The Chronicle Review Corner

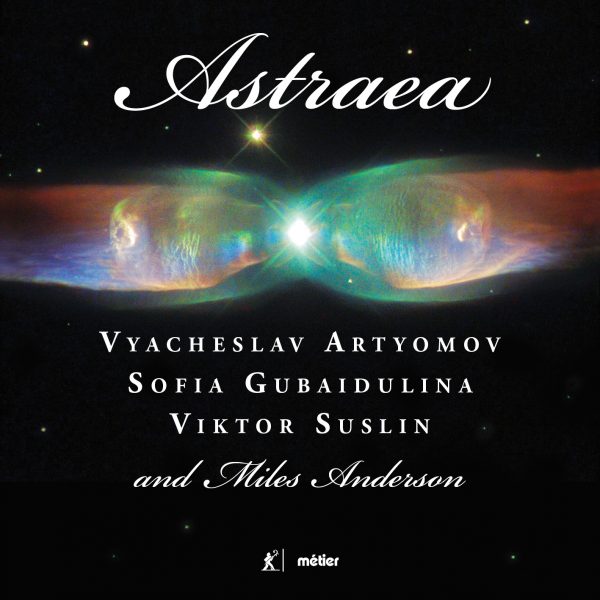

Sometimes with a bland pop album, one might call it “inoffensive”; the music is fine but unchallenging. With this album of archive experimental recordings, “not at all unpleasant” would seem to be a decent review, given the circumstances of its recording. It’s worth remembering that at the same time as the Astraea Ensemble was in operation, over in the UK, young people who’d never before picked up a guitar were forming bands and playing punk, in an attempt to overthrow the tedious dominance of prog rock and other stultified forms of music.

The Astraea Ensemble are as listenable as some of the punk music around then (and certainly better than anything The Damned ever put out). Fans of the likes of Captain Beefheart and Pere Ubu and the more out-there moments of Hawkwind will find some of this familiar. The members of the ensemble were also punkier than the punks, rebelling as they were against a totalitarian regime. All three Russians were members of Khrennikov’s Seven, a group of seven composers denounced at the sixth congress of the Composers’ Union for unapproved participation in festivals of Soviet music in the West. Khrennikov called their music “pointlessness … and noisy mud instead of real musical innovation”. The composers subsequently suffered restrictions on performance and publication of their music. The worst punks ever had to face was tabloid outrage.

As for the music, in the sleeve notes, Artyomov explains: “At first, we improvised on the basis of the schematic compositions created by each participant, which reflected the individual intentions of the composers who wrote them. However, soon we discovered new possibilities within ourselves, ceased being simply ‘performers,’ but concentrated exclusively on spontaneous, previously unprepared improvisation, which requires maximal concentration, inner freedom and self-oblivion. Performances in front of the public violated these conditions, demanded ‘performance,’ and not creation, and it was necessary to relinquish that in favour of studio recordings. We recorded in ‘one breath’ so to speak, a number of rather lengthy musical compositions, which turned out to be so varied in their expression and endowed with such natural logic of the motion and change of character, that even our colleagues could scarcely believe in the achievement of such unity without rehearsals or montage. This was a special, most unvarnished and sincere of all of the well-known types of improvisation, most likely, comprehensible only to composers, moreover, those who have passed through special inner adjustment. In reality, this was not a creation of form by means of sounds, but the manifestation of the inner life of each of the participant in the sound.”

So, if we have it right, it’s three people playing whatever comes into their heads with no real attempt to link it with what the other two are playing, while someone leaves a tape running. As said at the start, it’s remarkable it even works. Instruments used include the duduk (Armenian reed woodwind), the salamuri (Georgian, recorder), the tar (Iranian lute), the kiamancha (Iranian bowed string instrument), chonguri (Georgian cello type instrument), the kanon (Arabic harp type thing), the mandolin, various types of drums, and bells. There are two pieces using those instruments, recorded by the ensemble in 1977 and 1980, while the third piece is quasi-electronic and also an improvisation, with a very small amount of set arrangement. The end result is not difficult — there’s nothing that brings to mind fingernails and blackboards — but neither is it replete with melody and harmony. In as much as there is any pattern, the opening piece Archipelagos of Sounds in the Ocean of Time is more percussive. It’s got a slight air of mysticism: add a beat and it might be music for a religious dance, while with added synth it might be ambient music for meditation. The closing Death Valley is part electronic and more ambient. The middle piece, Dolcissimo, is more Gong/Hawkwind in feel (without drums, guitars etc), the sort of sound where Michael Moorcock might be wheeled out for a poem midway through a Hawkwind set. Dolcissimo is perhaps the closest it gets to conventional. The various instruments give it an eastern feel in places, but no more than a feel. Not for everyone but interesting nonetheless.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978