Infodad

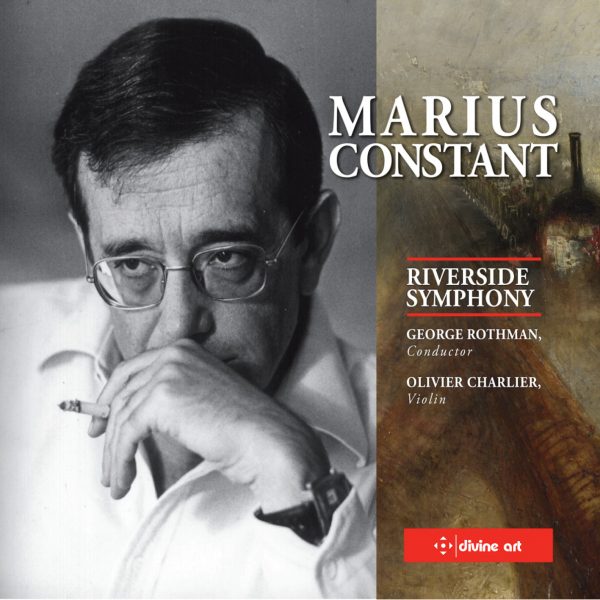

The symphony orchestra remains the ne plus ultra for tonal color and communicative potential using the widest variety of sound worlds and combinations. As a result, composers continue to search for new ways to use symphonic forces for a large variety of expressive purposes – and to make a great number of points with, to and for listeners. Those points are not necessarily made in traditional concert halls: some very fine and classically trained composers are known primarily for their contributions to popular culture – Dimitri Tiomkin and Bernard Herrmann for films, for example, and Marius Constant (1925-2004) for a single work for television: the theme for The Twilight Zone. But there is considerably more to Constant than that: his ballets still garner occasional performances, and his symphonic works, on the basis of a new Divine Art release, are certainly worth the occasional hearing.

The three pieces performed by the Riverside Symphony under George Rothman have very different intentions. Turner (1961), as its title is intended to indicate, is inspired by the paintings of J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851). The first movement reacts to Rain, Steam and Speed (1844) with a suitably atmospheric portrayal; the second to Self-Portrait (1799) with a focus on drama; and the third to works including Windsor Castle from the Thames (1805) and Windsor Castle from the River (c. 1807) in a style mixing the impressionistic with the suitably magisterial. Listeners unfamiliar with the specific Turner works to which Constant is reacting will hear well-proportioned music whose connections to particular topics are less than obvious.

Brevissima (1992) is a more-interesting work: an entire four-movement symphony boiled down to a mere 10 minutes. The rather scattered-sounding Scherzo, placed second, is the most unusual movement; the concluding Passacaglia funèbre is the most intriguingly structured. The piece is, in truth, somewhat too compressed, hinting at the symphonic rather than actively seeking it. But, like Constant’s music in general, it shows a fine command of orchestral forces.

The longest work on this disc is a four-movement violin concerto from 1981 called 103 Regards dans l’eau (“103 Poetic Celebrations of Water”), featuring violinist Olivier Charlier. Two slow movements frame two faster ones here, the violin making its primary points mainly in its top register and the work as a whole coming across as rather self-indulgent and self-consciously “modern” in sound. It is an interesting piece but not a particularly engaging one, although, again, the writing for orchestra – and for the solo instrument – is impressively self-assured. The CD offers more insight into the composer than audio recordings usually do, because it also contains video material: a discussion of the music with Rothman and archival footage of Constant, with all the video formatted for computer playback. This additional quarter-hour of material certainly broadens the scope of the almost-hour-long audio portion of the disc, although really, the music needs to speak for itself rather than through the video – and it does so, telling listeners that Constant was a skilled if perhaps not highly innovative composer who handled orchestration with considerable ability even though the underlying ideas and sounds of the works heard here are not particularly original.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978