Fanfare

I have long been intrigued by the music of Eugene Ysaÿe (1858-1931), the celebrated Belgian violinist and composer. That someone who could have simply produced bonbons (as did other violinists of his era who dabbled in composing) managed to become a musical creator of substance, and that without any formal compositional training, I find remarkable. Ysaÿe’s Six Sonatas for Solo Violin have been rightly celebrated and much performed, but the rest of his sizable output (most of it employing the violin) is less well known. Everything I’ve heard convinces me that Ysaÿe is a composer of stature, not merely a “violinist’s composer,” and worthy to sit beside the other important French and Belgian writers of his time. The music is forward-looking, resonant, eclectic, and sits at an interesting crosscurrent between late Romantic, Impressionist, and early modem influences. Ysaÿe was much respected as an interpretive artist and as a human being, and his compositions leave us a legacy of his artistic personality we would not otherwise have.

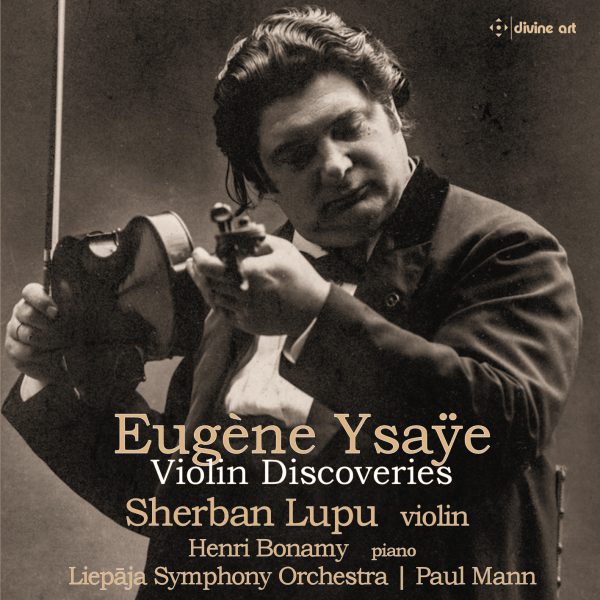

Ysaÿe was modest and reticent about publishing his pieces, and much of what he wrote still hasn’t seen the light of day. The present release is momentous in that it presents several Ysaÿe works never before heard, most importantly a violin concerto which he labored over and revised over nearly two decades. Ysaÿe is known to have composed at least half a dozen violin concertos, all unpublished, which have only gradually been brought to light. Romanian violinist Sherban Lupu has been working to unearth Ysaÿe’s manuscripts for several years now. The notes to this disc recount how he traveled to the library of the Royal Conservatory of Liege and found a pile of Ysaÿe manuscripts “sitting on the floor and covered in one inch of dust.” He proceeded to piece together the pages of the concerto, which as he discovered exists in four different versions written from 1893 to 1910. Lupu found a piano part for the concerto, but only fragments of orchestration, so Romanian composer Sabin Pautza orchestrated the piece in its entirety.

The concerto is a dark and brooding one-movement fantasia (Ysaÿe originally titled it Poème concertant) and one of the most extraordinary violin concertos I have heard. Some of the writing is of a surprising modernity for 1910, let alone 1893. Interestingly, we hear some pre-echoes of the solo sonatas. After a long, churning orchestral introduction, the violin enters with an unaccompanied monologue (the annotator says this is a unique occurrence in violin concertos of the 18th to the 20th century). With its twisting chromatic chant over a G-string drone, listeners may be reminded of the “Musette” variation in the Second Solo Sonata, although the effect here is much darker. Ysaÿe’s plan for the rest of the work roughly follows a broad sonata form, but his treatment is free and rhapsodic, and there is much passionate and compelling dialogue between the violin and the orchestra. The annotator hears the violin part as “desperately attempting through a prayer to reach God for answers” and the orchestra as intervening like a Greek chorus. Stylistically this concerto places Ysaÿe among the “advanced” composers of his day, and it is clear we are quite a long way from the world of Vieuxtemps and Saint-Saëns. The violin part bristles with difficulties both technical and expressive.

The rest of the selections on the disc, for violin and piano, also come from unpublished manuscripts uncovered by Lupu. They range in date from 1885 (Scènes sentimentales) to 1924 (Trois Etudes-Poèmes). The most notable among these morceaux are the short and eloquent Elégie and the third of the Trois Etudes-Poèmes, entitled “Cara memoria,” which is long and equally eloquent (and recalls the mood of the well-known Poème Elegiaque). The Elégie came without a title or an ending, so Lupu supplied both. The haunting melancholy of this piece makes it among the finer morceaux of Ysaÿe I have heard.

The violinist’s performance is somewhat variable. He plays always with temperament and panache, but the chamber pieces suffer from some uningratiating tone and intonation, which are aggravated by rather reverberant recorded sound. The concerto is far better recorded, and the violinist’s wiry tone gives the work an appropriately gothic character in places. The Liepaja Symphony Orchestra from Latvia is a fine ensemble and manages to make the thick orchestration perfectly clear and transparent, so that the genius of Ysaÿe’s writing shines through. Sabin Pautza has done a highly attractive and ear-catching job of orchestration, even including what sound like xylophone and chimes. For the music alone, this is an important release which all fans of the Franco-Belgian violin school should hear. The concerto in particular is a startling discovery which will be of interest to violinists everywhere.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978