Fanfare

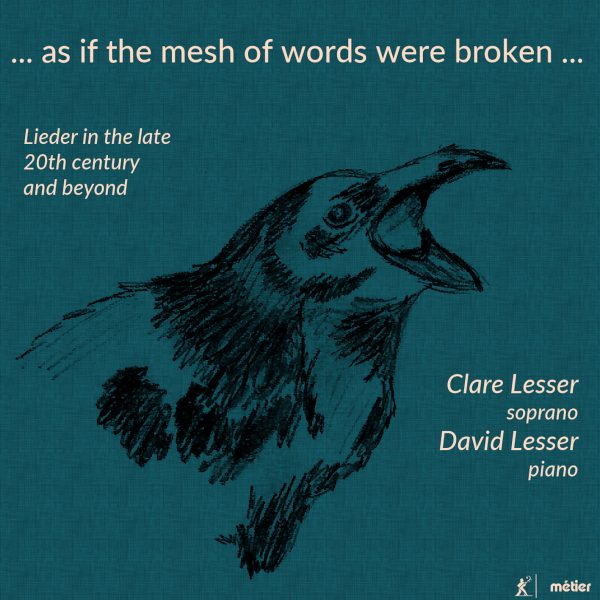

By presenting Lieder from the late 20th and early 21st century, Metier Records presents vibrant proof that the art form of the Lied is alive and well. Heinz Holliger’s “four bagatelles,” his Dörfiche Motive (Village Motifs) sets poetry by Alexander Gwerder with Webernian concision. Both the second and third songs are based on a single chord each. If both Boulez and Schoenberg can be discerned from Holliger’s musical surface, the overall effect is of subjecting those voices to a prism, distilling their essence within an umbrella that is all Holliger. How expressive are the extended intervals of the third song, “Die Hand im Gras,” against a foreboding, strangely isolated piano backdrop.

Three sets of Holliger songs are punctuated by works by Rihm, Finnissy, and David Lesser. Of the three, it is Rihm whose voice we hear first, in his Hölderlin-Gedichte. Immediately the musical space feels more lyrical, Clare Lesser seeming to whisper, melodically if not necessarily tunefully, into our ears. The cycle is a study in decay, a study in unraveling and disintegrating an art-form, as Rihm subverts expectations regarding function (the codas in particular). Clare Lesser finds just the right blanched sound; the central, and longest song, “Halfte des Lebens,” is massively unsettling, an effect directly related to the technical control of both soprano and pianist.

The second group of Holliger settings is to poetry by Mileva Demenga (Fünf Mileva-Lieder, Mileva is the daughter of cellist Thomas Demenga, a friend and collaborator of Holliger’s). There is a Bergian fragrance to “Der Abend kommt,” the language couched in that of Romantic Lieder with a hint of folksong. As the cycle progresses, so does the complexity of Holliger’s writing, culminating in a set of mirror canons in the final “Möge sich dein Leben….” The darkening of the harmonic world is palpable from the opening cry of the fourth song, “Königsblau ist der Himmel,” before the rather Schoenbergian lines of that final song curl around each other.

It’s good to see more than one Michael Finnissy representation in a single issue of Fanfare-, elsewhere, I report on a Metier disc of some of his music for string quartet. The melodic lines of his songs here are angular, but also intensely lyrical: The bitter-sweet harmonies in the piano for “Hier ist mein Garten bestellt” (the first line of the first poem, the first four words of which form the title of this song dyad) underpin Clare Lesser’s astonishingly pure, beautiful delivery. Amazingly, her diction is excellent, but most impressive is the sheer accuracy of her slurs over large intervals. The texts are from Goethe’s Romische Elegien, texts suffused with the force of Nature. The restraint of Finnissy’s setting makes the texts all the more powerful.

David Lesser’s own Dritte Trakl-Musik is part of a larger cycle that is ongoing. A study in speeds of emotions traveling from the outside world into the inner, the piece could hardly ask for a finer interpreter than Clare Lesser (who is, to all intents and purposes, a latter-day Cathy Berberian). The German texts, in electronically altered form, are counterpointed against Clare Lesser’s foreground; Gerhard Gall is the native German speaker (he is also a German language coach who has worked with the likes of Glyndebourne Festival Opera, the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, and Bayreuth).

Finally, there comes Holliger’s set of six songs on poems by Christian Morgenstern. This is very much a work in progress: When the present performers rehearsed with him in 2016, Holliger made changes during that process, and there is also an orchestral version. The set is absolutely beautiful, from the French-influenced warmth of “Der Abend” (Fauré weighs heavily here) to influences elsewhere of the likes of Busoni and Neoclassicism. The earliest Holliger work here (1956-57), the premiere of the orchestration was given in 2004 by Juliane Banse, with the composer conducting the Lausanne Chamber Orchestra. Perhaps there is a parallel here in Berg’s Sieben frühe Lieder, in which a composer revisits earlier works; along with that there is a parallel to Boulez, for whom pieces were rarely “finished” and remained in a state of flux, awaiting polishing or revisiting. The piano original remains highly evocative and effective, especially with a pianist of David Lesser’s caliber.

The whole disc operates as confirmation that the Lied remains in fine fettle; the combination of Clare Lesser’s pinpoint accuracy and understanding, plus David Lesser’s fine pianism and a splendid, truthful recording, is a powerful combination.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

![🎧 Listen now to the @purcellsingers' first single from their upcoming album, #ASpotlessRose! ➡️ listn.fm/aspotlessrose [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw6-1.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/642752592_1424641949105789_8815810652567824072_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=106&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=cc73JkyCr_0Q7kNvwECnfn2&_nc_oc=AdlqbggKJngslvYrn_NHqW2Ag98CHx_FIegKiNNQeMKw96qwCNRRBE-EEtJv-dsB9-w&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw6-1.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=kqnwW4edH-o_2ziMOosrcQ&_nc_tpa=Q5bMBQEaAzH-UggCDiuhXbrFT1HIQGdEPxawLqTh8T2XOYl0kJtuXroRJwSvSTdRMk3bBGG7RCSPQlUtgA&oh=00_Afw5y1jKk0LgbIdEk2Gg0y0qTQyw54VAT-h1ohi9-DQZAg&oe=69B998C1)