Fanfare

Peter Maxwell Davies, the enfant terrible of British music back in the 1970s, has since become an established composer who, like Benjamin Britten before him, has been given a knighthood. Possibly his most famous piece from that era (at least in America) was his bizarre voice-and-instrumental piece Eight Songs for a Mad King, which still has the power to astonish even today (should anyone be foolhardy enough to attempt singing it—it requires a four-and-a-half octave range).

The opening piece on this disc of his chamber music, the Psalm 124 with his own unusual harmonic touches and quiet solo guitar interludes between sections, is far less of an assault on the ear. In fact, it is quite quiet music, gentle and beautifully arranged for flute and alto flute, bass clarinet, glockenspiel, marimba, violin, viola, cello, and guitar. Even the recognizable Maxwell Davies chord positions, though naturally lying outside the original Psalm, are more like a sort of disquieting ambience rather than a tumult of sound. Dove, Star-Folded, composed in 2000 as a memorial for Steven Runciman and “based on a Greek Byzantine hymn” according to the notes, is given to a string trio and maintains the quiet mood, at least at first. In the middle, a busy and rather disquieting fast passage erupts, ebbs, and returns. The annotator remarks on its similarity to the late Beethoven quartets, but it has more in common with the quartets of Bartok.

Economies of Scale had its premiere in 2002, which makes it the latest work on this disc. Here I agree with annotator Christopher Mark that this music does indeed have an affinity with Messiaen, not only because the instrumentation is the same (clarinet, violin, cello, and piano) but also because of certain moments in the chordal writing for piano. This begins as a generally faster, louder, more aggressive piece, and like Mark I find similarities to the Messiaen quartet in the quirky asymmetrical meters. Nevertheless, Maxwell Davies is constantly changing his thematic material, more often in contrast rather than development, possibly because this is, after all, only a one-movement work lasting a little more than seven minutes. Some of the kind of writing one hears for the instrumental ensemble in Eight Songs is present here, the glissando cello passages and the brittle, atonal piano chords that seem to come out of nowhere, but again, the material is condensed and used in what I feel is a more coherent and less shocking (in the emotional as well as the musical sense) progression. It is curious that despite the aggressive opening, the music gradually slows down and almost fades out at the end.

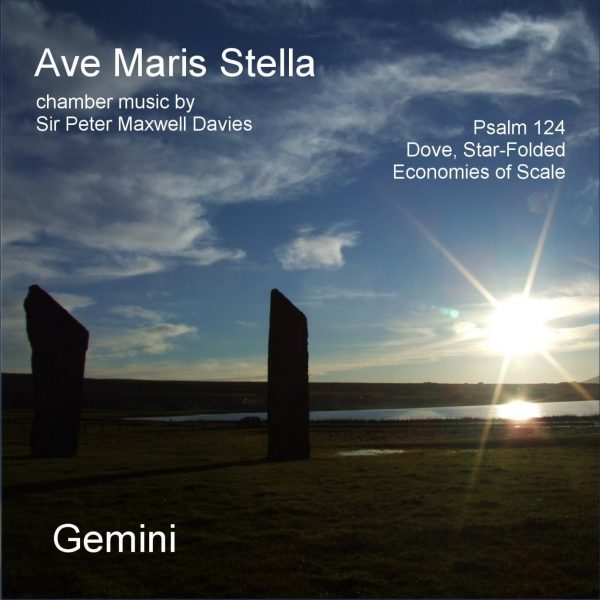

After this we come to the most extended work on this disc, Ave Maris Stella, which was also composed in 1975. It was dedicated to the memory of Hans Juda, who acted as honorary treasurer for the group it was written for, The Fires of London, which by coincidence played the backup for Julius Eastman on that long-ago recording of Eight Songs for a Mad King. It is composed for almost the same configuration as Psalm 124, except that the viola player does not double on violin and there is no guitar. The theme as stated in the opening movement is then transformed in each one succeeding. The notes say that “the main line is not always immediately obvious,” but I find it fairly easy to discern. Your experience may vary. One reason some listeners may have trouble picking up the theme is that it is sometimes broken up and tossed around between the instruments, almost hocket-style, but if you’ve heard as much jazz as I have where exactly the same thing happens (believe it or not, this goes back as far as the New Orleans style played in the 1920s as for modern jazz), you’ll hear it. Like the instrumental ensemble used on Eight Songs, the music here is decidedly more nervous in places, even grating. Maxwell Davies’s sense of structure keeps the piece from becoming incoherent, but particularly because of the edgy, harsh sound he requires of the clarinetist, I find it a little too edgy at times. Nevertheless, the composer creates some remarkable and fascinating instrumental blends, particularly in the marimba passages, which sometimes well up from below like a harp, and at other times assert a cross-rhythm that sets the whole ensemble a little more on edge and takes it farther away from a comfort zone. But as Duke Ellington said in the early 1960s, when he was asked to play in an “avant-garde” style, “Let’s not go back that far!” The extended marimba solo in variation 6 reminds me of some of the work Red Norvo did back in the 1930s, particularly his 1933 recording of Dane of the Octopus where he played marimba instead of his usual xylophone, although Maxwell Davies develops the music more thoroughly and, toward the end, the viola plays a soft yet edgy sustained note in the background that eventually leads us to busier, more aggressive music once again. Yet the trend toward quietude is stronger, and the work ends with a variation where the marimba plays repeated notes on the beat while the strings sustain different tones, before eventually moving upward (possibly an allegory for a soul striving toward heaven?), the instruments play a crescendo, and the work ends disquietingly. Years of experience of listening to modern music has, for me, finally taken it away from the province of the novel and helped me hear it more in context for its thematic development and placement within the long continuum of musical creation. Perhaps, also, hearing later music that is far stranger than Maxwell Davies’s has taken some of the edge off his “avant-garde” label. You might put it that his music is more purely enjoyable to me now than it once was, and the generally quiet (one might almost say subdued) mood of this recital draws listeners inward rather than pushing them away.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978