Fanfare

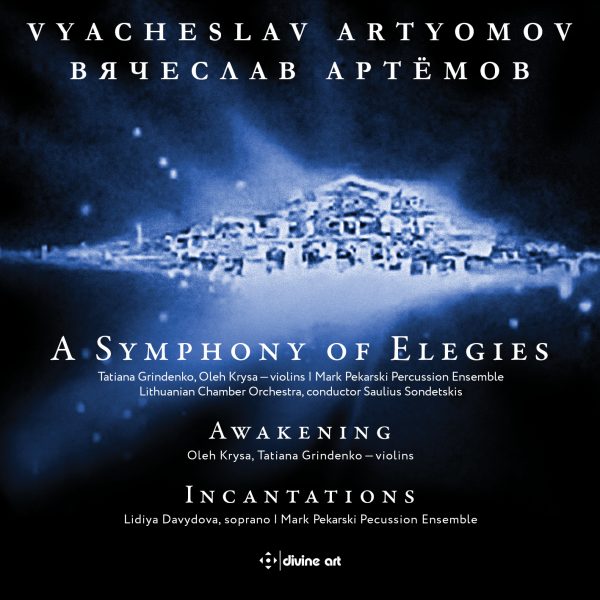

As with earlier Divine Art releases devoted to Vyacheslav Artyomov’s music, these are not new recordings, but rather reissues of recordings that Melodiya made in the 1980s and 1990s. Some of these appeared outside of the Soviet Union on the Olympia CD label, so check your shelves before pulling out your credit card. Furthermore, just to make things confusing, Incantations was previously issued under the title Invocations; the music (and the recording) are the same.

I have written positively about this composer’s music as recently as Fanfare 42:2. I find this release even more consistently interesting than the two that I reviewed in that recent issue because the music is on a consistently high level and is more focused. A Symphony of Elegies, the composer’s first symphony, was composed in 1977 while he was visiting Armenia. The title should be taken literally; there are three movements, titled Elegy I, Elegy II, and Elegy III. Elegy I starts with a dark, slowly roiling cloud of strings from which individual violins gradually free themselves. Ligeti’s micropolyphonic writing for orchestra or string ensembles seems to have been an influence. Elegy II continues the process, and gives the two solo violins greater prominence, separating them more clearly from the orchestral textures. Pale, washed-out colors and slow glissandos also suggest the music of Gloria Coates. Then, in Elegy III, which is the longest movement (20:40), percussion instruments come into the foreground. Even more slowly than in the previous movements, the colors and textures evolve, and the two violins seem to be swallowed up by the sun, which leads to a long disassembly of the structures that Artyomov had been building not just in this movement but also in the entire work. Despite being over 43 minutes long and essentially slow throughout, A Symphony of Elegies is intense and gripping, and it is played with understanding by these musicians.

The composer calls Awakening, composed a year later, “almost… a postlude” to the symphony. Now the two violins are by themselves and, at the start, seemingly in a state of suspended animation. Over the course of 11 minutes, they awaken and stretch their arms out toward new consciousness. Although the title could be taken literally, the awakening that the composer was thinking of appears to be of the metaphysical kind. Within small note intervals, the violins do a lot of sliding around, and again, the pale colors and slowly melting textures suggest Gloria Coates’s music. One imagines that this was considered to be beyond outré when it was presented to Soviet audiences in the very late 1970s. The performers here also were the original performers, and I am not sure how anyone could make a better case for this odd music.

Incantations is weird too, but in a different way. There are four movements: “Incantation of Fate—Of Serpents,” “Incantation of Stars—Of Birds,” “Incantation of Souls—Of Wind,” and “Incantation of Sounds—Of Fire.” The soprano has no text per se. Instead, sometimes as a chant and at other times as a coloratura roulade, she sings nonsense or onomatopoeic phonemes, rolling her “r”s and blowing raspberries to beat the band. The last of the four movements is the most active. Soprano Lydia Davydova comes off as a Russian Cathy Berberian, and I mean that as high praise indeed. When she isn’t channeling Cathy, she seems to singing an alternate version of Messiaen’s Harawi, or something by George Crumb, and I mean that as high praise too. The percussionists play a variety of instruments, both pitched and unpitched, and sometimes they get into the act vocally. Again, the music is slow but not dull. Listening to this, you might feel that you are on a National Geographic expedition and, in the middle of a clearing, have found the last surviving member of a tribe previously known to civilization. Schnittke called the work “a strikingly realistic and vivid sound image of primeval magic,” and that description strikes me as perceptive. Peter J. Rabinowitz reviewed this particular recording all the way back in Fanfare 12:2, and he was beyond being underwhelmed by it. No criticism of Peter implied, but this work, and this performance of it, both work for me.

This is pretty wild stuff, but Artyomov’s sincerity is not in doubt, and this recording could be a good place to start, if you are curious about him.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978