Fanfare

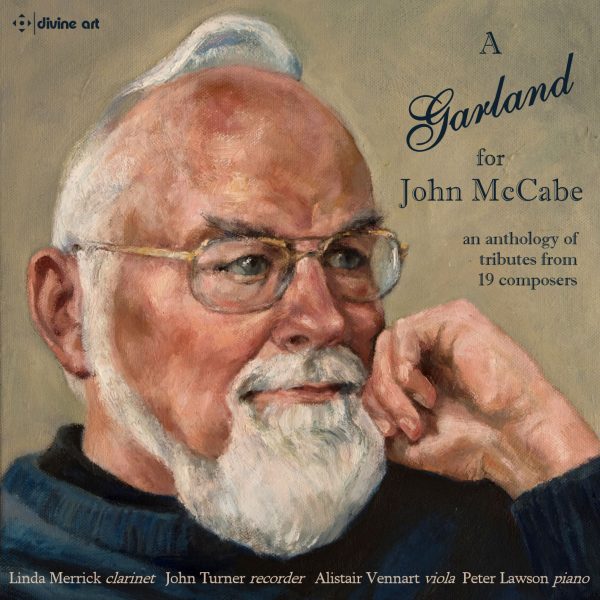

In many ways, this disc makes me very happy. I encountered John McCabe (1939-2015) a number of times, always at a distance and always in awe and admiration of who he was and what he stood for. A Mozart concerto performance with the Hallé was the first occasion (the Concerto No. 19, I seem to remember: He used music, but what a tender central movement). Performances of his wind music followed, and then concerts of his music in various locations around the UK. He was often present at these performances. The list of composers here shows in what high regard was held; a more eloquent in memoriam could hardly be imagined, and all credit to Divine Art for hosting this tribute from a total of 19 composers. The project was overseen by the recorder player on the disc, John Turner. McCabe’s wife, Monica McCabe, speaks eloquently of McCabe’s generosity towards his fellow composers; she also mentions his contributions to the musical world pianistically, not least in the field of Haydn sonatas and Nielsen piano music.

My own memories of my brief encounters with McCabe remember him as a happy, enthusiastic man. It is fitting, then, that the present disc should begin with the happy A Rag for John McCabe, which quotes from the introduction to McCabe’s own Lamentation Rag (a BBC commission for the 250th anniversary of Haydn). Scored with a deliciously light touch, the message is clear: Let us celebrate the man and his music, as well as his infectious enthusiasm. John Joubert’s Exequy is at the other end of the emotional scale, a lament for solo viola that quotes the Russian Kontakion, a chant for the dead; it also uses a musical cipher of McCabe’s name. A more touching performance than this, by Alistair Vennart, is difficult to imagine. While Joubert uses a number of compositional ploys for his excellent piece, Edward Gregson’s John’s Farewell for recorder and piano succeeds through its charming, heartfelt simplicity. It is a sarabande, stately and dignified.

The disc mixes up the combinations of the four instrumentalists involved, with occasional tuttis. One such tutti is Robert Saxton’s evocative A Little Prelude for John McCabe, another piece which plays with the letters of its dedicatee’s name (the last four, in this case, acting as a cantus firmus). One of the most aurally beautiful contributions, Saxton’s piece is all the more eloquent through its simplicity of compositional means, the overlapping descending fragments leading to a final, radiant, consonance. Skempton’s Highland Song exudes the nostalgic regret of music of that territory while, indeed, nodding to McCabe’s connection to Haydn (the latter composer’s Scottish Songs). Tender and febrile, Skempton’s piece settles for a low dynamic, restrained yet utterly heartfelt, and beautifully performed here with utter control by Turner, Merrick, and Vennart.

It is plainsong that underpins Elis Pehkonen’s Lament for the Turtle-Dove (Benedicamus Domino). A theme and variations that leads to a lament and inspired by a succession of birds (the final lament is for the turtle dove, but there is no missing the birdsong; even a non-ornithologist like myself can spot a cuckoo). The clarinet lament is beautifully done by Linda Merrick. As a possibly even more fascinating background construct, Robin Walker takes a late-1930s song I’ll Walk Beside You (recorded by English tenor Webster Booth), providing in his piece a question for the answer of the song title. Walker’s piece is delightful, but look a little deeper and there is a deft compositional hand at work.

Inevitably for McCabe, the name of Haydn has already cropped up a number of times in this review, as it does again in Malcolm Lipkin’s In Memoriam John McCabe (a transposed snippet from one of the piano sonatas); all the more surprisingly here, given the disjunct nature of the lines. Just as notable is the weight of sadness borne by some of the chordal structures Lipkin works with, heard bare on the piano; the lachrymose colorings of clarinet and viola garland the chords with grief.

The potentials of any 12-note row are huge, so it is a nice touch that William Marshall, in his Little Passacaglia for recorder and piano, uses a row from McCabe’s Bagatelles for Piano of 1964. Palindrome meets ground in a fascinating excursion; it is almost like being taken for a dodecaphonic walk. The piano provides a complex, spider’s web type of texture over which the recorder seems to cogitate in a parallel reality. Marshall’s work is dedicated to the performer here, John Turner.

A six-note cypher (HCCABE) is the basis for Martin Ellerby’s Nocturnes and Dawn (Patterdale) for viola and piano. Even the title here is a tribute (a translation of the title of McCabe’s Notturni ed Alba plus Patterdale in the Lake District of England, a favored place of McCabe’s). More Haydn (a well-disguised Symphony No. 47 finale) follows, but what I find really impressive here is the sense of peace, as if seen through a window in the rain. (Could that, perhaps, be a reference to the Lake District, too?) The sheer control of Alistair Vennart on the viola is remarkable. It’s lovely to see some music by Rob Keeley here. More cypher is at work in the Elegy for John McCabe for clarinet and piano; Keeley’s stated intention is to move from the austere to the lyrical, and he does so in patterned autumnal lights and shadings.

The combination of recorder, clarinet, and viola is a fascinating one. James Francis Brown’s Evening Changes invokes earlier eras effectively, while using evocations of pealing bells as a sound that has continued through the ages. The crepuscular writing is underlined by the warm timbres of clarinet and viola, lightened by the pipings of the recorder. This is one of the most fascinating pieces on this particular cornucopia. The first piece in the collection to touch on Minimalism, Gerard Schumann’s Memento for solo piano utilizes a simultaneous major/minor dissonance to shattering effect. The performance by Peter Lawson is beautifully unhurried, judged perfectly, the chords consistently intelligently placed and voiced.

Recorder, viola, and piano form the trio for Anthony Gilbert’s The Flame has Ceased. Reflective and sophisticated, Gilbert presents a lament that speaks powerfully through sparse textures: Less is decidedly more here. In contrast. Christopher Gunning’s Danse des Fourmis honors McCabe’s sense of humor deliciously, with recorder and clarinet engaged in a dance over the piano’s staccato background. This is a wonderful pairing of pieces. I have waxed lyrical about the music of David Matthews a number of times in the pages of this august publication: Particularly recommendable are the discs of his string quartets on Toccata Classics. Deliberately honing down the mode of writing, his Chaconne for Clarinet, Viola, and Piano makes its effect through its sparseness.

While I remember McCabe in Mozart, composer Raymond Warren remembers him in Ravel, and as part of his tribute he consciously adds a hint of French harmony to his In Nomine for recorder and piano, which he casts in the form of a French Baroque overture. Given the restricted dynamic range of the recorder, this inevitably becomes a rather internalized French overture. The restrained yet playful fast portion of the piece has something slightly sinister underlying it, its atmosphere strangely reminiscent of that of Britten’s opera The Turn of the Screw.

The title of Emily Howard’s Outback (for recorder, clarinet, viola, and piano) was suggested by the composer’s wife. It revisits Howard’s earlier work for piano Sky and Water, placing them within a portrait of a bleak, open landscape. Often on the threshold of audibility, the piece almost seems to depict a retreating.

More memories come flooding back with the name of Gary Carpenter, as I was present in my early, pre-university days at a composition competition at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester that he won. His piece Edradour, for all four instruments involved in the disc, sports a title which refers to the name of a single malt whisky beloved of McCabe. It is an active, bright, dancing piece whose occasional shadows only serve to emphasize the indomitable spirit of John McCabe, its dedicatee.

The disc is a wonderful tribute to a major compositional talent for whom full recognition is yet to come. Oftentimes, death can lead to exaggerated post-mortem claims; in John McCabe’s case, it has offered us an opportunity to see just what an influence he had as well as just how beloved he was. The next step is a fully fledged re-appraisal of McCabe’s own music, of course.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978