Fanfare

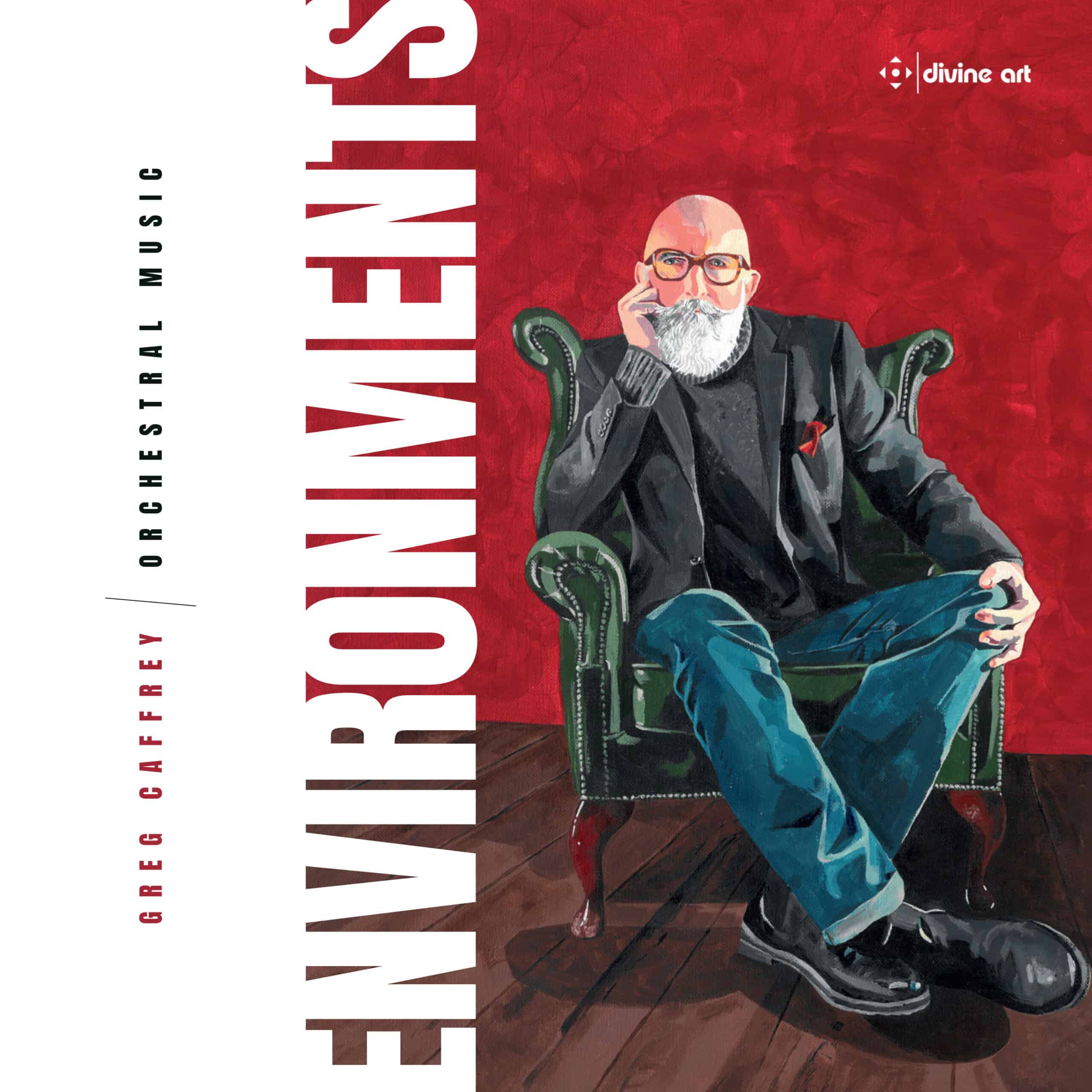

Just past 60, the Northern Irish composer Greg Caffrey is old enough to have been shaped by The Troubles in his native Belfast. The intensity of the strife made music education in his school impossible, but he went on to obtain degrees through the Ph.D. at Queen’s University Belfast. In his composer’s note Caffrey sketches in his memories of a terrible time but doesn’t claim that any of these four orchestral pieces refers to it. The closest we come is in the first piece, the nine-minute Aingeal II, where the angel of the title was “a person close to me. This beautiful person endured such pain and tragedy in her short life.”

Scored for string orchestra and percussion, the music’s poignant effect of “beauty, pain, and suffering” would be suitable for a piece about The Troubles, not as a depiction of violence, which is absent in the music, but as a human response in the aftermath. Caffrey’s chosen mode isn’t anywhere near the cutting edge of New Music, since he writes notated scores for acoustic instruments. His harmonic language roams around the same terrain as Bernard Hermann’s scores for Hitchcock movies, principally in Caffrey’s fondness for haunting atmosphere. It seems reasonable to take a sidelong glance at Peter Maxwell Davies, Oliver Knussen, and Magnus Lindberg for similarities in Caffrey’s use of the orchestra and his ability to put sophisticated gestures into accessible expression.

The two title works, Environments I and II, which together occupy about half an hour, communicate very little in their modest, neutral title, but Caffrey considers them among his most intuitive pieces. They were composed in Paris during residencies in 2011 and 2012. In keeping with the two solo instruments that are prominently used, Environments I is on a symphonic scale suitable for the piano, while Environments II is reduced to a chamber string orchestra in keeping with the quiet solo guitar. Despite some varying differences, both display Caffrey’s preferred orchestral sound, which amounts to a signature (as with Herrmann).

His sound revolves around dramatic gestures interrupting a sustained mood, with flecks of color from percussion, woodwinds, and brass. Forward motion and development are often less important than diving into the soundscape each piece is based on. In Environments I the piano is prominent, but much of the time it is the leading voice in the texture, not a conventional concerto soloist.

By ear I can’t follow the technical feature that Caffrey says he is exploring without actually describing it. But his sound is riveting in a way that displays a considerable ability to directly communicate with the listener. The effect is like lively stasis, if I can put it that way. Environments II works on the same principles and uses strings asimaginatively for color as the full orchestra in Environments I. The guitar is forwardly placed (without microphones it would be hard to hear in the concert hall), and as usual in guitar works with orchestra, solo passages are provided to make it more audible. Percussion aside, this is a piece for bowed and plucked strings that has a certain abstract angularity, which makes it more austere than the other works on the program. The piece that comes closest to being programmatic is A Terrible Beauty, the title taken from W. B. Yeats’s poem Easter, 1916. That week historically marked an armed insurrection against British rule by Irish republicans, the same conflicting forces as in The Troubles half a century later. Each of the work’s three movements takes a line from Yeats to suggest Caffrey’s response to a poem. But the essence of the score is similar to Aingeal II, in that what is terrible attempts to exist beside what is beautiful. It’s a rich subject for classical music going back centuries (the St. Matthew Passion could have been subtitled “A Terrible Beauty”).

Caffrey took eight years to compose the individual movements as free-standing pieces, which originally existed in chamber form to be premiered by an ensemble he founded and headed for a decade. Momentum and drive feature more prominently than elsewhere, giving a sense of dissonant propulsion only occasionally accented by a longer lyrical passage sounded in the upper strings. Although A Terrible Beauty lasts only 20 minutes, I didn’t find that there was enough invention or variety to sustain interest, but I imagine Caffrey sees this piece as his most advanced and exploratory. It is certainly the hardest listen on a program noted for its immediacy.

The performances by the Ulster Orchestra under conductor Sinead Hayes seem to be expert, committed, and well prepared, even if such things are hard to judge in unfamiliar contemporary music. The piano and guitar soloists in the two Environments aren’t given virtuoso parts, but Daniel Brownell and Craig Ogden perform with real presence.

Caffrey emphasizes that this was a major project of great personal significance for himself. The outcome is a happy one, and much of the music holds definite appeal for general listeners who are attuned to the poignant border between beauty and pain.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

![🎧 Listen now to the @purcellsingers' first single from their upcoming album, #ASpotlessRose! ➡️ listn.fm/aspotlessrose [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/642752592_1424641949105789_8815810652567824072_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=106&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=49FisD1EbHcQ7kNvwHB_sxM&_nc_oc=AdnfzKWpLe14XcaPihYb-sRtrYUxv4oSyDu4_2ZhCmI3Pk9EDAVp6MbgoDcgCAv1gUQ&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=SAF5RqsKOFX-KSujk_ttQA&_nc_tpa=Q5bMBQFJSLJKR4CA3tWtbiwMaeCXpB58x9dZdFw-rsyr2lafgorTHoY72ynUxAHPfC6_3OIxCC8d0bnJrQ&oh=00_Afyvdyh6kOLXTt7EwGf5rhN51-axUUhlPn-PMTRRdLmHXg&oe=69B614C1)