Fanfare

The UK-based Kreutzer Quartet has been closely associated with the fascinating, multi-layered music of Michael Finnissy for some time now, and has premiered a significant number of his works. Only three of Finnissy’s works actually have the title “string quartet” (two of them written for the Kreutzers: see Robert Kirzinger’s review of the first in Fanfare 22:5).

This is a most fascinating, and beautifully recorded, disc. The venue was St. Michael’s Church Highgate, London, its acoustic buoying the quartet sound while Jonathan Haskell’s recording skills keep the reverb exactly right, so that textures can shine and lines resound with utmost clarity.

The six-movement Civilisation (2004/2013) is a meditation on what civilization actually means, and if, indeed, it is actually civilized. Contrasting primitivo (performed sul ponticello) and calmo markings designate the two planes of the opening movement, the second the more obviously ‘‘civilized.” The technique of sul ponticello is transformed in the fragile violin duet that opens the second movement (so beautifully controlled here by Peter Sheppard Skærved and Mihailo Trandafilovski); this movement also quotes, or rather “examines,” the “Heiliger Dankgesang” move¬ment of Beethoven’s op. 132 Quartet.

Finnissy’s writing in the third movement is miraculous: a duet for viola and cello within a violin “halo” (a four-part chorale), which is itself mirrored by another viola/cello duet in the more lyrical fifth. Perhaps the epitome of civilization, the finale encapsulates the jaunty spirit of Haydn within Finnissy’s language. By utilizing the violin material from the “primitive” sections and recontexualizing it, Finnissy implies a sort of interiorization. Again, there is a half-reference, here to Haydn’s “Lark” Quartet, op. 64/5 (a piece which also influenced the music of Finnissy’s Second and Third Quartets).

The “continuation” of Bach’s “Contrapunctus XIX” from Die Kunst der Fuge (2013: Finnisssy apparently dislikes the word “Completion”) is a real achievement. Bach’s counterpoint builds while also bending; in response to Finnissy’s wishes, perhaps, it is listed as one of his own works, as op¬posed to an arrangement or completion of Bach. The purity of Bach’s writing, so memorably given by the Kreutzer Quartet, seems almost to seek to distort itself as the piece progresses, as if via a fair¬ground mirror. This performance was recorded in one take, to reflect the single arc of the piece. There is also, incidentally, a version for piano trio.

In contrast to the strictures of the Bach/Finnissy (if I may break with convention and call it such), the Clarinetten Liederkreis (2016) opens out into a more overtly serenade-like manner. Cast in five movements, it begins in the most delicate of fashions, as Linda Merrick’s beautiful sound meshes with and colors the strings. The texture gradually grows in complexity in the opening movement: The Schumann referent becomes blindingly clear in the warmth of the harmonies that open the work’s second panel, while Finnissy’s cruelly high long notes for clarinet in this movement act to unsettle that harmonic glow. Calling for solo clarinet in the third movement implies a leave-taking, a statement of independence. The solo lines question, circle, ruminate. Marked Folklorico: quasi parlando, this is explicitly soloist as story-teller. The booklet notes suggest that this and the succeeding movement (for tutti) invoke Kodály (Galanta), Stravinsky (Soldier’s Tale), and Bartok (Contrasts), and it is certainly true there is a primal sense of the dance to this penultimate tutti vigoroso. The finale brings all instruments together with the same material in a crescendo to a climax, but with each player acting independently towards that climax. Independence remains to the end. This is a remarkable, fascinating piece.

The short Mad Men in the Sand (2013) is a scherzo, a skewed Mendelssohn with elements of Ives while referencing Alkan and invoking both a mad woman singing on the sand and a piece of 1970s erotica, Boys in the Sand. Skittishly performed, it acts as a perfect interlude.

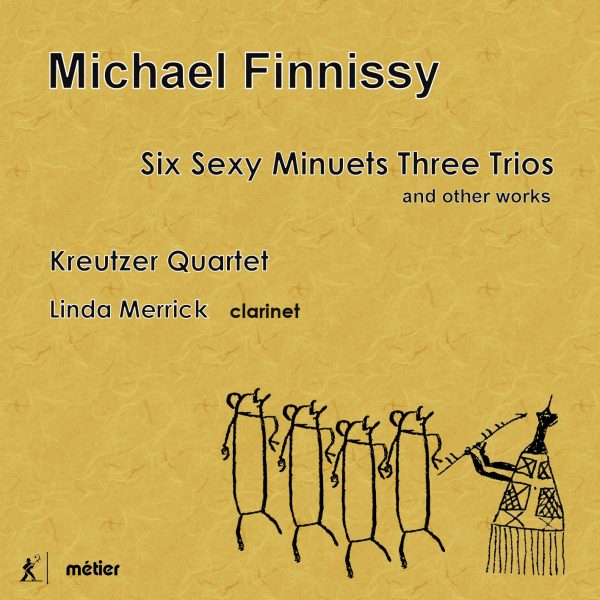

While the title of Six Sexy Minuets Three Trios (2003) might imply a continuation of scale and, indeed, erotica, this is in fact a 25-minute piece. The quartet also have at their disposal a number of household objects, such as china teacups (how English!), a leather-covered notebook, chopsticks, metal espresso cups, and a miniature score of Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro. We hear some of these objects solo in a remarkable “percussion” break in the work’s third panel. In each Trio, one member of the quartet is silent, making them literal trios as well as formal ones. Finnissy virtuosically pits Mozart and Haydn against Cage at one point (the Cage in question being the 1950 Quartet) while members of the Kreutzer Quartet reveal a virtuosity with spoons and other cutlery “like naughty children, at a Lyons Comer House” (violinist Peter Sheppard Skærved’s words) in the fourth movement. While the majority of the work comprises short movements, it culminates on an Andante malinconico of late-Beethovenian intensity, stunningly sustained by the Kreutzer Quartet.

The disc takes its title from the piece Six Sexy Minuets Three Trios, which acknowledges the lighter side present here. But there is so much more besides. This is at times a highly intense, but always rewarding, experience.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978