Fanfare

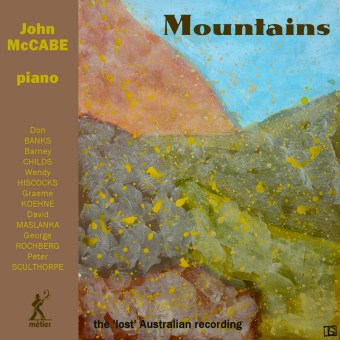

This disc has huge discographical and historical value. This is a “lost” recording by composer and (here) pianist John McCabe, that he made during a visit to Australia in 1985. The venue is actually EMI Studio 301, Sydney, and to this day we have no exact date apart from early June. While the recording has been transferred from Dolby cassette to compact disc for Dinmore Records, Paul Baily has worked his magic for this 2018 restoration and remastering. A final thread is Oscar Torres, who contributed final edits to the last movement of the Rochberg. Do not let the words “Dolby cassette” put you off: The sound is way more than just acceptable; the piano has body, and one can relish McCabe’s artistry.

There’s no better place to start, surely, for this antipodean adventure than with the magnificent music of Peter Sculthorpe. We need to hear more of this composer’s music; Sculthorpe speaks on a deep, almost ancestral level, akin perhaps to Birtwistle although with very much a language of his own. Commissioned for the Sydney International Piano Competition, Mountains is a response to the contours of Tasmania (Sculthorpe’s place of birth, incidentally). McCabe sculpts Sculthorpe’s harmonies perfectly; listen in particular to the weighting of the chords, which are everywhere perfectly judged. A rival performance by Ananda Sukarlan on Verso offers finer sound and an impressive performance, so it is context that may well swing it for the purchaser: The Sukarlan is part of an all-Sculthorpe chamber music disc that also includes Sculthorpe’s beautiful Night Pieces for piano. Looking purely at Mountains on its own, McCabe’s ear for chord placement and balancing is what has swung it for me, though.

The 1983 Toccata by Wendy Hiscocks (b. 1963) is precisely what it says on the tin. The work follows on naturally; Hiscocks was a pupil of Sculthorpe’s. The Toccata was only two years old when this recording was made, and McCabe brings to it a sense of vitality and excitement, with a perfectly judged toccata touch. For contrast, David Maslanka’s Piano Song (1978, written at the MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire) revels in slowly unfolding, beautiful sonorities which early on seem to imply Debussy’s “Cathédrale engloutie,” moving on to shimmering, tremolo textures. Its haunting nature leads to Don Banks’s Pezzo Dramatico (published in 1956). A pupil of Mátyás Seiber and Dallapiccola, Banks employs serialist techniques within an approachably expressive umbrella; McCabe finds the lyricism which is so much a part of Banks’s angular lines. Just as the Hiscocks found balance through the gentler Maslanka, so the Banks finds its complement in Graeme Koehne’s Twilight Rain (1979). If the title might seem to imply Takemitsu, it is Debussy’s shadow that falls most over this lovely, interior, enigmatic music.

Written for Jerome Lowenthal, George Rochberg’s Carnival Music (1970) is by some way the most extended piece here (25 minutes in duration). Rochberg himself has stated that the work explores contrasts of different musics; it does so with great effect. A mutation of Stravinsky’s Petrushka seems to inform the opening “Fanfares and March”; the march itself is decidedly more populist. Everyone, surely, on listening could guess the next movement’s title: “Blues.” Rochberg’s take, at least in McCabe’s hands, seems relentless. The emotional pain is visceral. McCabe, who provides the booklet notes for this piece, states that he thinks the central Lento doloroso is “distantly related to the Bachian arioso.” The relationship is indeed distant, but there. Another Bach reference hovers behind the scenes of the “Sfumato” movement, the F-Minor Sinfonia, this time alongside Brahms (op. 76/8). The movement title refers to a painting technique in which figures emerge from veiled backgrounds, and Rochberg invokes this idea impressively. Finally, there comes a “Toccata-Rag,” which binds in references to the march of the first movement and the “Blues” panel. McCabe’s recording acts as an excellent complement to Lowenthal’s own superb recording of the Rochberg, on Bridge (see review in Fanfare 37:6). While Lowenthal’s recording is far superior, I would not like to be without both. This is the first of McCabe’s recordings of the Rochberg; as he believed this performance would not be issued, he rerecorded it for Continuum records.

Finally, we have Barney Childs’s Heaven to clear when day did close (1980). Childs was both Professor of Music and Professor of English Literature at Redlands University, California; quite an achievement. His 1980 piece heard here has a co-dedication, one of the dedicatees being McCabe. The stillness implied in the title (from a Jonson poem) is achieved at the piece’s close, a haunting way to end a most stimulating disc. Those wishing to explore his music further should head over to New World Records for an all-Childs disc that includes a performance of this piece by David Ward Steinman.

This is a fabulous testament to the multiple talents of composer and pianist John McCabe (1939–2015).

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978