Fanfare

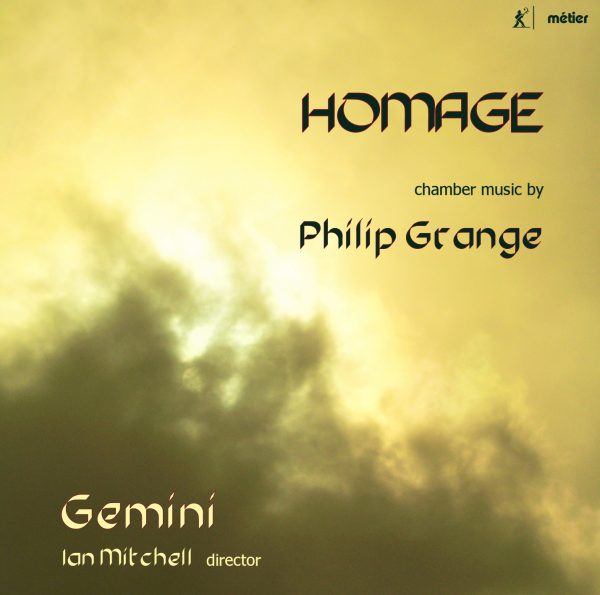

The well-established British composer Philip Grange (b.1956) realized in a moment of reflection that his music frequently took off from other creative artists and writers. From that reflection comes this new release titled Homage, which comprises four chamber works that pay homage to a painter (Marc Chagall), two writers (Samuel Beckett and Edward Thomas), and a fellow composer (John Casken). These pieces call for different personnel pulled from the chamber ensemble Gemini: a piano quartet, piano trio, solo cello, and a sextet of mixed instruments including percussion and piano. Grange supplies helpful commentary about how each homage came about, and there’s a note from the conductor of Gemini, Ian Mitchell.

I mention these peripheral aspects of Grange’s music because in some ways they are the most interesting things about it. There is a serious attempt to “absorb” another artist’s technique, as Grange puts it. More than four decades ago he read Samuel Beckett’s novel Malone Dies, which uses stream of consciousness as the dying protagonist entertains himself with invented stories. How can stream of consciousness be translated into music? Grange posed the question, and Shifting Thresholds, the sextet, is his answer. Chagall had a repertoire of signature images, such as angels and farm animals, that were repeated from canvas to canvas, acquiring different perspective and colors. Finding a musical equivalent led to Piano Trio: Homage to Chagall.

By going into such enticing detail, Grange has found a hook, not just for his own imaginative process but also for the listener. If you know Chagall or Beckett, you sit back and await the trans¬mutation of one art form into another. I wish I could say that insight came. As a listening experience, Grange’s fairly generalized Postmodernism delivers no obvious resemblance to the figures he pays homage to. The piano quartet, Tiers of Time, is supposedly related to the strata of rock seen in the hills of England’s bleak Peak District, but all musical forms beyond a simple one-note-at-a-time are layered. Over the course of 70 minutes the only association I could make was in the solo cello work, Elegy, whose mournful tone is easily connected to the death in World War I of the gifted poet Edward Thomas. Even here, however, the wandering line of the music ventures far away from anything one thinks of as elegiac.

Grange, like many other contemporary composers, is embedded in the far-reaching academic system that provides music for specialized performers like Gemini. It typifies the coterie culture, being extremely skillful and eager for new compositions (Gemini has commissioned three works from Grange over a period of almost 30 years, including the Beckett homage, which lasts half an hour). The wider music-listening public is occupied elsewhere and has ears attuned to composers of the past. There are times when the coterie and the public converge. Peter Maxwell Davies, the teacher and close friend of Grange’s, attained fame, popularity, and respect inside the composer community.

To my ears Grange’s music stays firmly inside the academic-coterie boundary, but that doesn’t make it any less accomplished. I had a mixed response to the program. The Elegy for solo cello be¬comes tedious after a few minutes, which is a risk that unaccompanied cello music runs, but the Piano Trio is full of interesting techniques and sounds. It benefits from the narrative quality that is central to Grange’s style—in other words, the piece seems to head somewhere and does appealing things along the way. There is also a pull toward tonality rather than complete atonal liberation, which also helps the listener.

The big work, Shifting Thresholds (the title comes from a Beckett poem), has a much more colorful palette than the other three works, since the sextet includes a variety of flute, clarinets, violin, viola, piano, and percussion. But the music abandons any narrative—like Beckett’s prose, Grange says, the piece has no goal—and there is more reliance on atonality, including quarter tones. The real question, which applies to all contemporary music, is whether it appeals to your ear. I liked the Piano Trio and piano quartet more than anything else. Overall, Grange’s compositions are ingeniously nondescript. It’s not a flattering assessment, but when a composer can employ any stylistic tool, nothing personal emerges. You are unmoved by the listening experience despite all the enticing descriptions provided in the booklet.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

We noticed you're visiting from Latvia. We've updated our prices to Euro for your shopping convenience. Use Pound sterling instead. Dismiss