Fanfare

Edward Cowie (b. 1943) is an English composer, painter, and natural scientist. In Because They Have Songs, in one way or another, I see him combining all three of these skills, given his musical “painting” of birds and their song production. Additionally, of the tens of thousands of saxophone works, this almost hour-and-a-half one must rank as (one of) the longest. Its 24 movements range from just under three minutes to a bit more than four. Through the course of the work, saxophonist Gerard McChrystal is required to play on the three highest (with the exception of the seldomly played or written-for soprillo) members of the family, the sopranino, soprano, and alto saxophones.

The present work is actually the fourth in a series of works devoted to birdsong from various regions, the three preceding being scored for solo piano. Seeking to expand his vocabulary of birdsong, the composer and his artist wife traveled to Africa in 2014 on an extended trip through the wilds that took them from South Africa all the way up to Victoria Falls in Zambia and Zimbabwe. Thus it is that the birds heard in the present work are all native to various countries and regions on that continent. Now, many composers, including Janequin (whose Le Chant des Oiseaux surely helped launch the interest of subsequent composers), Vivaldi, Beethoven, Schubert, Janáček, Mahler, Sibelius, Ravel, Arlene Sierra (whose Birds and Insects I reviewed in 49:3), and even yours truly, have depicted birdsong, but most readers will first think of Olivier Messiaen when they consider composers of the avian persuasion. While Cowie himself admits to influence from the French master, he stresses that he was interested in representing their sounds in drawings from the age of five—before he knew anything about musical notation. Further, his approach to mimicking their utterances includes sounds from the habitats of these remarkable creatures. He observes that a representation of a seagull, for instance, loses something without the concomitant “swish” of the ocean waves upon the shore.

Reproduced in the booklet are even some sketches, not only of the birdsongs (with which Cowie had familiarized himself via recordings before his trip) but drawings of the birds themselves and their habitats. The composer also emphasizes that he is not slavishly imitating any of the birds, and clearly these pieces are conceived first and foremost as valid musical statements. In any case, I hear an appealing freedom of expression from the very first work that portrays the white-crested turaco. After a few minutes of freely tonal gestures in both alto saxophone and piano, one hears a series of delightfully convincing squawks in the former. The following presentation of the black-collared barbet switches the instrument to the soprano saxophone, allowing the higher shrieks of this bird to be captured, although most of the piece is rather subdued in both instruments. Cowie draws upon various techniques available to saxophonists such as pitch bends, key clicks, quickly repeated notes and figuration, variety of attack, and so on. A bit of an outlier comes in “Southern Ground-Hornbill,” where the opening eschews the often almost atonal writing of the other pieces in favor a rather thoroughly tonal melody in the saxophone accompanied by drum-like figuration in the piano.

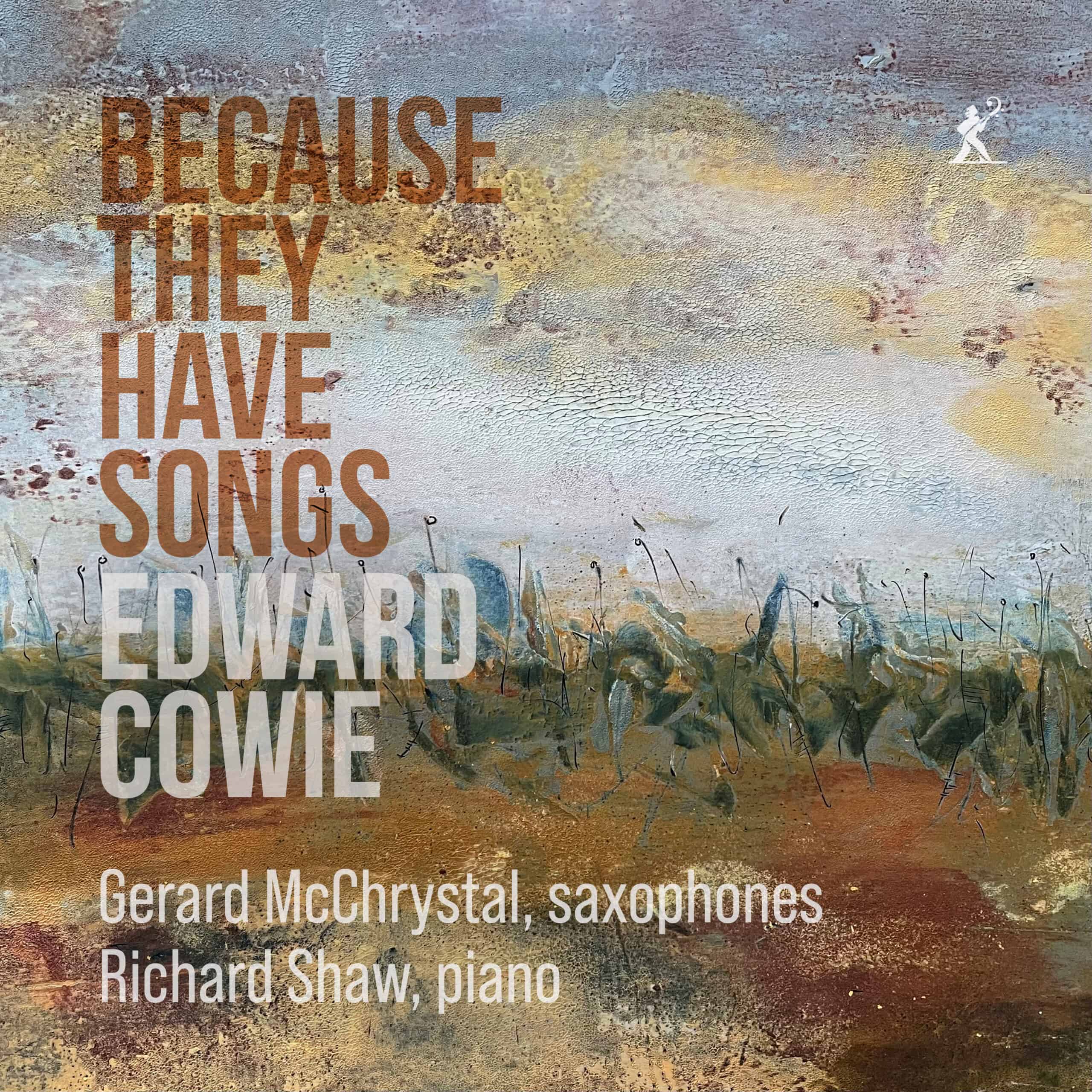

A highlight of the piece for me was the quick gesture of the saxophone in “Kori Bustard” that was followed in echo-like fashion by the same gesture in the piano. Also appealing were the birdlike grunts and squeaks over the range of the saxophone, and the devilishly high runs in “Lesser Striped Swallow,” as well as the elegant harmonies in the piano that support the goings-on in the saxophone. Some humor was brought into the work in “Scarlet-chested Sunbird,” with its raucous descending call in the interval of a perfect fourth, and in the interplay between the two instruments as heard in “Bearded Woodpecker.” In sum, the variety of sounds and effects employed throughout this suite keeps the listener actively engaged. Gerard McChrystal proves himself a master of each of these pieces and the effects in them through his easy fluency of execution, variation of tonal production, and sense of line. Some of the pieces are real finger-busters for both instruments. Pianist Richard Shaw is a gifted collaborator as evidenced by the musical and technical polish that he brings to his part. The ensemble playing in their music-making is most impressive. The composer seems to consider these artists’ performance of this work definitive, as do I.

This CD is not “for the birds” or simply just for their lovers, or even only for admirers of fine saxophone and piano playing, but for music lovers in general who will be rewarded with a recital of imagination and compelling character pieces. Thus it is that the well-recorded two-disc set receives a firm recommendation from this quarter.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

Search

Newsletter

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978