Fanfare

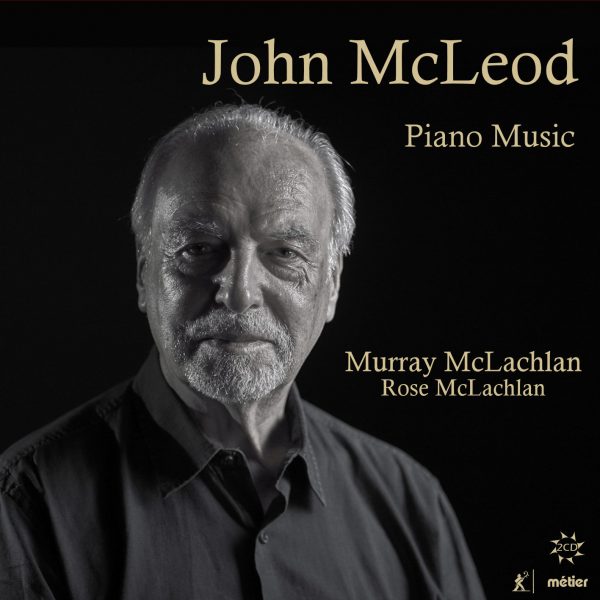

A setting of folk tunes, a clutch of impromptus, a collection of aphoristic miniatures preceded by whimsical Ogden-Nashian verses (Haflidi’s Pictures), some transcribed film music: This might, at first, appear to be a fairly lightweight collection. Whatever else you can say about the piano music of John McLeod (b. 1934), however, it’s anything but breezy. Taught by Lennox Berkeley and strongly influenced, especially after a year of intensive study of their music, by Messiaen, Birtwistle, Lutoslawski, and Boulez, he seems more interested in provoking than in diverting; and while his piano music is certainly not doctrinaire (as Boulez’s is), it’s largely characterized by a hard-hitting, knotty Modernist surface.

The music on this set is not without lyricism (try the wistful Impromptu No. 3 or the third of the Hebridean Dances), but it’s far more likely to be jagged; it’s not without intimacy, but it’s far more likely to be vehement; it’s not without moments of consonant beauty (say, the almost Elgarian passage as we move toward the end of the last of Haflidi’s Pictures), but it’s far more likely to be densely dissonant. Writing of an earlier recording of Haflidi’s Pictures, Colin Clarke said: “There is depth aplenty here, plus some playfulness” (Fanfare 33:3)—and it’s significant that the playfulness comes in a distant second. For the most part, this is deadly serious music.

Take, for instance, the last of McLeod’s Protest Pieces (actually, piano interludes from a song cycle, Chansons de la nuit et brouillard), entitled “The stag, its heart pierced by an arrow, disappears into the mist.” You might, from the title, expect a wispy, melancholic post-impressionist supplication; but while the work does end in uneasy quiet, the overall mood (as is appropriate for a work re¬sponding to “the universal themes of animal cruelty and environmental pollution”) is violent and angry. Even when Robert Carver’s medieval Missa I’homme Arme gets entwined into the Third Sonata, McLeod’s voice seems largely unaffected; there’s nothing here like the kind of union we get between Hildegard von Bingen and Christopher Theofanidis in Theofanidis’s Rainbow Body, composed just a few years later. To my ears, at least, what Margaret Murray McLeod (in her illuminating notes) calls the “Puck-like” elements in the Fifth Sonata are less “impish” than edgy.

I realize that there is a sweeter side to McLeod, for instance his Tombeau de Poulenc for flute and piano, and what I’ve heard of his orchestral music seems more expansive and less gnarly than the piano music (certainly, his Nielsen-inspired orchestral work Out of the Silence features bursts of attractive exuberance rarely heard here). But it seems (although it’s hard to be sure, since so little of his work is available on disc) that his piano music has drawn from his more rigorous and tenacious side. Most of the music on this set is highly concentrated, and demands tremendous concentration from its listeners.

It also demands tremendous concentration from the performer—and Murray McLachlan, who commissioned the Fifth Sonata and transcribed the Fantasy (originally for guitar and orchestra), and who has recorded much of this repertoire before, plays with virtuosity and commitment. This music has many of its roots in Liszt (in fact, the First Sonata is explicitly modeled on the B-Minor Sonata), and McLachlan goes at it with enthusiasm. In the past, I’ve felt that McLachlan’s playing lacked color and personality (a view shared by, among others, Raymond Tuttle; see his review of Stevenson piano music, 37:1), but that’s not as much a problem in this repertoire as it is, say, in Prokofiev— and in any case, you’re unlikely to hear much of this music in other hands. McLachlan’s young daughter (16 at the time of this recording) acquits herself nimbly in the Hebridean Dances, and McLeod is a wonderfully deadpan narrator in Haflidi’s Pictures. I do wish that the program booklet had included the pictures themselves, as the earlier recording did, and I wish the recording itself were a little less boxy. But those are minor complaints about an adventurous project.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978