the Anton Heiller Memorial Competition for Organ Compositions in Collegedale, Tennessee. Its title was inspired by the icon of the Trinity by Roublon, and each movement is preceded by a quotation from Scripture. The serious tone of the work is miles apart from the almost frivolous Capriccio, and the piece, which amounts to an organ symphony, will surely appeal to those who are fans of the music of, for example, Toumemire or Dupre. Hakim, like many of his French predecessors, has precisely specified the regis¬tration of his organ music, and it is full of colors that shimmer at times and overwhelm at others.

Toccata on the Introit for the Feast of Epiphany was premiered in 2016 by Simon Leach, the organist featured on this disc. Toccatas in general show off the skills of an organist, and this one is no exception, giving Leach plenty to do, with the technical wizardry punctuating the traditional plainsong melody. Diptych must be one of the very few works that combines a recorder with an organ. Since the former could be covered even by the softer stops of the latter, a composer must take great care in balance between these two instruments. So, needless to say, Hakim doesn’t exactly call for the contrebombarde stop in this work. It is cast in two movements, a gently flowing “Cantilene” based on a popular melody attributed to Pergolesi, and a spritely “Humoresque” employing an altered rondo form and the typical sonorities of the txistu, a three-holed Basque flute. (The things one learns from reviewing for Fanfare….)

Concluding the recital is a triptych, Hommage à Igor Stravinsky, a work also inspired by Gregorian chant (something not typically associated with the great Russian master, I might add, although Threni and a few other works might show some influence). This is, by a good measure, the most austere work on the concert, with dissonances—even tone clusters—sprinkled generously throughout. Hakim employs much use of antiphonal registration, and the rhythmic energy of the piece is the only parameter that shows any influence from the person to whom he is paying homage. The style of this work is quite original and sounds much less French than any of the other works heard here, although Hakim’s musical upbringing can scarcely be completely suppressed, and the French influence sneaks back in for the final movement of the piece, which ends on a triumphant D-Major chord.

Simon Leach is clearly a master of his instrument. His playing is nothing short of brilliant as he combines technical precision with varied articulation, all the while allowing the music to breathe. It is always a delight to hear new works in such definitive performances, and I would think that Naji Hakim must be very pleased with this presentation of his music. Highly recommended to organ enthusiasts and others interested in the music of our time.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978