Music Voice (Italy)

[This notice has been translated from Italian using Google (…) and then slightly edited to improve intelligibility. Any offer to re-translate would be welcomed!]

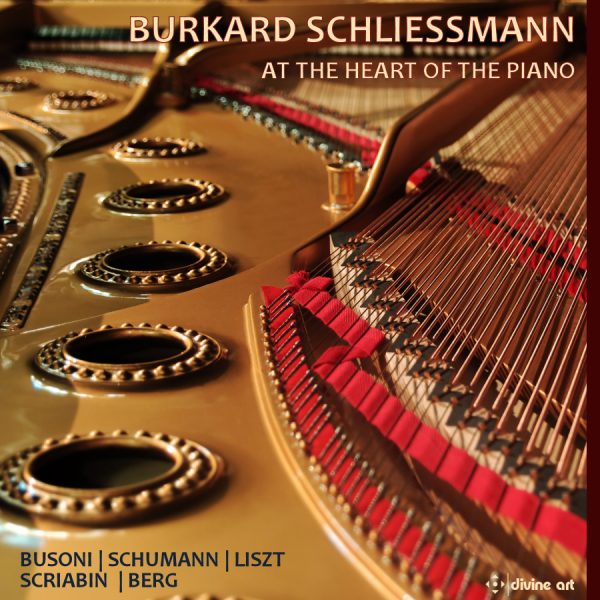

Burkard Schliessmann is one of the currently most appreciated and interesting German pianists at an international level and already boasts a large discography, mainly focused on composers who belong to the European Romantic school. Even his latest recording, a box set comprising three CDs published by Divine Art, does not differ from this principle, as the title itself, “At the Heart of the Piano”, demonstrates, The set presents Bach’s Chaconne in D minor in the transcription by Busoni, the Symphonic Studies Op. 12 and the Fantasia in C major Op. 17 by Schumann, the inevitable Sonata in B minor by Liszt; we have from Scriabin the Sonata in F sharp minor Op. 23, two Studies from Op. 8 and Op. 12, Preludes from Op. 11, Op. 16 and Op. 37 and the Two Dances of Op. 73 and the Five Preludes of Op. 74, ending with the Sonata Op. 1 of Berg.

Considering this program more carefully, on the basis of Schliessmann’s aesthetic vision, one can easily realize how the works and composers can be seen as an explanatory map of musical Romanticism, based not so much on a philosophy to be proposed through the overall sound, but more by rigorous formal study in which the key content of Romantic thought can be expresed without entering into contrast with what is exposed by the form itself. In this sense, Bach’s famous Chaconne, revised and enunciated by Ferruccio Busoni, is already symptomatic; the choice that Schliessmann makes is not in exalting the transcendental dimension with which this piece is usually presented, but by involving more the immanent aspect, that is the sensitive perception of the artist who performs it. The Chaconne, therefore, seen not in the Bachian vision mediated by Busoni’s technicality, but through the (late) Romanticism of the composer and pianist from Empoli, detaching himself from the pure spiritual dimension that inevitably invests Bach’s music, shapes the primeval matter according to the modalities and the urgencies of one’s time. From here, the technique itself becomes a form of transcendentality with which to draw the prerogatives of a vision, the Romantic one or at least of what remains of it, which observes, reflects and offers itself to the ear, heart and brain of those who listens.

But pay attention to an aspect that distinguishes the path of the program chosen by the German pianist, namely that there is a red thread that links each work in the recording to the next, not taking into account the chronological discrepancies of the program itself. Therefore, the Busoni who mediates and “actualizes” Bach is very close to that technical transcendentality evoked by both Schumann and Liszt, that is, by two custodians of the “sacred” Romantic vision. That is why, in the name of this “transcendentality”, Schliessmann continues his exploration of the Romantic genre, first with Schumann’s Symphonic Studies and Fantasia and then with the Liszt Sonata. And how does he deal with these pages? The Symphonic Studies undergo dilations and restrictions in the metronome, but this must not cause scandal, as the German artist bridges the possible time lags by frescoing the theme and the variations of this composition with a due passion, such as to give life to a sort of “story” (the “imaginative” Schumann that makes the art of sounds cross over into narrative and literary structures) that unfolds with a coloristic sagacity given to each of the twelve Studies, a color that Schliessmann exalts above all by emphasising the play of tonality given by the chromatic keys and the technique to be used on the basis of the same indications provided by Schumann, which leads to giving life to a timbral fresco that for some may even be exaggerated in its final result (there is effectism, pathos, emotional impetus; but, by God, are we or are we not in the heart of piano Romanticism?) This all however fully falls within the vision that Schliessmann wanted to impose here, which shows how this pianist does not at all suffer from a lack of personality, on the contrary. Hence, abundant monumentalism (Track X – Variation IX), but also soft, rounded brushstrokes, made crystalline (Track XI – Variation X and Track XII – Variation XI), that is, in the very heart of Op. 13, to better highlight the bipolar antagonism of the Schumannian personality, with Florestano and Eusebio going into the ring to give them a blessing.

Such monumentality and delicacy are consistently maintained also in the Fantasia Op. 17, which, as we know, is above all (see the first movement) a passionate and heartfelt act of love towards Clara Wieck and which Schliessmann explores with powerful, full, open, solemn sounds, giving an “architectural” identity to his pianism, in order to solidify the image of the “phantastisch”, as per Schumann’s indications. But also in this case the projection is valid, the “throwing-forward” with which the German artist permeates the entire program in question, that is, preparing the listener for the irruption of the Lisztian Sonata (chronologically, the Fantasia dates back to 1836, while the Sonata in B minor is from 1852 and is dedicated to Schumann). Schliessmann, therefore, ideally builds a bridge, a connection between the passion that seeks to be form, given by the Fantasia op. 13, with a form, precisely, that throws his cloak to the winds to rise to the most free, free from the impositions given by the classicism of the genre; he does it to remember once again how in just sixteen years, those that separate the two works, two worlds that while reconciled in their creative intentionality, are at the same time like two galaxies destined to expand and move away in space.

Here, too, the German pianist does not deny the characteristics of his program, since the reading of the Lisztian Sonata is devoted to yet another “look-ahead”, prefiguring, anticipating, acting as a precursor to what will come after and what Schliessmann justifiably identifies in Scriabin. But let’s go in order. The vision that the German pianist brings to the surface of Liszt’s Sonata is not only devoted to monumentality of form (an element inherited from the past, especially Schumann), but is based on a sound that is increasingly circumscribed in it, that is, enhancing the single sound as a self-referential datum, as a completely autonomous cell that compares itself with the other cells that precede it and with those that follow it. A sound, therefore, decidedly devoted to a modernity that if on the one hand will be deepened by Brahmsian pianism (the one that will fascinate Schönberg), on the other hand it will be faced by Scriabin’s visionary nature. Scriabin, whose pianism, together with that of Debussy, explores up to essence of the cellular element given by the harmonic conception which is transformed acoustically into a dimension in its own right and which at the same time manages to interpenetrate the other timbral dimensions that surround it and of which it is necessarily part.

And here we come to the third and last disc of this set and which I personally consider the most intriguing and stimulating. Schliessmann has included Sonata no. 3 Op. 23, the Etudes no. 1 Op. 2 and no. 12 Op. 8, the Preludes nos. 1, 3, 9, 10, 13, 14 Op. 11, nos. 3 & 4 Op. 16, nos. 1 & 2 Op. 27, nos. 2 & 3 Op. 37 and nos. 2 & 4 Op. 51; the Two dances Op. 73 and, finally, the Five Preludes Op. 74. If, in the words of Francis Bacon, the Schumannian Fantasia is given by the pars construens provided by Clara Wieck, the Sonata by Scriabin is modeled on the pars destruens of Vera Isakovic, the unfortunate consort of the Russian composer, who realized ever since his nuptial trip to Paris in 1897 of having made a tragic mistake in marrying her. Thus, if the Fantasia is musically a unifying part, the Sonata on the contrary is devoted to a disintegrating dimension. This disintegration is already an attempt to flesh out the sound, to make it closed in itself through a process of timbral legitimisation in which the phrasing already tends to fragment, to “sectorize”, as well as being, although in its emotional arrogance, more and more diaphanous, rarefied, almost suspended over the abyss of nothingness.

In his interpretation, Schliessmann instead tends to recover a formal legitimacy that allows one to still manifest a sort of “hope”, so that the phrasing is more fluid, less “bumpy”. This does not mean that a rethinking of the vision of “looking forward” is taking place in his interpretation, but it represents a reconsidering in perspective what will come in Scriabin’s musical poetics. Thus, the German pianist takes the Sonata no. 3 so that he draws a line of demarcation between what is still Romanticism and its passing phase, which in the Russian composer cannot be accurately defined as Late Romanticism per se. The disintegration, in this sense, materializes in the exposition and in its development and at last, in the “Presto con fuoco” which is the tenuous explosion of a continuity that is linked to what was stated at the beginning of the Sonata. And it is here that Schliessmann’s “reconsideration” transforms the “Presto con fuoco” into a launch pad through which to launch a missile whose expressive consistency is represented by the other works by the Russian composer included in this set.

And this has happened since the two included Etudes, in which the sound matter already manifests a change in progress in anticipation of what is destined to take place if it does not come true, that is, that Scriabin would have reached the archipelago of atonality by following a path different from that of Schönberg and the others belonging to the Second Vienna School. This happens from the Étude in C sharp minor which belongs to the Three Pieces of Op. 2 (dating back to 1886-89) and the last of the twelve Études op. 8 which are from 1894-95. These are two Studies that for Schliessmann evidently belong to that process of planning that lays the foundations for starting that specific alternative path to modernity, a modernity, mind you, which does not, however, deny what happened previously.

And here the Preludes taken into consideration, those belonging to Op. 11, Op. 16, Op. 27, Op. 37 and Pp. 51, appear to be nothing short of idiomatic in the choice of the German artist and represent a miracle of “oscillation”, a pendulum that passes alternately between what is still past (Op. 11 no. 9 – Op. 16 no. 3 – Op . 27 no. 2 – Op. 37 no. 3) and what is already future (Op. 11 no. 3 – Op. 27 no. 1 – Op. 51 nos. 2 & 4). Faced with such a choice that intends to show the Scriabinian two-faced Janus, it can and must appear completely obvious that the great final step is represented for the German pianist by the two last piano compositions of the Russian composer, namely the Deux Danses Op. 73 and the Cinq Préludes Op. 74, both dating to 1914, that is to say a year before his death. These two works are, as we know, intimately connected and represent, as Schliessmann points out with his reading of him, the ultimate offshoots of that romantic tension conceived within his aesthetic tradition.

Of course, especially the Op. 74 necessarily refers to the contemporary Six Pieces Op. 19 by Schönberg, an emblem of that process of harmonic dissolution that will inevitably lead to the concretization of seriality, but neither Op. 73 or Op. 74 boast the same purposes, as Scriabin, beyond the mystical intentions to which these last two piano works were designed, are extensions of a past that certainly looks ahead, but is not yet the future, as is perhaps the Schönberg Op. 19. This is why the interpretation made by the German pianist follows this “prudential” line, never pushed into formal excesses, and this is especially true for the Cinq Préludes, since their enunciation aims at least to be “nostalgic”, that is to say, of a past, in his tradition, which senses the moment of change, of passing away, of an end that can no longer be postponed (in this sense, the timbre dimension that Schliessmann provides in the second Prelude Op. 74 is exquisitely evocative).

Nostalgia has been stated. So, to conclude his program dedicated to Romantic transmutation in the piano, a transmutation with an alchemical flavor at times, Schliessmann puts his hand to Berg’s Sonata, which, just to underline the aesthetic purposes of the recording in question, is not addressed in its “radicality ”, but as a sign of something that has by now been lost, a footprint of an ancient stone that wants to be a milestone, that is, to act as a watershed between the (late) Romantic vision and the post-Romantic one. Following this path, I find that Schliessmann, at a piano level, does not differ from what Karl Böhm did at the directorial level by addressing Berg’s ‘Wozzeck’, therefore not considering it as an expressionist creature, a suspended bridge towards ‘Lulu’, but as the ultimate expression of a late Romanticism that was struggling to exhale the last breath.

From here, those who are familiar with the readings made, among others, by Glenn Gould of this Sonata, get ready for a performance by the German pianist in which the few motivic cells that animate it are never exaggerated, or brought to a point of tension close to rupture, but his reading is conceived as a repudiation of fragmentation, a look forward with a look backwards, also because Op. 1 itself is basically an act of gratitude towards that tradition (the Sonata dates back to the two-year period 1907-08, only to be revised by the author in 1920) which at that time is beginning to fall apart (and in this we follow the coeval path taken in parallel by Scriabin himself in that first decade on a sonatic level). Schliessmann thus uses the palette of a passion which, however, now smacks of consummation, a supreme act, a corollary that ideally closes the circle of his journey towards the funeral of Romanticism, returning an unsuspected evocative sweetness, a very fine shroud with which to wrap the corpse, so as to be able to preserve it from the corrosion of time and memory. So be it.

The recordings were made at three different times by as many engineers (ranging from 1990 to 2021), but we do not notice timbral and dynamic imbalances in the use of the piano, rigorously always a Steinway Piano D. Therefore, the dynamics always turns out to be strong, but at the same time sensitive and careful in restoring the necessary nuances of microdynamics; the sound stage adequately reconstructs the instrument at a discrete spatial depth, restoring a pleasant height in the sound, as well as filling the space between the speakers. Even the tonal balance and detail do not fail, with the first always precise in making the low and medium-high register always distinct and never blurred, and with the second showing a remarkable materiality in the physical rendering of the piano.

Artistic interpretation 4/5

Technical value 4/5

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978