MusicWeb International

The title of the album derives from a traditional African text: “Why do birds sing? Because they have songs…” That seems as good a reason as any for God’s creatures, be they human or avian.

The inspiration for Edward Cowie’s Because They Have Songs came from an “Untamed Botswana Safari” he took in 2014. He writes that this was no normal tourist package but a 3000-kilometre journey. It touched on many Southern African landmarks, including the Victoria Falls, the margins of the Kalahari Desert, the Okavango Delta, and the Chobe National Park. The composer and his wife Heather saw a vast range of wildlife, including wild zebra and antelope. And then there were the birds…

Regarding Cowie’s method of composition, there is an interesting, innovative process at play. He said that as a child, before he could write crotchets and quavers, he was able to physically “draw sounds from nature”. Typically, he uses four notebooks in the field, one of which deals with the shape or form of his natural surroundings. The second majors on perceived colours, and those that blend or clash. Most creative is the third jotter, which records “representational” drawings of the birds, bees and flora. The final notebook features traditional musical notation of what he hears about him – be it birds, insects or water features.

Cowie suggests that these are “in the form of a translation or relocation of those natural sound-sources [made] into a potentially musical outcome”. His studies result in music that is “in almost all cases [a] quotation of an actual birdsong… [adhering] to the actual pitch and shape of that song”. This is often heard in the solo instrument, in this case a suite of saxophones, whilst the piano frequently provides the background atmosphere.

I asked the composer if there was any improvisation in this score. He replied: “[…] everything is notated but of course I always try to compose music where the performers can ‘bend’ and sculpt sound and rhythm in ways close to their own emotional place in the music”. This factor can conspire to make Cowie’s work feel as though it is being created on the spot – fluid, instinctive and liberated.

I wondered about an effective listening strategy for this concept album. I suspect that for many listeners, 88 minutes of sax and piano is pushing the attention span. Is it possible to listen to a Book at a time? Or even select a sequence of “birdsong” taken from all four volumes? There is no indication what the environment each book is evoking. Is it veldt, forest or desert? Or all mixed up? Without deep ornithological study, the listener will not be aware of each bird’s habitat. However, none of this really matters.

Cowie told me that Because They Have Songs can be “listened to in parts […] even just an individual movement […] these are not themes and variations, but instead clusters of very individual musical impressions, treatments, and responses”. Furthermore, it is not essential to understand the geographical, ornithological or topographical allusions or backgrounds to appreciate this imaginative work. That said, I did look up on Google maps Botswana and some of the geographical sites Cowie and his wife visited. And I could not resist looking at pictures of the evocatively named Southern Pied Babbler, Helmeted Guinea Fowl and the Scarlet-Chested Sunbird.

I make no attempt to explore each of the twenty-four feathered friends featured here, and neither does the booklet. One impression I gained was the subtle influence of jazz. This was reinforced by the scoring for the saxophones. I thought of innovative performances such those by the late Miles Davis. Cowie told me that in his younger days he was impressed by the sounds of the Modern Jazz Quartet and Dave Brubeck. (He was not a Mod in his younger days, was he?). Beyond this, there is little to pin down the stylistic effect of this work. Messiaen perhaps, but there is no suggestion that Cowie has religiously adopted the Frenchman’s modus operandi. Absent from these pages is any theological speculation, beyond a numinous wonder at the marvellous natural environment, whether created by a Deity or not.

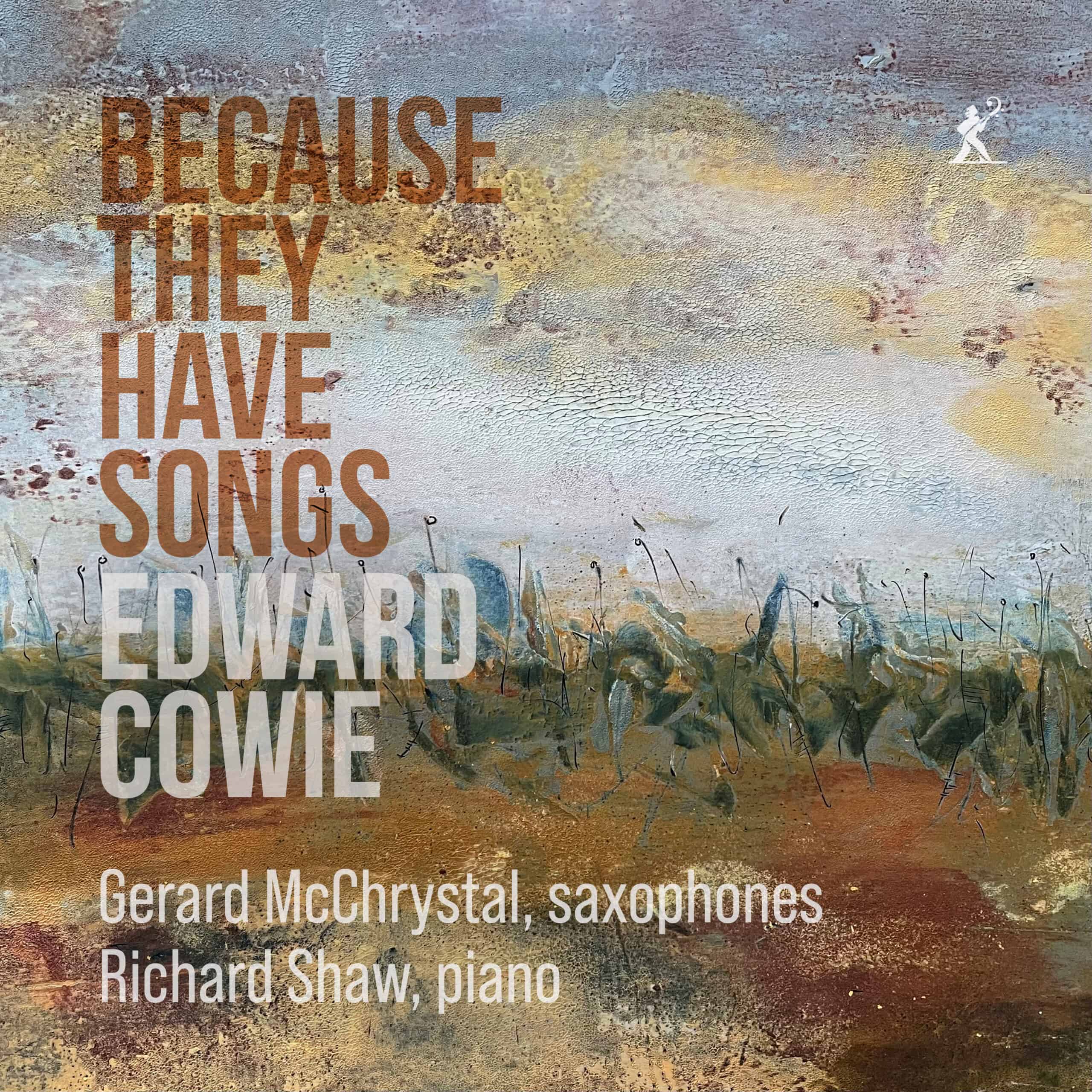

Saxophonist Gerard McChrystal and pianist Richard Shaw give a bewitching performance. It is aided and abetted by a clear, luminous recording.

As with the previous “bird portrait cycles”, Cowie’s liner notes give an excellent introduction to the overall creation, but avoid detailed discussion of movements or pieces. There is also a helpful Afterword which considers the resultant recording and the soloists’ contributions. Of interest are two pages with the performers’ reflections on the music and the project. Resumes of the composer and soloists are included.

The booklet is illustrated with four beautiful examples of Cowie’s pre-composition designs and sketches. There are some snaps of the recording session at the Ayriel Studios in Whitby.

The insert features a remarkable painting of Zulu Ceremony by Heather Cowie, to whom Because They Have Songs is dedicated.

This serenely confident and richly suggestive work is the fourth epic cycle of bird portraits that Edward Cowie has completed in recent years. The preceding cycles were Bird Portraits from 2020/2021 (review), Where Song was Born: 24 Australian Bird Portraits from 2021 (review), and Where the Wood Thrush Forever Sings for clarinet[s] and piano from 2022-2023 (review).

Because They Have Songs is not merely a catalogue of avian caricature, nor a travelogue in sound . It is a deeply personal meditation on the act of listening, of translating transitory encounters with the wild into lasting musical form. Cowie’s approach invites us to hear not just birdsong, but the emotional resonance of place, memory and artistic response. Whether taken in full flight or savoured movement by movement, this cycle rewards the curious ear and the imaginative soul. Like the birds themselves, it sings because it must – because it has songs.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

![🎧 Listen now to the @purcellsingers' first single from their upcoming album, #ASpotlessRose! ➡️ listn.fm/aspotlessrose [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/642752592_1424641949105789_8815810652567824072_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=106&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=aY1NGfNpOoYQ7kNvwGpPQmS&_nc_oc=Adm_ouTe8kvN9RCe61n9mM9b4phV5swbQ4j4hfqj9sxo91DN1QrLsQGoF2AJagHgxt0&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=BAvxXTf_RG0GgOUKCTm42g&_nc_tpa=Q5bMBQF_wqxy5RwyxRc18eIpdIyDjNymVOt9d55VkYc6GK1qtYM_F9emLdhl08Mg-fgaHjGnzDCcvzszGQ&oh=00_Afz4mi7bDwRJN-VbfjAxAB4U15I2t1U9s0DPluE6IDCZMg&oe=69B10701)