British Music Society

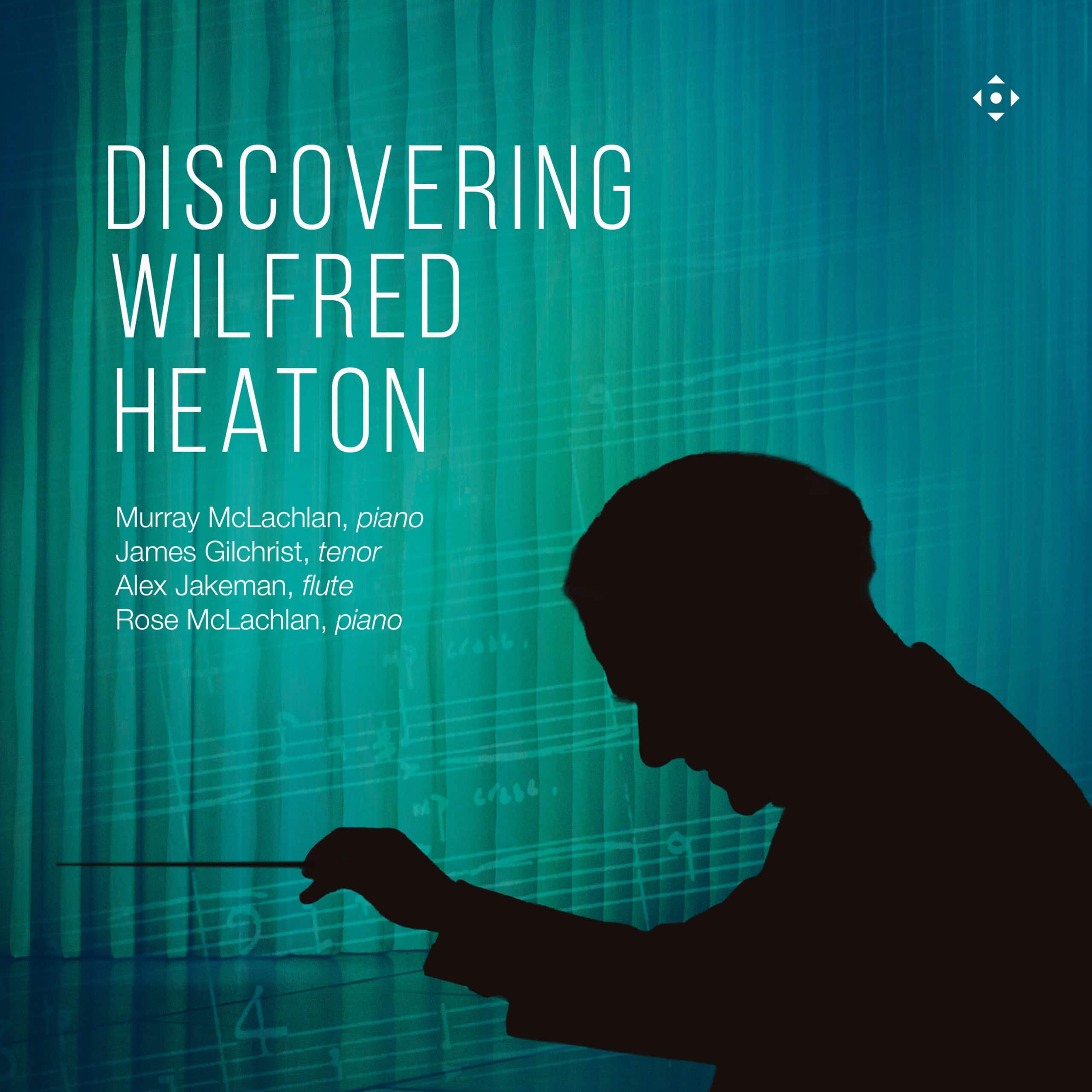

In my 2025 review of Paul Hindmarsh’s admirable and authoritative book on Heaton (1918–2000), I mentioned the imminent CD of his chamber music. Here it is. A welcome and most intriguing release, it covers Heaton’s composing life, from songs written as a teenager, to the mature visionary.

A quiet, devout, and conscientious individual, it must be recalled that the Salvation Army formed the parameters of his life for many years; and when he later adopted wholeheartedly the anthroposophical movement of Rudolf Steiner, his compositional life was heavily stifled. We must therefore thank the benign influence of Mátyás Seiber for nurturing the considerable gifts of his unconventional pupil, as well as Hindmarsh’s advocacy in editing and preparing these works, in what is a wide-ranging introduction to a largely unknown legacy.

The two Morning Songs, unabashedly romantic in the drawing-room manner of Somervell, are useful additions to the repertoire. With empty hands and Welcome for me must have startled the Salvation Army – I found the first unacceptably cloying, and the second disconcertingly meandering – but the two Love Songs from theatrical productions are more persuasive, although might perhaps struggle in the concert hall. They could all hardly be better sung than they are here.

Pilgrim’s Reflections also originates from the theatre: a production of Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress. The score consists of various cues which have been assembled skilfully by Hindmarsh into a most attractive concert suite (one of three), comprising nine variations on the folksong Valiant – now known as the hymn tune Monks Gate – sung to Bunyan’s words,‘He who would valiant be’.

It is an extraordinarily unexpected plunge from Heaton’s early conservative essays into the dense and virtuosic figurations of the monumental Piano Sonata, which is worth the price of the CD alone. The work is derived from material written in the 1950s, by which time Prokofiev, Bartók, and Walton were occupying Heaton’s thoughts and processes Although only the third movement (the mesmeric Lento) was completed in its entirety, a draft and an almost-complete fair copy have allowed Hindmarsh to assemble a definitive performing edition, from which Murray McLachlan gives a blistering account.

The Three Pieces, Heaton’s last work for the piano, continue in exploratory vein: a murmuring two-part invention, a Stravinskyian Andante that almost quotes Petrushka, an incisive Vivo. In a welcome change of colour, the Little Suite for flute and piano is a cheerful neo-classical rethinking of baroque dance suites, presented in a closely-argued but less astringent language.

Finally, we have three arrangements for piano duet of Evangelical tunes, of which the third seems to be a poor relation of The Quartermaster’s Stores. Heaton enjoys himself with limited melodic material, although none of these brief effervescences approach Arthur Benjamin’s less frenetic interpretations of Jamaican sources.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

![🎧 Listen now to the @purcellsingers' first single from their upcoming album, #ASpotlessRose! ➡️ listn.fm/aspotlessrose [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/642752592_1424641949105789_8815810652567824072_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=106&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=1oI-Pe3rGJ4Q7kNvwGwD6rQ&_nc_oc=AdnOGlvK5Us_VLBnLwAXVbIQaUdPockPUywtRBStWHWXWe8dd-w6DvieWb7mlLw-mow&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=VHMaR_6eLYuipd7fFY8YNg&_nc_tpa=Q5bMBQH2KupgiASh7qLHW9o9iwooC_rpE_JWSvAYRupB-l7yOMI5PXivVMCmZOqWz63eV2n6Ku4Kq9L9xw&oh=00_Afvl1KD-HuS99eSN1Fiw18hPpWHviq0Ge3FZcLuEwZNklA&oe=69A98E81)