Infodad

There is a tendency among some people to think of older music, specifically Baroque music, as elegant, refined, and essentially impersonal, a set of exercises in form rather than emotional expressiveness. Listeners who have heard the works of Johann Jakob Froberger (1616-1667), however, know how far this is from the truth. Froberger, one the earliest developers of the dance suite and one of the most-skillful creators of this movement sequence, composed highly distinctive forms of movements that again and again had the same designation, including Allemande, Courante, Gigue, Sarabande and others. He also created program music – indeed, music whose programs were so precise that Froberger often wrote them out, sometimes in very considerable detail, on the same pages as the musical notation.

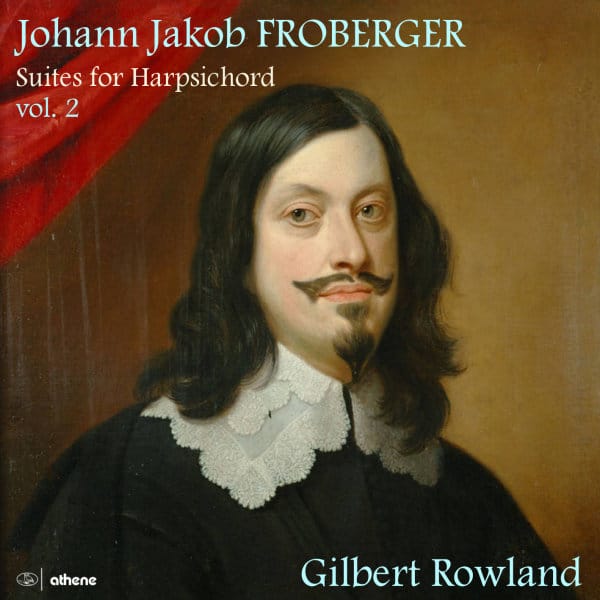

The second volume of Gilbert Rowland’s very well-played selections from Froberger’s suites, now available as a two-CD set on the Athene label, is an exceptional introduction to the composer or, for those who know his music already, a delightful expansion of their knowledge, since it is unlikely that many listeners will already be familiar with all 12 of these suites. The very first one offered here (in D, FbWV 620) opens with a descriptive and very personal movement bearing the title Méditation sur ma mort future, and although it is no more lugubrious than other movements in these suites, the mere existence of the title engages listeners in thinking about the topic that Froberger raised 400 years ago – and perhaps even about their own mortality. The rest of this four-movement suite consists of a Gigue, Courante and Sarabande, and all the other suites here – one in three movements, one in five, the remainder in four – are simply sequences of these and other dance movements. But “simply” is the wrong word, because Froberger’s rhythmic irregularities and unusual handling of Baroque dance forms give the music a level of complexity that Rowland explores with considerable skill and careful attention to period style and Froberger’s particular sense of it.

Froberger was quite prolific and quite protective of his music, allowing only two pieces to be published in his lifetime and having friends and noble patrons keep and control the rest. And he apparently really did have a sense of ma mort future, since he is known to have made funeral arrangements for himself the day before he died. He is an unusual and highly creative composer, and was known as a keyboard virtuoso – as is clear from the demands of the suites that Rowland plays. Bach understandably thought highly of Froberger’s music, and the similarities and divergences between the two composers’ keyboard works are quite interesting. But hearing Froberger entirely on his own is all that is necessary to admire the quality of his compositions and the extent to which their content belies the notion of Baroque music as emotionally uninvolving.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978