Audio-Video Club of Atlanta

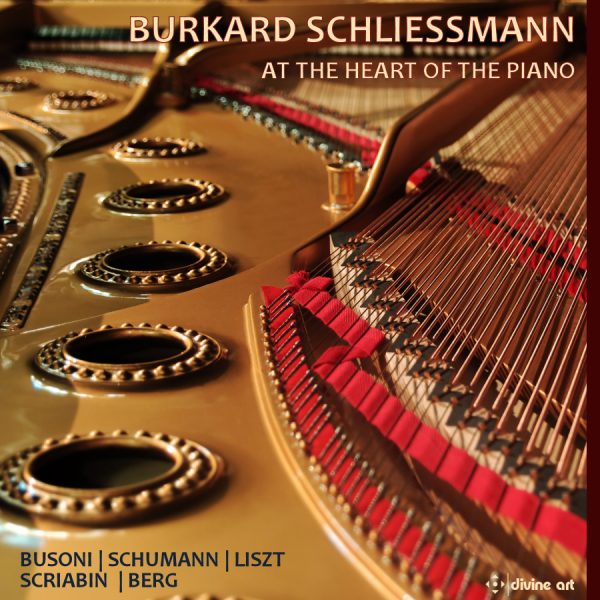

“At the Heart of the Piano” is a 3-CD collection of dynamite recordings by Burkard Schliessman that really define him in terms of his distinctive profile as a pianist. The native of Aschafffenburg Germany has often been noted for his passion for using all the resouces of the instrument to get to the heart of the music and bring it out in all its expressive power and beauty. In that respect, he reminds me of the fondly remembered American pianist Earl Wild (1915-2010), especially in his accounts of the Romantics.

Speaking of which, his Schumann recordings call for special recognition. As I said of Schliessmann in a review some years ago, “he is the last sort of pianist you would expect to just play the notes as written, without comment.” The composer would certainly have approved. In his account of the Symphonic Etudes, which Schumann described as “etudes in the form of variations,” Schliessmann incorporates the five “posthumous etudes” that Brahms published after the composer’s death, carefully distributing them for best effect to fill out the harmony. That is no easy task, but carefully placed, these etudes add much in the way of searching, introspection, and exaltation to a work that is already distinguished for its wealth of color and for Schumann’s notable mastery in blending, contrasting, and superimposing timbres. Schliessmann takes all these issues in stride, making this an eminently satisfying account of one of the most difficult works in the repertoire.

He also does a fantastic job in Schumann’s Fantasia in C Major, Op. 17, a work marked by rhapsodic lyricism occasioned by trill structures, which are typically in downward motion, in the opening movement. It is succeeded by a march in the middle movement that culminates in sensational back-rhythms and syncopations that still have the power to astonish us today, and a finale whose harmonic structure conjures up the image of a star-filled night of which Schumann was doubtless thinking when he subtitled this movement “Crown of Stars.” The reader will note how the composer reversed the usual order of this slow movement, marked “thoroughly fantastic and sorrowfully laden” (Durchaus fantastisch und leidenschaftlich vorzutragen) and what then became the middle movement with its thumping fortes in the afore-mentioned march.

There follows Franz Liszt’s wonderful Sonata in B Minor, in which the dramatic tensions, and releases of the same, are in part a direct function of an unusual structure in which all the elements of sonata-allegro form (exposition, development, lead back, and recapitulation) are encompassed by a single movement, played continuously. Any pianist less knowledgeable than Burkard Schliessmann might easily end in disaster in a work that has also been unified by a considerable application of cyclical form, making it imperative to think ahead to where you are going. Carefully considered pauses, allowing the music room to breathe, powerful climaxes, hard-won struggle, and then a devotional atmosphere based on high, bright harp-like chords, and then a radiant conclusion sinking softly into near-inaudibility: all these and more contribute to the effectiveness of the B Minor Sonata in an informed interpretation. Schliessmann’s is one of the best, an inspiring triumph of faith and art.

The program actually begins with J S Bach’s famous Chaconne from Violin Partita No. 2 in the piano transcription by Ferruccio Busoni which is the first track on CD1. In retrospect, it seems as much of a work of Busoni as it is of Bach. Certainly, the changes of tonal color, dynamics, and increasingly dense harmonic effects are more easily accomplished and more effective than they would have been on the harpsichords available to Bach, as is Busoni’s extensive use of the pedal. On the other hand, Schliessmann has to work harder to achieve its demon pacing and high-energy rhythms on his modern Steinway D. The moments of calm and reflection that accompany heart-stopping key changes at about 7:10 and 10:55 in this performance have all the effect anyone might desire.

CD3 is dedicated solely to two composers whose work was absorbed in speculations about the future of music, Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) and Alban Berg (1885-1935). They could not have been more different. Scriabin, the Russian, showed only the most casual reverence for received musical tradition. He was a visionary, in his quest for ever more brilliant tonal expression as well as in his own spiritual orientation, based on the Theosophy of Madame Blavatsky but going beyond that in his embrace of enraptured musical tones. His Sonata No. 1 in F-sharp minor, Op. 23, represents an early breakthrough, particularly in his choice of an extraordinarily rich and difficult key with no fewer than six sharps in its signature. The work has the requisite four movements of a classical sonata, to which it pays homage, but clearly Scriabin is interested in something other than thematic development. The final movement, Presto con fuoco, ends suddenly without a decisive finish, as if Scriabin had finished digging all the brilliantly colored musical ore in this particular mineshaft.

It would be easy to dismiss so many of this composer’s musical explorations as mere incontinent rhapsodizing (as some observers have continued to do to this day), but that would be to miss the point of what this composer was all about. In a 66-minute selection including Preludes, Etudes and Dances, Schliessmann presents Scriabin as a man on a quest for transcendently beautiful tonal expression in large forms as well as small. Using chains of thirds and transposable fourths, he created musical structures of great beauty. In the process, he also showed other composers what could be done with rich and rare keys they had generally avoided, such as G-flat major (six flats) and E-flat minor, also six flats. (Its enharmonic parallel is a more accessible F-sharp major). All this he did in the interest of music expression that might be darkly glowing, melancholy or ecstatic.

Someone like Scriabin is obviously a hard act to follow. So, what are we to say of the Austrian composer Alban Berg, whose 11-minute Piano Sonata, Op. 1, concludes the program? At the opening, flickering shy lights take the place of the dramatically compelling or quietly understated introduction we might have expected. As in the Liszt sonata, all the structural elements are subsumed in a single movement, but the thrust is quite different. We have here music that is still basically tonal, leading to musical structures in which melody and harmony are subjected to constant variation and interweaving. In Schliessmann’s sensitive performance, I found a down-to-earth warmth of human emotion that I had not expected to discover in a composer who was to be associated with the 12-tone music of the New Viennese School. For yours truly, that was a nice revelation.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978