Records International

This is a fascinating and stimulating recital disc that traces the evolution of 20th century avant garde piano music from pre-dodecaphonic Schönberg on the cusp of atonality to what the pianist describes as “without question the most substantial response to the third piano sonata of Boulez … recorded here for the first time” – Gilbert Amy’s Sonate.

Schönberg’s Drei Klavierstücke of 1909 introduce the disc with the composer attempting to break the bounds of chromatic Romanticism that he had stretched to the limit in the Second String Quartet with its excursion into the air of a different planet, and Verklärte Nacht. The pieces are widely regarded as atonal, though they abound in rich, only fleetingly functional, tonal harmony. Iman emphasizes this aspect of the pieces most convincingly, so they sound less like precursors to Boulez than companion pieces to Erwartung, with which they were contemporaneous. This is especially true of the caliginous Op.11 No.2, with its atmosphere of brooding menace and sudden, histrionic climax. There are still rival views of Busoni’s transcription of this piece from the set (Iman plays the original); one camp holds that his “Klavierfaktur” approach to the piano writing made it more pianistic and a more successful piece of piano music; the other, reinforced by statements in a letter from Schönberg to Busoni (despite their differences, the two composers maintained enormous mutual respect- and it should be remembered that it was Busoni who espoused “a new æsthetic of music”, while Schönberg proclaimed that there was still plenty of music to be written in C Major) suggests that such an approach was antithetical to what Schönberg had set out to achieve.

Paradoxically, though, especially when played with this kind of atmosphere and expressive potency, it is immediately apparent what drew Busoni to the work. Only in the fractured and recombinant third piece (which stands some way apart from the first two) does Schönberg approach his avowed intention of “complete liberation from all forms, from all symbols of cohesion and logic” (all symbols of logic? Really?) – and even here, the piece is highly structured through motivic cross-references, and dramaturgically contoured through strong contrasts in texture and harmony (yes, harmony, used “expressively” of course). The juxtaposition of the published sections of the Boulez 3rd Sonata with the Schönberg shows just how far the quest for total serialism transported the twentieth century avant garde away from its expressionist roots. The work as it stands is incomplete, according to Boulez’ original five-movement plan. In this sonata, the composer experimented with aleatoric composition, though, characteristically, in a highly controlled and structured way. Trope is in four parts, with relatively familiar degrees of freedom assigned to some aspects of the score that can be determined by the performer. Constellation-Miroir (even the title is a concession to its incompleteness, as the published section is the retrograde version of Constellation) is more complicated; the score is printed in sections, colour-coded and with arrows indicating the many permitted combinations. Given that the material in these sections is tightly organized, serially, the labyrinthine overall structure of the music is daunting to comprehend, which in essence is why Boulez’ many years of work never resulted in a version of the entire piece that was satisfactory to him. The sequence presented here is the result of Iman’s years of performing and continuous study of the work and its internal logic.

Webern’s characteristically spare and delicate Variations display his approach to tone rows as providing several structural, thematic, and narrative components within a piece, which is broadly the reason why he became the fons et origo of the total serialism movement later in the century. Iman’s comments on the work cannot be bettered: “The first movement is in ternary form wherein each phrase of the A section is an exact palindrome (the result of combining a row with its retrograde), each phrase of the B section ascends and descends the range of the piano, and the A’ section is a combination of both treatments. The second movement is in binary form wherein all of the gestures are equidistant from A 440. This treatment of symmetry gives the impression of certain events being affixed to a particular register. The third movement is the only one that is a set of variations. In this movement Webern exploits the fact that certain permutations of the row share several notes in common with other rows. This allows him to overlap the rows and adjoin each variation to the next such that the elision results in the beginning of the statement of the row being “misaligned” with the beginning of the variation. This gives the impression that the pitch content of each variation is changing.” Webern seems to have wanted a highly expressive treatment of this work, which is what it receives here.

Gilbert Amy had the good fortune to study the piano with Yvonne Loriod, who introduced him to Boulez. This was pivotal in the evolution of this work, and the composer’s subsequent embrace into Darmstadt. He had a distinguished career as conductor, composing all the while, and for decades now has been a much awarded and decorated national treasure in France. Amy’s Sonata is an early work, from the late 1950s and early 1960s; the octogenarian composer was still producing new scores well into the 21st century. It resulted from the intersection of his consulting Boulez about a piano piece which became the first movement of the sonata and the influence exerted on the younger composer by Boulez’ own 3rd Sonata. The material of the work is entirely serial; under the influence of Boulez, it was explored further in the subsequent two movements, in a complex mobile form. The level of complexity of this “garden of forking paths” is apparent from Iman’s description: “Mutations is printed on large sheets and in six colors, each color representing a “circuit” to be chosen and followed by the performer (only one such circuit is performed). These circuits are segmented into structures of various sizes which are arranged along a vertical and horizontal axis. The placement of a segment along the horizontal axis indicates its execution in linear time while the placement along the vertical axis indicates its tempo. While the execution of the segments must be in linear order, the performer is free to begin with any segment they wish so long as they complete the circuit. Occasionally different circuits cross and require the interjection or combination of material from other circuits. Sometimes the result is that the pitch material of two circuits is the same, at others this requires the performer to play the material of two separate circuits simultaneously. Lastly, many of the pitches are placed within a “time band” (similar to a measure, in the conventional sense) at the discretion of the performer such that the placement of the notes spatially within a “time band” does not indicate their order of execution. Interférences is printed in four colors on a score with complicated folding. Here the colors represent different structural groups—preparatory, developmental, concluding, and transitional—which are adjoined according to certain conditions.”

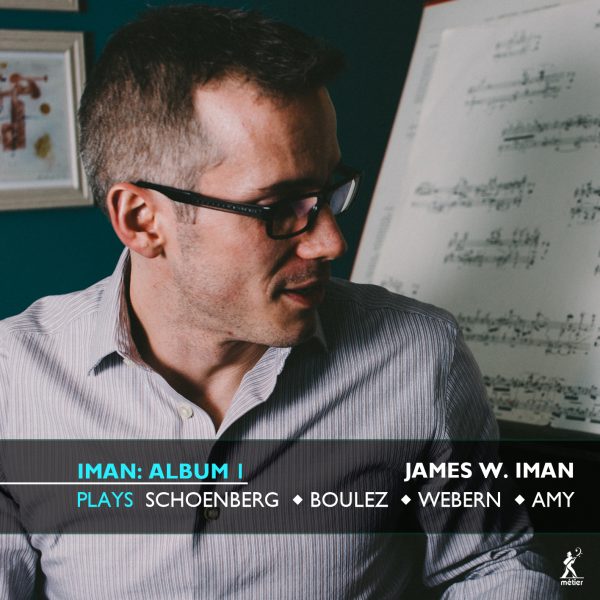

This is the first of three recordings by Iman to be released by Metier and is a remastered re-issue of a disc from short-lived Belgian label ZeD (The other two albums are new, recorded in the summer of 2022) and focuses on two composers of the Second Viennese School (Schoenberg and Webern); one from the Darmstadt School (Boulez) and French composer Gilbert Amy, a contemporary follower of the serialist movement, and greatly inspired by Webern though writing on a larger scale.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978