Fanfare

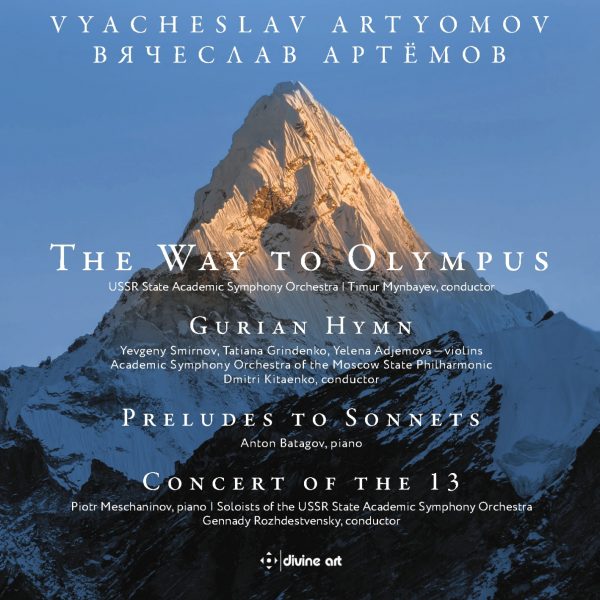

JOINT REVIEW OF DDA 25164 and DDA 25171.

Divine Art is doing composer Vyacheslav Artyomov and his admirers (among whom I include myself) a service not only by producing new recordings of previously unrecorded works, but also by releasing older Soviet recordings that have been difficult or expensive to find. I’ve spent more than I usually spend on a CD or LP to fill gaps in my Artyomov collection, and I am glad that other collectors, at least, are going to benefit from Divine Art’s thoroughness and thoughtfulness.

The works on the first CD were recorded by Melodiya between 1977 and 1990, and the sound is fine. The major work here is the one-movement, 33-minute symphony The Way to Olympus, com¬posed in the late 1970s but later revised. It is the first part of a four-symphony “Symphony of the Way” tetralogy whose other works are On the Threshold of a Bright World, Gentle Emanation (both already released by Divine Art in new recordings), and The Morning Star Arises (as yet unrecorded, I think). The composer writes that the four symphonies present different stages in the spiritual progress of the symphony’s hero. In other words, this is a massive Heldenleben. Dedicated to his wife, the poetess Valeriya Lyubetskaya, the present symphony (in Artyomov’s words) “conveys the idea of overcoming inertness and passivity for the sake of movement, an aspiration for perfection, for finding integrity in one’s inner development.” When this very same recording appeared in the Jurassic year of 1988, Peter J. Rabinowitz (Fanfare 12:2) concluded that, “despite its brilliance, you may find that [the Symphony’s] Respighian hollowness of gesture, coupled with the overstretching of its limited material, eventually snaps your patience.” I think his response is valid, even if I do not share it. To me, the symphony sounds like an extended fever dream influenced by Scriabin—but by a Scriabin who knew Ligeti’s music. I mean the composer and the music no disrespect—I don’t doubt the seriousness of his intentions—when I say that this is pretty trippy stuff. Light some incense and have a good time with it, I say.

Rabinowitz liked the Gurian Hymn much better. Written in 1986 and also dedicated to Lyubetskaya, it also presents a hero—here, a trio of solo violins. The violins are “confronted with the faceless mass of the string orchestra,” but supported, both literally and figuratively, by a Georgian Easter song, which is used like a cantus firmus. This is a less diffuse score, reminiscent of the spiritual Minimalism practiced by composers such as Kancheli and Part. I also hear hints of Ives’s The Unanswered Question in this work.

Piano music is not prominent in Artyomov’s canon; the three Preludes to Sonnets (1981), in fact, are the sole entry. The sonnets in question are Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus, and the preludes are between two and almost five minutes in length. Again, these are more concentrated scores, thoughtful in mood, and something like early Messiaen in how they use the piano.

Concert of the 13 (1967) refers to the number of musicians involved. The composer calls it “a sort of game, a show in which the thirteen musicians compete with and complement one another in various combinations and groupings.” There are four brief movements. The writing is imaginative, and the mood is alert, questioning, and sometimes humorous (a surprise for this composer). I don’t think Artyomov had found his individual voice in his Concert, yet there’s a maturity and control here that must appeal to other musicians. (It has been recorded three times.)

Most of the second disc is devoted to Sola fide (Only by Faith), a ballet based on Aleksey Tolstoy’s The Road to Calvary. (It’s a trilogy of novels dealing with the fate of the Russian intelligentsia around the time of the Russian Revolution. Intrigued, I checked to see if they were translated into English, and the answer is yes, but the books are out of print.) The concept dates from the early 1980s, although Artyomov did not complete Sola fide until 2016. He calls it a “ballet-requiem,” and it actually overlaps, in 10 of its 30 sections, with the Requiem Mass that he composed between 1984 and 1988. (Both works are dedicated to “the martyrs of long-suffering Russia.” To add to the confusion, the first three sections of the ballet comprise a third work, which goes under the name Lamentations.) Thus, five of the 12 movements presented here include a chorus or soloists singing Latin texts, although the movements themselves have titles such as “Separation” and “Wind, wind.” The Requiem was my first exposure to this composer, when I reviewed it here in 2006. It impressed me and bothered others, probably for similar reasons. (Penderecki’s name keeps coming up, although to be fair to Artyomov, he is more eclectic than that—choral glissandos and keening figures in strings alone do not constitute an imitation of the Polish composer.) It appears that the composer has prepared at least four suites from the ballet; the third (“Katia”) and fourth (“The Terrible Days”), each in six movements, are the ones that have been recorded here. The music is not balletic, at least not in a traditional sense. Like the Requiem that it intersects, the music is heavy and doleful—clearly modern, and with an awareness of the avant-garde, even though the avant-garde is not embraced.

The recording was made by Melodiya in 1988. Melodiya’s recording of the Requiem was made, supposedly, in 1989, and it features an almost identical list of performers. I am not at all sure that the overlapping movements (here, “Tuba mirum”/”Separation”, “Requiem aetemam”/”Acquistion”, “Domine, Jesu Christe, Rex gloriae”/”Plea”, “Dies irae”/”Wind, wind”, “Lacrimosa”/”Terrible Days”, “In paradisum”/”Finale”) are not the same recordings. The engineering is shallow, yet serviceable, and the performances seem excellent, with no lack of commitment or understanding.

The last 16 minutes of the disc are given to a “concerto for orchestra” from 1976, Tempo Costante. This work “plays with an idea of unchangeable, eternal time,” according to the composer. He was thinking of poems on the subject written by Goethe, Tennyson, and Mairhofer, and these poems may be read during a performance of the music. (Here, they are not.) Musically, the concept is that the music only appears to accelerate or decelerate because of decreasing or increasing note values. The underlying pulse remains the same, however. As I recall, this is an idea that Honegger played with in Pacific 231, except Honegger’s idea was to make the music sound faster and faster as its pulse actually slowed. Stylistically, this is not unlike Concert of the 13 on the first CD. There is a stylistic gap between Tempo Costante and The Way to Olympus, even though they are virtually adjacent in the composer’s canon. Did Artyomov reach maturity as a composer on the eve of beginning his “Symphony of the Way” tetralogy? Tempo Costante is the only recording on these two discs not licensed from Melodiya. This recording dates from 1994 and is from “the composer’s archive.” It is at least as well-performed and well-engineered as the other items on these two discs.

Divine Art has promised six “Artyomov Retrospective” CDs in 2018, including one devoted to the aforementioned Requiem. He is an intriguing composer and a mystic, and it will be interesting to see what else is uncovered by these new or newly available recordings. For now, I give these two discs a thumbs-up, although you might want to sample before you buy. (It looks like Divine Art has uploaded content from both onto YouTube.)

Raymond Tuttle

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978