Fanfare

Back in Fanfare 38:1, I thoroughly enjoyed reviewing a disc of piano music by Marcus Blunt performed by Murray McLachlan, the soloist in this performance of Blunt’s Piano Concerto. Blunt was born in 1947 in Birmingham, United Kingdom and studied composition in Wales (University College, Aberystwyth). The pioneering record company Metier is right to take up his cause: His music is both approachable and rewarding on a deeper level—music to live with, rather than to ex¬perience once and file away forever, in other words.

The Piano Concerto was written between 1992 and 1995 (Blunt had attempted the form at the age of 17, which perhaps might be classed as “juvenilia”). It is a substantial work in terms of its in¬tensity and serious demeanor; it actually lasts some 27 minutes. Blunt could not ask for a more sensitive interpreter than McLachlan, who finds real beauty in the gentle arpeggios of the first movement. Blunt uses brass to bring in an ominous aspect. His scoring is masterly, the soloist never in danger of being submerged by the orchestra. Stylistically, one might point to a mix of Tippett and Scriabin with some Havergal Brian thrown in, but to do so is merely to introduce useful markers for the listener. Blunt’s voice is more than the meeting of these giants; it has a flavor all of its own. McLachlan’s playing throughout is perfectly considered and confident, as if he has spent years living with the score. The central Largo explores a world in which less is more; individual notes can appear as points of starlight, connected to sounds around them by the thinnest of threads and supported by gossamer strings. This is a fascinating sound world, one that contains within it the impression of eternal invention. The finale exemplifies this trait to perfection, with themes naturally morphing into others while references to previous movements act to create a web of allusions. The piano part throughout is not virtuosic; its voice is sometimes more of an elected spokesperson for the orchestra rather than a spotlit soloist. The conclusion of the piece is bleak as well as dramatic. Superb.

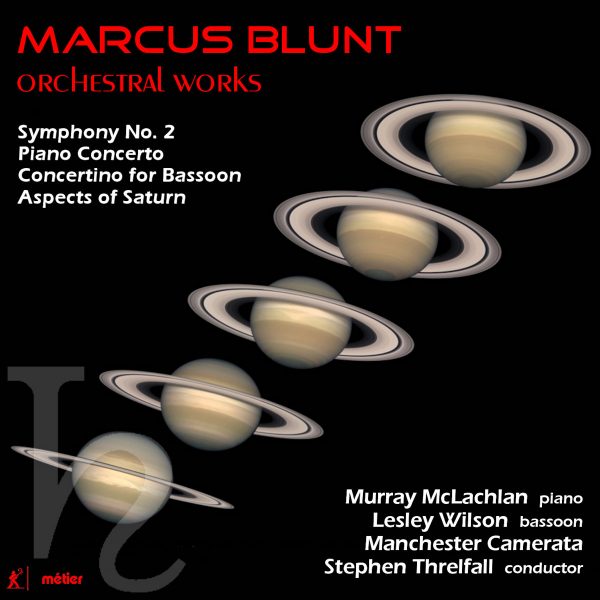

The score of Aspects of Saturn for string orchestra is prefaced by two poetic quotations, one by Keats (from “Hyperion”), the other from Virgil’s Eclogues. The disc cover includes multiple images of Saturn as well as, in the bottom left comer, Saturn’s glyph (in the version without the cross-through towards the top of the vertical stroke). The growth of the music from quiet and dark to ecstasy, as well as the choice of literary quotations, reflects the contradictory nature of Saturn’s own qualities: limitation/ambition, for example. The work itself is glorious. Less than seven minutes in duration, one rather wishes it were longer, and yet Blunt says all he needs to in that time: a temporal contradiction, perhaps, for the Father of Time himself. Wonderfully imaginative from concept through to realization, and presented here in miraculous beauty by the Manchester Camerata, this is one work that deserves more exposure.

After those Saturn energies, perhaps we move to Jupiter for the jovial opening of the Bassoon Concertino (2016, a version with string orchestra replacing the piano of the 1989 piece Lorenzo the Much-Travel’d Clown with one added movement, the arrangement of Scotch Song for unaccompanied bassoon of 1984 as “Aria”). The piece is cast in five movements. That “Aria” is most affecting, and Lesley Wilson plays it beautifully, capturing the cantabile mood perfectly, just as she finds joy in the more active moments. Perhaps it is the more ruminative moments of this piece that linger longest in the memory, as the “elegy” fourth movement is superbly emotional. Wilson plays the cadenza at the close of this fourth movement with huge character and confidence.

Finally, we have the Second Symphony of 2002, an orchestrally expanded version of the 1991 piece The Throstle-Nest in Spring (a work which was scored for the same combination as Schubert’s Octet). The original five movements are honed down to four; the orchestra used is a modest one, with no tuba, trombones, or percussion apart from timpani, yet it is capable of plenty of emotional punch. Bright and breezy for most of its time, the first movement laudably wastes not a single note. Symphonically, Blunt knows what he wants to say and says it with a refreshing economy of means. A tender Andante, beautifully realized here with the Manchester Camerata strings glowing through¬out, holds a climax at the core whose power comes through Blunt’s harmony rather than the dynamics. This movement also holds some wonderfully controlled and balanced brass contributions. Blunt cleverly gives an impression of expanding out in his third movement while keeping the pulse the same; again, those dark, treacly harmonies, here on brass, speak of the depths Blunt’s music is capable of plumbing. From the resignation of the movement’s close emerges a spirit of play in the woodwind as the brief finale gets under way (the whole symphony only lasts some 17 minutes). The use of inter-movement thematic relationships binds the whole into a coherent structure, while Blunt’s harmonies help to evoke a feeling of continual exploration and searching.

The recording, from the concert hall of the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester (a beautiful acoustic: I have played there myself many times) is superb. This is a tremendous success from all viewpoints.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

We noticed you're visiting from Latvia. We've updated our prices to Euro for your shopping convenience. Use Pound sterling instead. Dismiss