Diapason

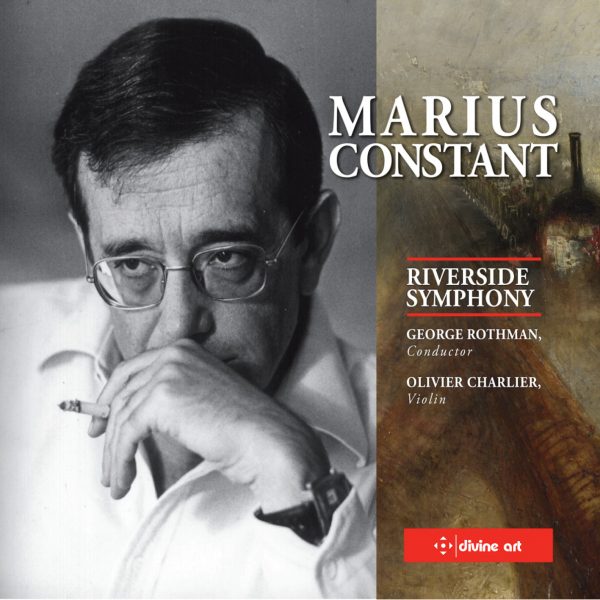

Opening a window to an inventive, playful and seductive style of modernity, the compositions of Marius Constant breathed a breath of poetry and freedom in the rather dry universe of the avant-garde at the turn of the 1960s. At the same time musical director of Roland Petit’s ballets, initiator of Ensemble Ars Nova (whose excellence could rival that of the Domaine Musical), and co-founder of France Musique, Constant continued to compose, to teach and to work in his other roles before rather disappearing from public view as when he left his native Romania.

His quality is rare: the pastel colors and the sfumato of Turner (1961) which had enchanted the public of the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence in 1961 are rediscovered here with the same amazement. The evolution of its discourse, without being simplistic, is always organic, and therefore easy to grasp even in its contrasting reversals, its ruptures, its languor. If perhaps one can see a connection with the Pieces for orchestra op. 10 by Webern for the elegance of the impressions, we have a greater sense of Dutilleux’s Tout un monde lointain (1969). In short, a masterpiece which, if the programs of French orchestras were concerned with reconciling their audiences with the music of the second half of the twentieth century, would abolish prejudices – even without the absolute perfection of the Riverside Symphony.

More massive in color as in their structure are the four movements of Brevissima (1992). This condensed symphony deserves much performance for the height of its qualities. Composed for Patrice Fontanarosa (who premiered it in 1981 and recorded it for Cybelia), the violin concerto 103 regards dans l’eau is more in tune with the modernity of its time, except that it sounds better thanks to the infallible meaning which Constant provides, for the associations of impressions in the fusion of the parts as well as in the contrasting opposition. Omnipresent and abundant, the solo part, never overshadowed by the orchestra, is a work of extremely brilliant, ostentatious and sometimes verbose virtuosity. If the crystalline introduction and the poignant finale concentrate the interest, this thirty-minute fresco does not make you regret the ideal performance of Olivier Charlier.

(translated from the original French)

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978