Fanfare

Here’s the text with the line breaks removed:

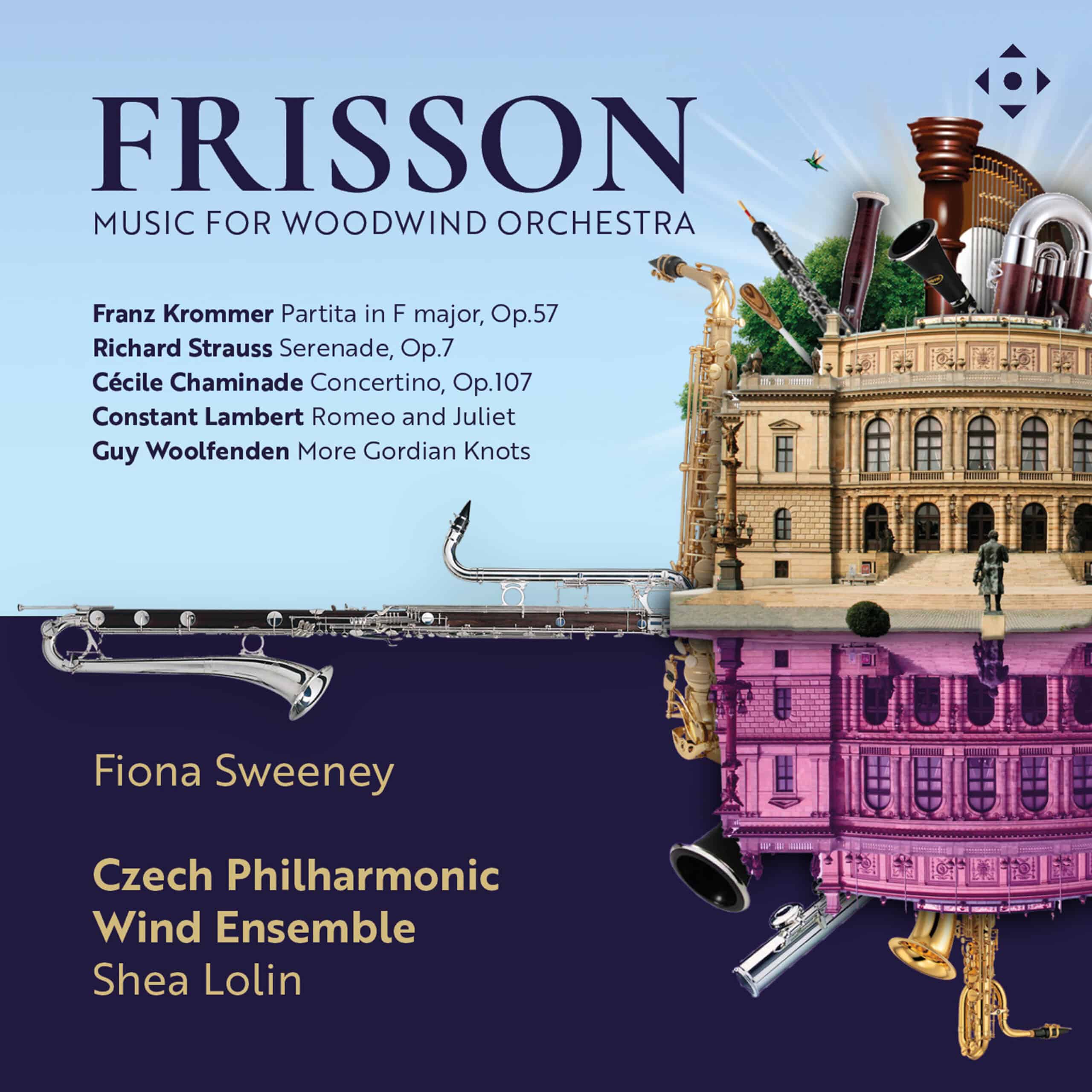

This is a lovely idea: music for winds that should be better known, performed by wind orchestra. This is obviously a labor of love from Shea Lolin, whose previous releases include Twisted Skyscape (Fanfare 47:4) and Chromosphere (not reviewed).

If ever there was a composer whose music fits the concept of Harmoniemusik like a glove, it was Fanz Krommer (1759–1836). His works are as much a joy to play as they are to listen to, and heard in Shea Lolin’s arrangement, contrasts are heightened without altering the underlying ethos of the music. Listen to the beginning of the development section of the first movement of Krommer’s op. 57 Octet-Partita. More than eight players here, but the spirit remains. It is interesting to compare this recording with the original scoring via the Netherlands Wind Ensemble’s Philips recording, which is a classic, sprightly and free. Inevitably, one hears the shifts to the minor more in the Czech performance, and gestures become more marked (even gothic!). Heft does not mean lack of velocity: the Menuetto under Lolin dances along beautifully (it is marked Presto, after all). The Andante cantabile makes quite a mark via the Czech players: that characteristic richness and deep bass of the Czech Philharmonic itself pays great dividends here. And what fine oboe playing from Jana Brožková. There is the most remarkable moment when Krommer just concentrates on a sonority, too: he is not just background fluff to outdoorsy events, but a really talented composer. The leaner sound of the Netherlands ensemble remains powerful, though. I confess to having bad memories of the final movement: there is a high horn solo that requires an eighth-note top C, almost like a “pop,” on an off-beat, and fair to say it never went well. I seem to remember I once tried to sing the high C (sounding F) through the instrument instead of playing it; that went even less well. Lolin circumvents the problem by putting the relevant phrase on saxophone, on which there is considerably less sense of contained panic. Busy arpeggiations in this “Alla polacca” go swimmingly via the Czech players. All great fun.

And it is simply lovely programming to have Richard Strauss’s op. 7 Serenade of 1881 here in a few new colors. The piece is a tremendous outpouring from the heart that should be played much more often. The recording has more interesting moments of sax color, but it maintains the warmth of this early work. Again, the Netherlands ensemble released a classic recording of the original (Fanfare 14:4) and it is worth comparing the scorings. Saxophones might not sound particularly Straussian, but Lolin’s take is nothing if not interesting, and the playing is unfailingly beautiful. Again, the warm Czech sound is perfect. Admittedly the climax around six or seven minutes in does sound rather bloated, and the passage after nine minutes is rather heavy. But do give this a try.

You might well be concerned about the Gallic delicacy of Cécile Chaminade’s Concertino for flute and orchestra with wind band. Worry not. This is a brilliant reimagining, in which massed winds exude a sense of Frenchified elation when called for. Flutist Fiona Sweeney excels, although one might find the close placement in the sound image a step too far (it is a bit intrusive). Sweeney appeals more than Susan Milan (Fanfare 14:2) and even Sharon Bezaly (but Bezaly is better recorded: Fanfare 37:3); Sweeney’s cadenza is little mystery tour all of its own, and the elision back to background woodwind glow is one of the highlights of the album.

Constant Lambert’s Romeo and Juliet was one of only two English ballets performed by Diaghilev’s company. There is quite the story behind it: apparently because of a disagreement between Lambert and Diaghilev, the latter put the parts under police guard lest Lambert tamper with them. If you want to hear all the ballet, Norman del Mar with the English Chamber Orchestra on Lyrita is the place to go, recorded in July 1977 at Kingsway Hall, London, all charm (and complete). Arthur Lintgen loved it as well, in Fanfare 31:5, while in more modern times there is always John Lanchbery with the State Orchestra of Victoria on Chandos (similar high praise from Paul A. Snook in Fanfare 24:5). I have a soft spot for Lyrita recordings, though, so that is the one I return to. Here we have selections: “Romeo and Juliet Meet at the Ball” retains the bright breeziness of the music (I defy you not to smile) while hammering home the deliberately destabilizing dissonances. The Neoclassical aspect seems emphasized here, perhaps because winds and Neoclassicism have their precedent in Stravinsky. The siciliana that follows, “The Professor Teaches a Pas de deux,” has a cheeky little limp to it, while some of the sonorities seem to link to Pulcinella. Some sterling bassoon work here, too. There is a kind of controlled chaos to the opening of “The Lovers Are Separated,” while imitation is used to suggest the chase. There is a “Death of Juliet,” featuring dissonances of a sort of exquisite pain, again quite Stravinskian. Finally, the eminently chirpy “The Curtain Falls” is as chipper as they come, and performed with the peckiest staccato here. The arrangement is deft, and true to the composer’s vernacular. It should be noted that the movements featured here are the ones the composer himself suggested may be extracted.

To my surprise, Guy Wolfenden (1937–2016) makes his debut as a composer in the Archive here, with the late (2010) piece More Gordian Knots. Wolfenden was no stranger to writing for concert band, and indeed this is the one piece on the disc not in arrangement by Lolin. There are three movements, “Air,” “Chaconne,” and “Jig.” These are Gordian knots as, in 1995, Wolfenden had been inspired by Purcell’s theater music while searching the English master’s songs for Thomas Southerne’s play The Wives’ Excuse. And so Gordian Knots for clarinet choir was born. It is no surprise that there is this trajectory, given Wolfenden’s time as Head of Music at the Royal Shakespeare Company for full 37 years. Inspiration came from Purcell’s music for The Gordian Knot Unty’d of 1691, with the finale, “Jig,” using the tune Lillibulero as a ground bass (a technique beloved of Purcell, of course). More Gordian Knots is not a “second suite”: it is an arrangement by the composer of the original for wind orchestra. The present conductor gave the premiere of the arrangement, in 2010, with the Bloomsbury Woodwind Ensemble. Wolfenden’s writing and scoring are impeccable, as is this Czech performance. There is real lyricism to the “Air,” too, and one cannot but help notice a kinship between Wolfenden and Lambert. The “Chaconne” sounds far more objective, and far more veiled (some lovely clarinet solos here), and with the ground bass come hints of harmonies from Purcell’s time. A contrabassoon, clearly, underscores the final cadence before that concluding “Jig” brings sunshine.

A beautifully programmed, supremely well executed disc, finely recorded in Prague by producer Mikel Toms and engineer Vítek Kral. Recommended.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

We noticed you're visiting from France. We've updated our prices to Euro for your shopping convenience. Use Pound sterling instead. Dismiss

![🎧 Listen now to the @purcellsingers' first single from their upcoming album, #ASpotlessRose! ➡️ listn.fm/aspotlessrose [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/642752592_1424641949105789_8815810652567824072_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=106&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=iGIrDXgtiUoQ7kNvwHBL_3c&_nc_oc=AdleXtjXE7YN0ZtsLfCquKnUGbak1hw27hmgkuQBKnCA6-4RE0iLehmY7wdaZMyweTo&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=QVIw9c9zY552CVGL9DtX3A&_nc_tpa=Q5bMBQFZT9jz8vroAoq5G5pPFO1BQ-XZn_RkBerM-0w55D9KHV3ehktxiLTSplo38lNAv8YC2LaGjCE4xQ&oh=00_AfyzQ2Dp8wdTqHk_tIJJtDMyOG5kYFM0xIdfCrNkm0vaDw&oe=69B4C341)