Infodad

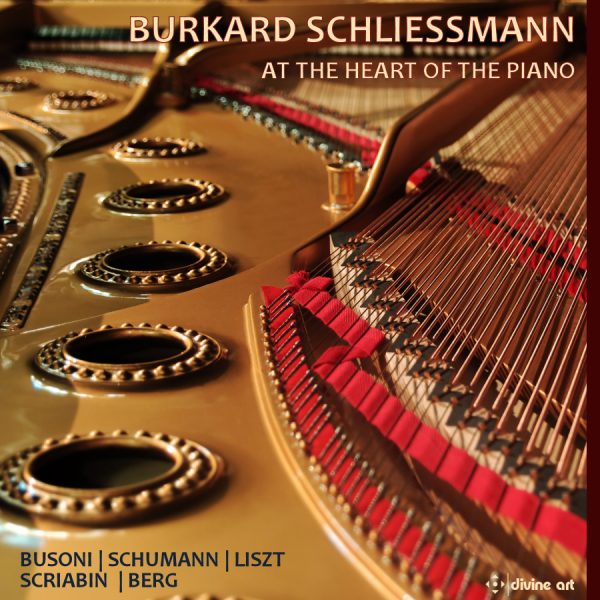

Fine performances of fine music stand the test of time on two levels: that of the music itself and that of the interpretations. Burkard Schliessmann proves a first-rate interpreter of a variety of Romantic piano music on a new three-CD release on the Divine Art label – and in so doing, affirms or reaffirms the quality of the works he plays. The performances are not new: all date to 1990, 1999 or 2000 and were released on CD before, except for those of Busoni’s Chaconne and Berg’s Piano Sonata, Op. 1, which are of the same vintage (1994) but have not previously been issued. The entire set of recordings has been remastered, but that is not an especially significant matter in recordings that were originally digital, although certainly everything here sounds fine – and has been remastered in such a way that any sound changes associated with the use of different Steinways are not apparent.

What does matter is the quality of Schliessmann’s playing and the service of the music at which he puts it. On that basis, this is a very fine release/re-release indeed. It is dominated by Schumann, for whose works Schliessmann clearly has particular affinity. The Symphonic Études, Op. 13 have elegance and sweep in addition to attention to the fine detail inherent in the carefully crafted variations. And the Fantasie in C, Op. 17 scales emotional heights with unerring skill, giving full expression to the “Florestan” and “Eusebius” elements of Schumann’s personality. Similar expressiveness, combined with truly impressive power to evoke the piano’s near-orchestral capabilities, is present in Liszt’s Piano Sonata in B minor, which inhabits an emotional landscape different from Schumann’s but which, to Schliessmann, is cut from similar cloth in terms of the relationship between technique and the evocation of feelings.

Schliessmann very effectively makes a similar argument regarding Scriabin, whose place on the cusp of Romanticism’s end is one thing that makes his music difficult to interpret successfully. Schliessmann deals with this by simply accepting Scriabin’s substantial debt to the Romantic era, whether or not he fits easily into it. Piano Sonata in F-sharp minor, Op. 23 has a distinctive mixing of Baroque underpinnings with virtuosic technique – a thoroughly Romantic combination. Two Études – Op. 2, No. 1 and Op. 8, No. 12 – are charming, almost pastoral. And Schliessmann gives plenty of evocative individuality to a considerable selection of Préludes, offering Op. 11, Nos. 1, 3, 9, 11, 13 and 14; Op. 16, Nos. 3 and 4; Op. 27, Nos. 1 and 2; Op. 37, Nos. 2 and 3; and Op. 51, Nos. 2 and 4. In truth, this rather scattershot mixture of material – with the Op. 11 works not even offered in the order in which they appear in the total set – is something of a disappointment, not because of the playing or interpretation but because there is a feeling of disorganization bordering on disorientation in the choice to present these specific pieces in this specific and rather arbitrary order. This becomes clear in the other Scriabin works here, the Deux Danses, Op. 73, and the entire Cinq Préludes, Op. 74. In both those instances, especially the latter, it is easy to hear each small piece’s independence and clear communication, while also picking up on the context in which Scriabin places it. This makes Schliessmann’s finely honed interpretations all the more impressive. His finely balanced and carefully considered handling of the remaining two works heard here are first-rate as well. These two pieces – one of which appears first on the first disc and the other of which is heard last on the third – are the least overtly Romantic pieces Schliessmann plays, yet both show their ties to that era quite clearly in these performances.

Busoni’s Chaconne in D minor, after Bach’s Partita No. 2, BWV 1004, uses Bach as a jumping-off point for a work whose sound differs as much as possible from that of Baroque times – but, in that reinterpretation of an earlier era, reflects the way in which many Romantic composers rethought Bach and altered his works for their own purposes (as in, for example, Brahms’ Symphony No. 4). And Berg’s Piano Sonata, Op. 1, which retains the tonal clothing of the Romantic era, at the same time contains hints that music itself is changing in as-yet-undefined ways to something derived from Romanticism but quite different from it. The skill with which Schliessmann makes this point, without ever being untrue to the music as Berg created it, is just one pleasure among many in this three-hour-plus offering of top-notch interpretations of multifaceted works.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978