Fanfare

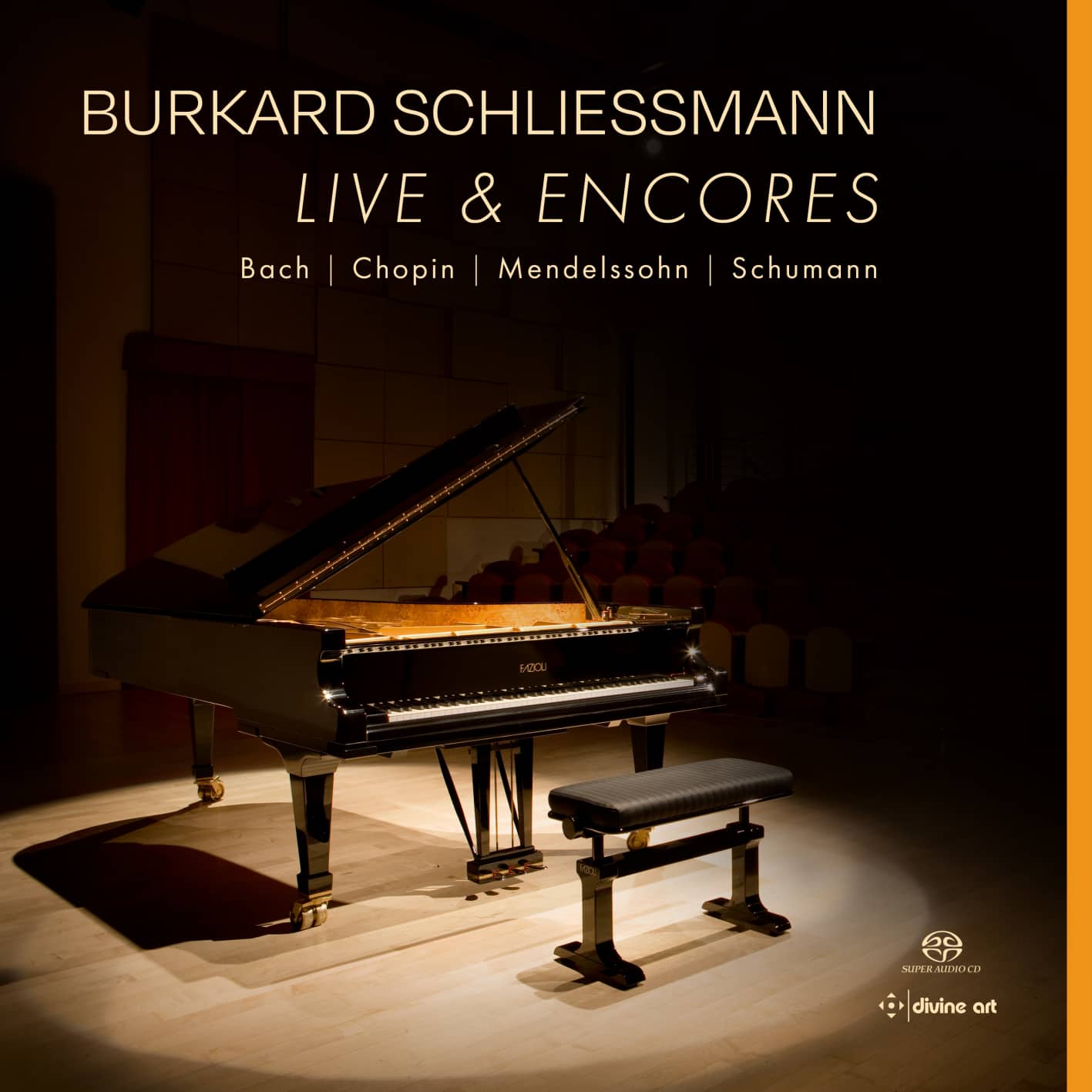

In Fanfare’s Mar/Apr 2015 issue (38:4), I interviewed Burkard Schliessmann, mainly in connection with his then new SACD Divine Art album of works by J. S. Bach. Among a couple of other items, that disc contained the Partita No. 2, the Italian Concerto, and the Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue, all three of which are duplicated here on this newly released two-disc Divine Art SACD set. I hasten to add, however, that these are not the same performances. It’s impossible for them to be since they were recorded as recently as April 3–5, 2023 at the Fazioli Concert Hall in Sacile, Italy, on Schliessmann’s personally owned Fazioli F278 concert grand.

These works are near and dear to the pianist’s heart and are part of his core repertoire, so it’s only natural that he would want to go on record with them again. The same may be said of Schumann’s Fantasie, which was included in Burkard’s three-disc album, only released in September, 2021, but remastered from a much earlier recording that had been previously issued on the Bayer label. The Divine Art three-CD set, titled At the Heart of the Piano, received several glowing reviews in Fanfare 45:3.

As far as I can tell, this is Schliessmann’s first time on record with Mendelssohn’s Variations sérieuses, and while I don’t believe that the pianist has recorded Schumann’s Carnaval complete, he does give us here the ninth movement, titled “Chopin,” as one of his two encore pieces. And then, for his second encore, he offers a performance of Chopin’s Waltz in CT Minor, which I do believe he has recorded previously.

Schliessmann’s new set at hand begins with Bach’s C-Minor Partita, and I have to admit that the pianist’s way with Bach is definitely his own, yet one that I find quite captivating. Take, for example, the manner in which he addresses the shift in tempo, texture, and musical content at the point in the score marked Andante that follows the Grave Adagio introduction to the piece. His left-hand “walking bass” eighth notes are clearly articulated with a staccato touch, but not nearly with the martelé aggressiveness of, say, Glenn Gould’s staccato. Meanwhile, Schliessmann’s right hand remains remarkably free to follow the clues and bring out the notes that constitute the melody as it plays hide and seek among the mirrored maze of Bach’s contrapuntal crossword puzzle. The melody notes are not necessarily contiguous in all of the running passagework. Somewhere in there is a singable line, because Bach always sings, and he teases the player’s fingers to find the song in the line and the listener’s ears to hear it. Schliessmann has a keen ear for those notes, and his fingers know how to make the line sing.

Next on the disc is Bach’s Italian Concerto, which, being a piece for solo harpsichord, is not a concerto as we normally define the term. Nor is there anything one can point to that identifies it as Italian. In fact, the original title of the piece was Concerto in the Italian Taste. The Italian Concerto plus the French Overture together comprise Book II of Bach’s Clavier-Übung, the shortest of the three books in which the composer published what he considered to be his most important keyboard works.

With due apologies to all pianists, I will say that the Italian Concerto is one of those pieces specifically designed for a two-manual harpsichord that cannot be fully realized as intended on the piano. Bach achieves the concertino-vs.-ripieno “concerto” effect by juxtaposing passages of lighter and softer textures against fuller and louder ones. But he also designates the lighter—i.e., solo or concertino—passages to be played on the second manual, which through the use of different stops can be made to sound like a completely different instrument.

The piano can accomplish the first part of this, differentiating the textures through dynamics and touch, which I have to say Schliessmann is very, very good at, but not even he can make us believe we’re hearing two different instruments. It’s just not in the nature of the beast.

Following the Italian Concerto, Schliessmann gives us what is perhaps Bach’s blockbuster non-organ keyboard work, and likely his most popular, the Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue. Believed to have been composed between 1717 and 1723, during the composer’s time in Köthen, it dates from the period during which Bach was experimenting with various systems of tempered tuning that led to the first book of his Well-Tempered Clavier in 1722. The Chromatic Fantasia and the WTC (I) were written around the same time and possibly even overlap. It’s now thought that the fugue was added to the Fantasia at a later date.

In the manner of its virtuosic, seemingly improvisatory style, the Fantasia part of the piece isn’t entirely unique. Bach was certainly familiar with the toccatas, ricercars, and fantasias of Frescobaldi and Froberger, many of which exemplified the so-called “fantastic style” (stylus phantasticus), popular as early as the end of the 16th century. What is likely unique, however, about Bach’s Fantasia is that it’s thoroughly chromatic, and not just successively but consecutively or serially. In other words, it doesn’t simply modulate freely from one key to another; it abuts diminished seventh chords by chromatic half-steps, one immediately after the other, thus sounding all 12 tones of the chromatic scale.

Some may be disappointed that the mathematically minded Bach didn’t come up with a 12-tone subject for the Fugue, but as noted earlier, the Fugue was most likely not composed at the same time as the Fantasia. There have even been suggestions that the Fugue might not be by Bach but by one of his contemporaries, and that it was only later tacked onto the Fantasia when it was finally published.

As can be guessed, the pair together require the utmost in virtuosity and control from the player. The Fantasia is extremely demanding for the duality of its requirements. On the one hand (no pun intended), it engages both hands simultaneously in equal oppositional playing, which requires enormous discipline and concentration; while on the other hand, the player must simultaneously display the virtuosic flair and sense of freedom that convey the impression of a toccata-like improvisational style. And that’s just the Fantasia. Add to it the rigorous technique demanded by the Fugue, and you have quite an exhibitionistic tour de force. Little wonder that the work was a favorite of Mendelssohn, Liszt, Brahms, and other 19th-century virtuoso pianists, and still attracts keyboard artists and thrills audiences to this day. In Schliessmann, the work has found a modern-day master and magician.

To conclude disc one, the pianist turns to Mendelssohn’s Variations sérieuses. Over 100 years and an entire historical era, the Classical period, may have intervened between Bach and Mendelssohn, but it was Mendelssohn more than any other composer that we have to thank for ensuring and enshrining Bach’s legacy in music history. Mendelssohn was a tireless advocate for Bach’s music and an assiduous student of Bach’s counterpoint and methods of composition. Yet I couldn’t help but wonder if there wasn’t some deeper connection between the works on the disc by Bach and Mendelssohn’s Variations sérieuses that led Schliessmann to include this particular Mendelssohn work.

The answer is a partial yes. That the Variations is in D Minor, the same key as the Chromatic Fantasy, is the least and most superficial of the similarities. More significantly, the theme on which the variations is based is highly chromatic. Within its first eight bars, each of the 12 tones of the chromatic scale is sounded at least once. It is no less difficult to write a set of variations on such a theme than it is to write a fugue on Bach’s chromatic subject. Both are equally unpromising, yet both motivated their respective composers to produce some very extraordinary music.

Did Mendelssohn feel challenged to see what he could do working in the variations form with a thoroughly chromatic theme? Who can say? What can be said is that Schliessmann brings an expressive beauty to the slower variations and a dramatic intensity to the faster variations that I’ve rarely heard in this piece. For an example of the former, listen to Variation 14, and for the latter, to Variation 9.

Disc two is considerably shorter, consisting mainly of Schumann’s Fantasie in C, op. 17, followed by Chopin’s Waltz in CT Minor, the second number in the composer’s set of Three Waltzes, op. 64. And finally, there come the two encore pieces listed in the headnote to this review.

Schumann’s Fantasie, as a composition, needs no introduction. It’s likely his greatest and most famous work for solo piano, not to mention one of his top contenders for most technically difficult. In fact, on a scale of 1 to 5, pianolibrary.orgrates the second movement of it the penultimate entry in its category 5 list, edged out only by the Presto finale of the composer’s Piano Sonata No. 2 in G Minor.

Such ratings, of course, are relative. What poses near insurmountable difficulties for one player, another player might find more tractable to his or her technique. If Schliessmann is challenged by the piece, you wouldn’t know it from listening to him play it. He has reached the pinnacle sought and coveted by all players, which is to surmount all technical obstacles to the point where conscious awareness of them ceases to exist and all that is left is to dwell in the higher realm of pure music-making.

Burkard Schliessmann is in that class of musicians. His latest album is most assuredly a must-have for pianists and lovers of solo piano music, but also, I’d say for the general music lover as an example of what musicianship at its finest is all about.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978