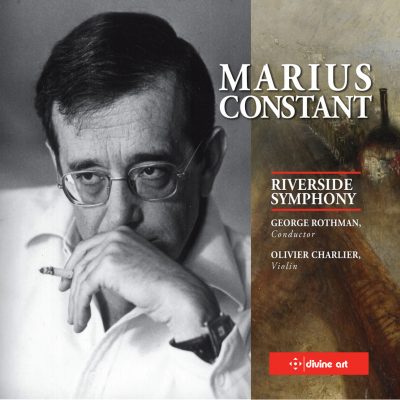

Marius Constant Recordings

7 February 1925 – May 15, 2004

There is a strong case for Marius Constant to be regarded as one of the late 20th-century’s most formidable, though lamentably unsung, composers. A restless, fiercely imaginative artistic spirit, Constant embraced creative challenge—invariably self-imposed—as the natural course of a prodigiously gifted master craftsman driven by an iconoclastic disregard for confining aesthetic doctrine. Though the music can be placed in time, its geographic provenance eludes us, as much for its subtle eclecticism as the powerfully individual harmonic palette into and from which the works coalesce. His music’s sheer beauty and emotional power, revealed through eloquent, deeply engrossing narratives and fresh, otherworldly landscapes, bring the listener face to face with a unique compositional voice.

Constant’s early life in Bucharest suggested nothing of a consuming professional destiny. While a very young man he undertook piano studies, but only in filial duty to his father, a banker and amateur violinist, in Constant’s telling “so poorly skilled that no one else would accompany him.” By age 11, however, Constant was enrolled at the Royal Conservatory of Bucharest in addition to his continuing general studies at the Lycée Français (a French education then de rigueur among the Romanian bourgeoisie). Composing courses soon joined piano at the conservatory, where the young composer quickly advanced.

By age 20, Constant had not only won the prestigious Enesco Prize for composition, but also placed second in a competition for the creation of a new national anthem (Constant later jesting that he would never have left Romania had he captured top honors). Such was not to be, however. Against a backdrop of personal loss—the death of his mother when he was only nine, brutally compounded by a house fire in which his father, sister and stepmother also perished—Constant chose Paris as his new home, moving there with his wife (a dancer) following World War II’s end. Enrolling at the venerable Paris Conservatory, he studied with Olivier Messiaen and Tony Aubin, later undertaking private tuition with Nadia Boulanger and Arthur Honegger.

Constant worked at the Studio d’Essai of Radio-France between 1952 and 1954 before co-founding the radio channel, France-Musique, which he directed through 1966. As Music Director of Roland Petit’s Ballets de Paris for ten years (1956-1966), Constant penned such celebrated ballet scores as Cyrano de Bergerac, Nana, and Paradis Perdu (Paradise Lost), later collaborating with Maurice Béjart to produce Haut Voltage (High Voltage). Constant continued his conducting, both as founder of the Ars Nova new music group and other ensembles, leading performances throughout the world. In 1993, he was awarded the prestigious Olivier Messiaen seat at the Beaux Arts Academy.

It is safe to hazard that Constant’s limited celebrity owes in large measure to his steadfast resistance to the avant garde, a term he particularly disliked due to its telling co-opting of military jargon. Visibly represented in France by Pierre Boulez, the movement’s militant antagonism to those at odds with its particular aesthetic preoccupations was a prevailing force in musical culture throughout Europe. Beginning in the mid-‘50s, through its arrogation of state support for performances, festivals and marketing, it proved a powerful force in the building or thwarting of reputations.

Arthur Honegger famously questioned the need to break down doors when one “can simply open them and walk through,” and much in the way of his teacher, Constant recognized that the challenges of composing a single work superseded the vain and futile pursuit of originality. That said, Constant’s music could by no reasonable measure be viewed as retrogressive. While he openly conscripted the lineage of French composers to his “secret garden,” it was an affinity totally subsumed, transformed, and augmented by a deep and loving familiarity with an enormous spectrum of music on an international scale—by no means limited to the classics—and finally, filtered and shaped by exquisite taste. Forged in the incandescent reaches of Constant’s soulful imagination, this rich amalgam underlies the unique musical language that sparked narratives of consistently riveting power. Indeed, Constant’s embrace of narrative alone, not unlike that of his dear friend Henri Dutilleux, set him (or them) apart from fashion in any respect.

Constant experienced an early success upon Leonard Bernstein’s chance discovery of 24 Préludes pour orchestre (24 Preludes for Orchestra) at the Bésancon festival in 1958, which the renowned conductor later programmed with The New York Philharmonic. However, Constant’s greatest celebrity is not in name but by virtue of the 30 or so seconds of music he jotted down one afternoon in 1956 and submitted to an international contest sponsored by CBS television in search of signature theme for the network’s new television program, The Twilight Zone. This short, dramatic interlude (actually two themes were conjoined to produce the final result) reveals a flair for imagery and keen ear for color emblematic of Constant’s music.